.

[This is an entry to the Adversarial Collaboration Contest by John Buridan and Christian Flanery.]

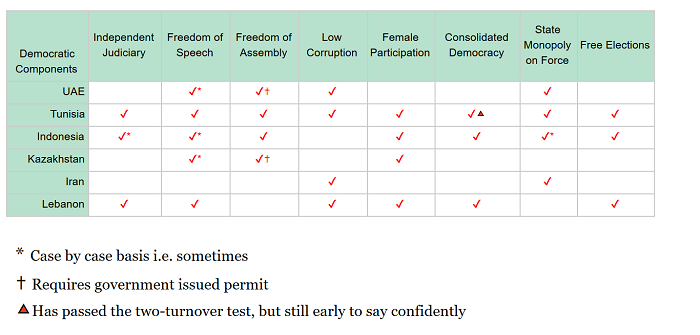

Matter: To what extent does liberalism and democracy obtain in Islamic countries. Whether Islam consistently poses political opposition to liberalism and democracy.

Two simple narratives have split the western world’s perspective on Islam.

These two narratives do not exhaust the spectrum of opinion, but they do function well enough to establish the basic controversy around Islamic countries and Liberal Democracy.

The first narrative opines that Islam is an ideology inimical to “western values,” such as classical liberalism and liberal egalitarianism, and a rival to the Judeo-Christian social mores. It constitutes an ideological rival, inherently aggressive, both unable and unwilling to sustain non-partisan legal systems, democratic norms, fair treatment for opposition parties, protection of dissidents, or the basic rights and freedoms which Western European and Anglophone countries enjoy. And that Islam sustains this undesirable state of affairs.

The second is that Islam is not qualitatively different from any other religion. Islam has contributed to civilization in a significant way, and ordinary Muslims share our own values of family, peace, and justice. In contrast to the first narrative which stresses Islam as an ideology, the second narrative emphasizes that Muslims are normal people. There is no problem with Islam eo ipso; the perceived “problems” of Islam are actually some combination of the fairly normal problems of traditional societies, poor socio-economic conditions, and legacy problems from colonialism.

In order to avoid a point-scoring debate between these two narratives, our approach is to provide a descriptive examination of the performance of liberal democracy within Islamic environments. We take as granted for this paper that one cannot look at a religion on paper and predict what it will look like in a polity. Religious practice and theological doctrine inform every aspect of the pious person’s outlook and life, but the way in which it informs that outlook is not deterministic and cannot be gleaned merely by looking at the source texts, nor by the impossible task of a quantitative comparison of which religion has produced more violence across regions and millenia. Although we believe original texts are not deterministic, that does not mean Islam is totally amorphous. Religious culture is a powerful force within society. It unifies people, allows them to feel part of something bigger and better, it provides solace in their troubles, and can mobilize political action. How that mobilization of power occurs remains largely up to the needs of the moment, but it’s that mobilization of power which we are interested in.

A community’s interpretation of a religious text can be unpredictable, and our study does not hold such texts as a reliable source for predicting political outcomes. Nor will we attempt to determine the nature of Islam by enumerating the good and bad works it has produced. We hold that investigating the politics of a particular community over time more adequately casts light on the possibilities for the future than the foundational texts of the culture.

Our methodology is to investigate the recent political history of Islamic countries as they relate to democratic forms of government and the package of rights we call ‘liberalism.’ We survey the national history, constitutions, and current political environments to determine the extent to which democracy and liberalism have obtained in these countries, and we predict the conditions under which more democratic and liberal policies could emerge. Islam is a useful study since certain well-known expressions of Islam are decidedly neither democratic nor liberal. The “Islamic world” is one of the largest populations groups in the world, and so each Islamic country’s relationship and experimentation with democratic forms of government and human rights is important for the future.

First, we will define our basic terms.

Democracy – A system of government which rejects the rule of a single interest (dictator or oligarchs) through the participation of citizens and some separation of powers.

Liberalism – In an effort to avoid taking sides between classical and egalitarian forms of liberalism, we are just emphasizing the basic liberalism of texts like “The Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen”, “The Declaration of the Rights of Women”, and a generally consistent protection of these rights by the police and judiciary.

Islamic country – for us any country with a Muslim population of 70% or higher. We use the phrase Islamic country even when the country in question is officially nonsectarian. The six countries we study are United Arab Emirates, Tunisia, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Iran, and Lebanon (see the section on Lebanon for more on our reasons for choosing this country). We chose these countries for their geographic range, cultural diversity, and relative stability. These countries can act as a representative sample for future inquiry on politics in Islamic countries.

In each case we examine the history, constitution, and current political environment, focusing on democratic mechanisms and human rights records.

We stress constitutions because they are useful, tangible indicators for political outcomes. However, constitutions can be misleading, and so reviewing the context and results of implementation is essential in making sure our moorings are in the political world and not hypothetical jurisprudence.

United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a sovereign nation state founded in 1971, and composed of the lands of seven Emirates. An Emirate, is the rank, land, or reign of an Emir. Emir is the patriarch of a tribe and the leader of an Emirate. Emir’s are also referred to as Sheikhs at times, which simply means leader of a tribe. The Emirs and their family rule each Emirate and power is passed through male successors. The 1971 unification was the first time the Emirates were united into a formal state. Despite the constraints of the constitution, each Emirate still enjoys a degree of autonomy within the confines of the union.

History

In 1971, the seven gulf emirates unified themselves into one sovereign state known as the United Arab Emirates (UAE). This was in response to the withdrawal of the British Protectorate over their provinces in 1968. The UAE adheres to a long standing cultural tradition rooted in ancient tribal systems. This tribal tradition, and a 500 year old geopolitical strategy of precarious orientation between the Islamic world and western power are the determinants of the UAE’s place in the contemporary international order.

In order to be a citizen of the UAE, one must prove a direct ancestry dating at least as far back as 1930. This dictate resulted from fear in the 1940s that tribal relations would be diluted in the wake of increasing immigration caused by oil discovery. The tribes that compose the UAE are Arab. Some tribes have occupied the strait of Hormuz and Persian gulf coasts since the days of Alexander the Great’s conquests. Others migrated out of the Arabic desert in the 1700s and settled parts of the coast.

Arabic tribal arrangements served the needs of a people in a desolate landscape where living on one’s own meant death. Because resources were scarce, tribes hoarded them jealously and placed a premium on tribal solidarity. This meant discouraging inclusion of outsiders and prohibiting membership in the tribe other than through birth. This mentality has played a role in discouraging the promotion of democratic norms. Citizenship is denied even other Arabs who do not have direct tribal links, and a patriarchal kinship system orders politics, not democracy nor kingship.

The tribes were never formally unified until 1971. Historically, when security concerns arose, they often operated in loose confederation with one another in order to protect mutual interests. In the 16th and 17th centuries the emirates entered agreements with Portugal to protect their trade routes stretching from Swahili in East Africa to India and beyond. These were especially lucrative on account of demand for pearls in Europe. This system was renewed under the British protectorates of the 19th and 20th century. In 1968 the British withdrew their protectorate, prompting the Emirates to form a unified state. The newly created UAE then established security agreements with the U.S. similar to the client relationships they had with the Portuguese and the British.

Today, longstanding squabbles between the Emirates still influence relations. Even at the inception of the UAE, Bahrain and Qatar were originally destined to join the union. On account of old territorial disputes between the emirates, the two decided to establish their own independent states. These long standing conflicts continue to assert themselves as we have seen in the 2017 severing of ties between the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and Qatar.

In addition to tribal disputes, the UAE fear a continually more bold and expansionist Iran. The Emirate’s historical relationships with western powers remain the primary means of securing themselves in an often volatile and unfriendly region. Consequently, the UAE’s close ties with the U.S. constitute a critical security lynchpin if they are to remain autonomous and unharrassed. This necessitates paying some degree of lip service to American values, as we will see below.

Constitution

The UAE constitution was ratified in 1971. It represents a middle of the road effort by the ruling Emirs to cater to western democratic liberalism while retaining as much of their central power as possible under the traditional patriarchal kinship system. As shown in the history section, the UAE clings to its tribal systems and asserts them against efforts to dilute tribal ties. Democratic instruments such as universal suffrage and the power of collective, popularly elected legislative bodies threaten these modes of rule.

In 2004, a number of amendments were made to the constitution. The preamble in this version, stakes out a commitment to a Westphalian1 conception of the state and a commitment to democratic principles and process.

Desiring to create closer links between the Arab Emirates in the form of an independent, sovereign, federal state, capable of protecting its existence and the existence of its members, in cooperation with the sister Arab states and with all other friendly states which are members of the United Nations Organization and members of the family of nations in general; on a basis of mutual respect and reciprocal interests and advantage;…[and] preparing the people of the Union at the same time for a noble and free constitutional life, progressing by steps towards a comprehensive, representative, democratic regime in an Islamic and Arab society free from fear and anxiety;

In the latter half of the 20th century, it became critical that a nation obtain for itself a seat within international institutions. The most common avenue to prosperity and security for emerging states today is through the United Nations and the Bretton Woods Institutions. Access to these international institutions require formal statehood and are not bilateral in nature. Therefore, membership comes with a greater set of demands and requirements. The U.N., World Bank, and IMF are institutions largely oriented at the discretion of western nations and insist on democratic liberalism. The commitments to liberal democracy instantiated in the UAE constitution, as quoted above, serve to keep the UAE in good standing within the international community, maintain access to key international financial and monetary instruments, and facilitate security relationships. There is little substantiating evidence that the Emirates intended to adhere to these commitments to liberal democracy lest their international ties are threatened. This strategy is protected in the constitutional preamble where it states that movement towards a democratic order is, “progressing by steps.” It is not democratic yet but the implication is that it will be eventually. By stating that the UAE will move incrementally towards democracy, the Emirs can justify perpetuating oligarchical rule.

The constitution does contain a number of liberal protections and commitments. It contains non-discrimination clauses regarding race, nationality, religious belief, and social position, but there are no clauses for gender or sexual orientation. It also guarantees free speech, but as we will see below governmental protection of free speech has been dubious according to U.S. reporting agencies.

The arrangement and structure of government bodies provide minimal checks on arbitrary decision making on the part of the Supreme Council which is the highest authoritative body, composed of the seven Emirs. The Supreme Council selects judges and does not require confirmation of its picks by the legislative branch. They unilaterally select the president from their own ranks. The Council of Ministers and its chairman are selected from the population by the Supreme Council. No confirmation is required. The only semblance of popular election based self rule lies in the Union National Council, an advisoral legislative body which is composed of 40 legislators. 20 of them are popularly elected, and 20 are chosen directly by the Supreme Council.

The Cabinet of Ministers submit draft legislation which passes through the Union National Council and then to the Supreme Council for ratification. The legislative power of the Union National council is advisoral only. The Supreme Council can ratify any draft legislation without the approval of any other body or individual. Only the seven Emirs may challenge the constitutionality of laws, which is then determined by judges who the Supreme Council selects. Only the Emirs may submit amendments to the constitution, which require two thirds (30 out of 40, 20 of whom are chosen by the emirates) support in the Union National Council.

Frequently, the constitution reiterates that all bodies and individuals must be beholden to the constitution as the ultimate authority. Shariah is mentioned only once but does exercise considerable authority over the primarily Muslim population.

The preamble commits to democratic rule and the constitution as the foundational binding document, but in effect, it is only a reformulation of pre-existing tribal systems. It masquerades as an effort to create a fair and balanced system of governance, but in reality, it enshrines almost all executive, legislative, and judicial power in the hands of the seven Emirs. This document cannot be considered democratic because it establishes almost no democratic mechanisms, and it lacks important key guarantees, such as gender discrimination and due process, in order to be considered liberal.

Democratic Institutions and Human Rights

Citizenship and Voting

The Emirs select who is allowed to vote and the criteria for selections is not clear or published. It seems a very small number of citizens are allowed to vote. Perhaps 10% of the population of 5 million. In 2015 voter turnout was 35.29% of those eligible to vote. Roughly 11% of the resident population are citizens and 85% of these are Sunni Muslims. In 2010, Pew Research estimated that 76.95 of the total population were Muslim. Obtaining citizenship, and thereby voting rights, requires proving direct tribal lineage prior to 1930. Thus, democratic participation is accessible to a narrow sliver of society. Citizens who do vote, can only vote for a consultative counsel that is not vested with any real legislative power. Some of the Emirates have at times created parliaments with real legislative power but still retain the right to dissolve these at will, which they have.

Constitutional Adherence

The U.S. State Department has reported on the UAE’s many unconstitutional activities. For further reading on these, see the U.S. State Department’s Country Reports on Human Rights Practices and International Religious Freedom Reports.

Article 26 of the constitution forbids torture. Article 30 ensures freedom of expression. Article 28 lays out juridical procedures to ensure defendants receive a public and fair trial.

In the State Department Human Rights Report for 2017, it notes that U.N. human rights experts working with former detainees in the UAE have repeatedly reported the use of torture techniques such as forced standing, threats to rape or kill, and electrocution. Shariah courts also impose flogging for pre-marital sex, defamation, and consuming alcohol.

Activists have alleged that authorities detained citizen Ghanem Abdullah Matar after he posted a series of videos on social media in June that expressed sympathy with Qatar, with whom the UAE are in a bitter dispute over an email hacking scandal. Ghanem, in the video here, criticises the UAE for it’s hard stance on Qatar and for not remembering Qatar’s aid in the conflict in Yemen.

Fair public trials have also been withheld from individuals considered to be potential terrorists or who criticize government policy. The location and status of political activist Nassir bin Ghaith remains unknown from the time of his arrest in August 2015 until April 2016,

“when prosecutors formally announced charges of defaming a foreign country (Egypt), criticizing the UAE’s decision to grant land for a Hindu temple, and having ties to Islamist group al-Islah. In December 2016 bin Ghaith’s case was transferred from the State Security chamber of the Federal Supreme Court to the Federal Court of Appeal. In March authorities sentenced bin Ghaith to 10 years in prison for promoting “false information in order to harm the reputation and stature of the state and one of its institutions.” Bin Ghaith called into question the fairness of his trial, noting an Egyptian judge was assigned to adjudicate a case that involved charges of bin Ghaith defaming Egyptian figures.”

Nassir bin Ghaith did not receive a fair, public trial. The State Department a number of other such cases which strongly indicate that public criticism of the government is likely to result in arbitrary imprisonment.

These are just three areas where the unconstitutionality of acts are disregarded in the name of expediency, national security concerns, or as a relinquishing of authority to shariah courts. The Emirs, despite the existence of binding constitutional law, can still act unilaterally and arbitrarily, regardless of the rights of their citizens or of foreign nationals in the country.

UAE’s Future

Change in the UAE looks highly unlikely in the near future. It was untouched by the Arab Spring, and long standing patriarchal systems are firmly in place. I should note, that while the “incremental” approach to democracy that the Emirs articulate is certainly suspect, (See Cleveland and Bunton’s A History of the Modern Middle East in suggested reading for a good examination of Britain;s use of the same method of maintaining unilateral rule and suppressing democracy in its colonial holdings in Egypt) conditions have improved for religious freedom and female freedom in the UAE over the last 50 years relative to before the unification.

Until the Emirs are stripped of some of their religious and political power it is unlikely things will change any faster than the current snail speed. The UAE is wealthy and its stability is of critical geo-strategic importance to U.S. and western regional concerns who are loathe to demand too much of the Emirs in regards to political change.

In order for the patriarchal system to be supplanted, citizenship would have to be radically expanded, and real legislative power delegated to the Union National Council. As it stands, the Union National Council can tentatively maintain current conditions from worsening, but it is unlikely that it can alter the existing governmental mechanisms in any significant way.

Tunisia

History

After the fall of Rome, the region of modern day Tunisia was sporadically conquered and settled by European tribes until the Muslim conquest of the 7th century transformed the culture and population of the region. It become a province of the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century

In 1881, Tunisia was wrested from the hands of the declining Ottoman Turkish empire and became a French protectorate. In 1956, Tunisia declared independence, adopting a constitution akin to France’s highly centralized presidential system.

This planted the seeds for Tunisia’s becoming one of the few Arab Spring successes in 2011. Tunisian presidents previously could extend their time in office indefinitely. Between 1956 and 2011 there were two presidents. Thus, in the intervening years between independence and the 2011 Arab Spring, Tunisia was an authoritarian presidential system with few functioning democratic mechanisms. Opposition parties were banned until 1981 and even then had little or no influence over the reigning party.

Despite this, Tunisia was relatively progressive under its two presidents, Bourguiba and Ben Ali. Bourguiba focused on the status of women and social and economic development and education. Ben Ali continued this and made some constitutional changes (something separation of powers should prohibit, but on the other hand he did it in the name of fomenting greater democratic participation) that included allowing opposition political parties, and presidential term limits.

Consequently, Tunisia entered the 21st century with greater literacy rates and social safety nets than its neighbors, Algeria and Libya, and many of its peers in the post colonial, Muslim world. While it was socially egalitarian, it was still not democratic. Ben Ali later re-imposed the ban on opposition parties and in conjunction with secret police forces, suppressed political dissent whenever his party became threatened. Cue the Arab Spring, which in Tunisia was known as the Jasmine Revolution, or as The Revolution for Freedom and Dignity. Political corruption, media and internet censorship, and high unemployment continued to mount in the 21st century and precipitated a waning of public faith in Ben Ali, that turned into protests in 2011 which the government suppressed violently. Eventually, Ben Ali was forced out and a new struggle emerged between secular and Islamist groups. A moderate Islamist group, Nahdah, functioned as the moderator between secular minded groups demanding a democratic and liberal regime like Ben Ali’s and hardline Islamists pushing for a government founded on Sharia principles.

After a series of negotiated compromises, a new constitution was drafted in 2014 that intended to resolve and balance liberal concerns, and the role of Islamic Shariah within the newly established Tunisian state.

The 2014 elections were a resounding victory for the secular Nidaa Tounes coalition who won 85 of 217 seats compared to the moderate Islamist Nahda party who won 69. This was a critical consolidating juncture for Tunisia’s nascent democracy. The world held its breath waiting to see if the Islamists would concede and legitimize the elections. When Nahda conceded and no challenge came against the results, Tunisia’s democracy became consolidated. This is critical sign of how robust the democratic regime is as Nahda still has significant sway and influence and continues to cooperate and work within a democratic framework and does not challenge mechanical pillars like election results, and universal suffrage. It is a powerful nod to Islam’s potential to interface with liberal democratic systems. Since 2014, Nidaa Tounes has consolidated more control over parliament and this correlates with increased radicalization amongst Tunisian citizens as the government appears more and more to be unfaithful to the country’s Islamic heritage.

As we saw with the UAE, Tunisia’s leaders, before and after the Jasmine Revolution, saw close relations with Western partners, in this case France and the U.S., as critical for their continued independence and success. Unlike the UAE, the commitments to liberal democracy promulgated in the constitution are manifested faithfully and are reflected in the 2014 election results. As we will see next, the Tunisian constitution commits to the American constitutional model and even corrects what many political scientists see as deficient in the American model.

Constitution

Tunisia’s 2014 constitution is strongly nationalist and Muslim. It asserts Tunisia’s independence as a sovereign national state, and also as an integral member of the Arab Maghreb of North West Africa. It’s religion is Islam, as stated in article one, and the people see themselves as part of the Islamic world.

The preamble lays out quite clearly the intent and values of the new government:

“With a view to building a republican, democratic and participatory system, in the framework of a civil state founded on the sovereignty of the people, exercised through the peaceful alternation of power through free elections, and on the principle of the separation and balance of powers, which guarantees the freedom of association in conformity with the principles of pluralism, an impartial administration, and good governance, which are the foundations of political competition, where the state guarantees the supremacy of the law and the respect for freedoms and human rights, the independence of the judiciary, the equality of rights and duties between all citizens, male and female, and equality between all regions,”

Here is a link to a pdf of the Tunisian constitution. We recommend reading the entire preamble. It is quite beautiful, and we wish we had space to include it.

This paragraph alone includes almost everything a high functioning constitutional democracy requires in order to accomplish egalitarian, pluralistic, self rule. Participation, unbloody alternation of power, free elections, separation of powers, pluralism, fair political competition, human rights, independent judiciary, and female suffrage and freedom enshrined in a political document: the bedrock of western democracy. Having a document that is worded in a manner that leaves little legal wiggle room, is a key ingredient for continued success after a revolution that overturned 60 years of presidential authoritarianism, but this does not guarantee perfect adherence to the norms established in the constitution nor does it mitigate the strong backlash Tunisia has seen from radical Islamists who have significant influence over large portions of the population.

Within this new constitution, Tunisia addresses several issues that have been a thorn in the side of the American democracy. The constitution establishes term limits for legislative representatives as well as for judges. It also imbues a dedicated constitutional court of 12 judges with the power to resolve budgetary and other constitutional problems that arise between the legislative and executive branches. Each government branch selects four constitutional court judges, ensuring the balance of powers over constitutional issues. Protected from corruption and elite capture, this democratic mechanism facilitates smooth government operation and resolves gridlock between the legislative and executive branches. Something that would be a much appreciated sight in the U.S., instead of watching legislators filibuster on the senate floor for days on CSPAN about their favorite ice cream, all because Republicans and Democrats are unwilling to cooperate. Tunisia does not know the joy of watching a filibuster on CSPAN.

Democratic Mechanisms

Of the Muslim countries that experienced rapid revolutionary change in the wake of the Arab Spring of 2010 and 2011, Tunisia was the only one to establish high functioning democratic mechanisms. Tunisia quickly did away with the autocratic power of the President and his unilateral control over security forces and the secret police. They managed to implement a new government without state collapse.

Tunisia has successfully passed Huntington’s two-turnover test with successful alternations of power between 2011 and 2018 from president Fouad Mebazaa of the Neo Destour party, to president Moncef Marzouki of the Congress for the Republic party, and finally with the incumbent president Beji Caid Essebsi of the Nidaa Tounes party. This is something easier said than done, especially in a country deeply divided between secular and Islamic traditionalist legacies. In the U.S., political participants understand that, through many iterations of power turnover, it is necessary that the output of the democratic process not be challenged. We saw how robust this is in the U.S. when the Supreme Court settled the crisis that arose over electoral recounts in Bush v. Gore (2000) as well as the brute fact of nearly 250 years of unbloody power transfers. In many parts of the world this sort of crisis results in the losing party not conceding. Then the tanks roll, and democracy dissipates. It is a highly illusive collective mobilization problem, but Tunisia transcended it.

For Tunisia this indicates widespread agreement and assent to the rules of democratic process, regardless of the outcome that the freedom machine spits out, and such agreement and trust is always fragile after revolutions. Security dilemmas often arise after a revolution because groups do not trust one another to not hijack elections and consolidate their own power over the ensuing government. For all groups to simultaneously relinquish the right to challenge results ex post facto posed incredible collective coordination and communication problems for the emerging Tunisian government between hardline secularist and hardline Islamist Salafist groups. This was achieved by the moderate Islamist party Nahdah successfully balancing the security concerns of Salafist Muslims and the secular Nida Tounes party before the 2014 elections. They maintained this role even after losing in the elections.

The judiciary seems to function independently of the executive and legislative branches and the constitutional court continues to perform its functions over disputes unharassed.

The U.S. State Department reports that Tunisia has also taken significant strides against government corruption.

Human Rights

As Tunisia consolidated and refined democratic processes, it incurred more resistance from the extreme religious right. Secularists continue to increase their seats in Tunisia’s unicameral legislative chamber. As this has occurred, government crackdowns on extremist activity have grown more and more willing to favor national security concerns at the cost of human rights and judicial process. Many perceive this as a liberal takeover intent on stamping out Tunisia’s cultural heritage and Islamic legacy.

Tunisia is currently one of 70 countries where homosexuality is illegal. Efforts from the Tunisian human rights commission are moving forward to revoke this and other Shariah based laws, such as female inheritance laws and the death penalty.

As these political shifts occur, they conversely produce an increase in Islamic radicalization. Thus, Tunisia, in its efforts to stomp out extremism and facilitate a pluralist society as stated in its constitution, has resorted to various methods of indiscriminate arrests, censorship, and unfair trials.

The U.S. State department reported that, “In May [2017] a court in Tozeur sentenced two journalists – a brother and sister – to six months in prison for “insulting a public servant” after they criticized security forces for regularly raiding their home, allegedly on suspicion their sibling was affiliated with extremist religious groups.” This is one amongst a number of indiscriminate, unilateral government action against suspected, but unproven, Islamist sympathisers. See the State Department report for more such instances.

“The government may initiate administrative and legal procedures to remove imams whom authorities determine to be preaching “divisive” theology.” and , “The penal code criminalizes speech likely “to cause harm to the public order or morality,” as well as acts undermining public morals in a way that “intentionally violates modesty.” These stipulations constitute a powerful scepter in the hand of the Tunisian government to dictate public discourse. It is difficult to say what the next administration might interpret as “divisive theology”.

There are numerous reports of religious profiling of Salafist Muslims on account of their traditional dress and beards and restriction of movement for Salafists within the country, “Since 2014 more than 500 individuals filed complaints with the Tunisian Observatory for Rights and Freedoms, saying the government prevented them from traveling due to suspicion of extremism, and in some cases apparently based on their religious attire. The media also reported police and security forces harassed some women who wore the niqab.

Tunisia’s Future

Currently, Tunisia is a liberal and democratic government that, out of fear of radicalization of its citizens and for its security, has marginalized and isolated a large portion of the religious right through extrajudicial means. Tunisia boasts of thwarting some 12,000 ISIS recruits from leaving the country since 2013. This is not reassuring.

It is not hard to understand why Tunisia’s rationale for these miscarriages of justice, considering that Tunisian born individuals are overwhelmingly represented in recent terrorist attacks, including the Charlie Hebdo and Nice France attacks, and among ISIS recruits. Radicalism is the greatest threat to an emerging democracy in an Islamic country aiming to prove to the West that Islam is compatible with western modes of governance. It is incumbent on the leadership of Nidaa Tounes and its current Tunisian President, Beji Caid Essebsi, to find a way to avoid using human rights violating and unconstitutional means in order to maintain national security. If the religious right is more isolated on the margins, it will undoubtedly be the unraveling of the democratic project in Tunisia.

As things stand at the time of this writing, the problem of resolving the dichotomy between liberal democracy and traditional Islam has not been so much resolved in Tunisia as it has been shunted aside, and therefore, thrives underground, providing an ever replenishing pool of candidates for radicalization.

Indonesia

Indonesia has a strong democratic constitutional platform but is deadlocked by corruption. The two political visions offers solutions to this “moral decay”: military-based nationalism and more explicit Islamic rules. Although Islamic political parties field candidates and do well electorally, Pancasila remains an important governing ideology for the archipelago, and no party can escape paying some lip-service to it.

History

Indonesian nationalism which began in the earliest years of the 20th century did not have a strong religious component. Christianity, Islam, and Hinduism had majorities in certain provinces of the archipelago, but Islam was the most dominant religion in terms of numbers. However, the Islam of Indonesia did not coalesce into a credible political force until recently. You will see why shortly.

Indonesian independence activists in the early 20th century had their sights set against the Dutch colonizers, who kept the Indonesian governments under their mercantile thumb, employing a race-based caste system. After 1900 early nationalists took up the term ‘Indonesia’, originally an ethnographic term coined by northern Europeans, and used it to raise awareness about the possibility of a unified nation. Through the 1920s groups formed using the name Indonesia and other groups incorporated ‘Indonesia’ into their title. Additionally, youth movements, socialist and communist parties, and Islamic financial solidarity groups formed to resist colonial exploitation. Into this caldron of budding nationalism, socialism, communism, Islamic consciousness, anti-colonialism, and national consciousness stepped the imperial Japanese occupying force.

The Japanese occupation did not maintain a light touch. The abuse of islanders in many different principalities impressed the need for a strong independent Indonesia upon the above groups; religious leaders, scholars, and activists mourned the occupation and abuse. During the end days of Japanese power, communist, Islamic, and nationalist resistance organized. Two days after Japan’s surrender to the United States on September 2, 1945, Indonesia declared independence.

The years following the declaration of Independence were fraught with guerilla warfare between the nationalist government, European colonizers, communist resistance groups, and (by the 1950s) Islamist resistance groups. The resulting political ideology of the state was called Pancasila.

Constitution

Pancasila (or “The Five Principles”) run as such:

- Belief in the One and Only God

- A just and civilized humanity

- A unified Indonesia

- Democracy, led by the wisdom of the representatives of the People

- Social justice for all Indonesians

What Pancasila means in practice for liberalism is that public atheism, agnosticism, and animism are illegal, and that outspoken criticism of the government can be considered and offense against the 3rd principle – a unified Indonesia. The leaders of Indonesia safeguard the country’s unity by force of arms and sometimes violent suppression. The central government goes to some lengths to maintain independence from “Great Powers,” so that their military forces can be concentrated on combating problems within the archipelago. Additionally, free market economics ought to be tempered by social welfare programs, and programs for mutual aid (these programs for mutual aid are very important in contemporary Indonesia, since in the present day explicitly Islamic institutions have created nearly all social safety nets).

The Indonesian constitution looks and reads like a liberal democratic constitution with some important idiosyncrasies. The strong centralized executive branch takes the lead over other branches and acts as balance against against the forces of decentralization and democratic impotency. We call this authoritarianism. While arguments about decentralization and federalism were at the heart of American politics in the early days of the U.S.A, for Indonesia the constitution provides the executive all the powers needed to ensure unity through force, which occurs regularly. Apparently archipelagos tend to resist centralization.

Articles 27 through 34 guarantee a cornucopia of human rights. The list is impressive and beautiful and a distant ideal. For our purposes I will draw your attention to Article 29:

Chapter XI Religion Article 29

(1) The State shall be based upon the belief in the One and Only God.

(2) The State guarantees all persons the freedom of worship, each according to his/her own religion or belief.

After the death of Suharto in 1998, a new debate emerged to define the role of Islam in the nonsectarian constitution. The options on the table for the revision of Article 29 of the constitution tell the story of the interests of political actors involved.

- The state is based on Belief in One Almighty God

- The state is based on Belief in One Almighty God with the obligation upon the followers of Islam to carry out Islamic law

- The state is based on Belief in One Almighty God with the obligation upon the followers of each religion to carry out its religious teachings

- The state is based on Belief in One Almighty God, Just and Civilised Humanitarianism, the Unity of Indonesia, Democracy Guided by the Wisdom of Representative Deliberation, and Social Justice for all Indonesians

The first option, original to the constitution, stuck.

The third option could lead to religious courts for all religious believers. In Indonesia there are only six officially recognized religions (Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism, and Confucianism); ID cards state religious identity on them. A system of personal status courts would require courts for each sect and would diminish the power of civil courts, leaving them to decide family cases outside the ken of the religion in question. Opening the door to a justice system with 6 different legal codes would not, we reckon, foster stability.

The fourth option reiterates the principles of Pancasila signaling recommitment to the Indonesia’s ideological roots.

The second option, of course, is the Islamic one which would enshrine in the constitution the role of Islam for believers and allow sharia law to be a basis for future lawmaking. The government in that case would obtain the potential to legislate away some of the autonomy and rights of non-Muslims and non-Muslim communities which are protected by Pancasila. Furthermore, the need for this law is suspect. In 1998 Law No. 7 gave Muslims the right to have personal status cases heard in Islamic courts if they wish. The push for the change to federal law revealed a possible future for Indonesia that would step decidedly away from the nonsectarian values of the state.

Although no textual change came of this constitutional debate, the lack of change affirmed the same non-secular, nonsectarian Indonesia which preceded the debate. This is good. Perhaps it even strengthened Indonesia’s political system. Nonetheless for us the disagreements illuminated schools of thought among the politically active in Indonesia.

Democratic Institutions

In the past 8 months over 300 elected officials have been implicated in corruption scandals. Corruption in the judiciary, civil service, and police force runs rampant. Efforts to crackdown on corruption are ongoing, as are counterterrorism efforts within the country. Between terrorism and corruption of elected officials, little faith remains in the power of democracy and liberalism to solve the problems of security and prosperity for Indonesia.

Businesses in Indonesia frequently have to grease the wheels of bureaucracy with bribery, and the cost of doing business is highly variable. During Suharto’s regime corruption was centralized and predictable. Decentralized corruption on the other hand makes transaction costs unpredictable, thus business has a more difficult time now than in authoritarian times. Additionally, corruption among the police and judiciary exacerbate costs, since the justice department can’t always be relied on to prosecute crimes efficiently or effectively.

Islam

Up to 2,000 Indonesian citizens have fought for ISIS. As these fighters return home, some seek rehabilitation, some carry out terrorist attacks, some promote Islamic State political visions. The government’s antiterrorism task force releases commercials trying to debunk the glorious Islamic State. Some returnees had to be threatened before they would swear allegiance to Pancasila; according to C-SAVE director Maria Kusumini, 90% of returnees want to live under an Islamic caliphate. While that is not an enormous percent for a country of 261 million, it’s still enough to cause problems for society.

Suharto brooked no opposition in his ~50 years of power. He restricted freedom of speech and reacted with military force against both Islamic and communist separatists. Debate about shari’ah in Indonesia was not permitted until 1998 with Suharto’s death. The many years that political Islamic expression sat impotent allowed the energies of Islamic organizations to flow into local communities of financial aid, health, and support. These organizations make Indonesia a strong country, but in the future their renewed political character might repeal and replace Indonesia’s founding principles.

Kazakhstan

The Republic of Kazakhstan is not an Arab country. Kazakhs are Turkic people, and their conversion to Islam did not come until well after the Mongol invasion (13th c.). Islam came late to Kazakhstan (15th c.) and conversion was a slow and inconsistent process for the traditionally nomadic people.

Eventually, Islam did spread to the itinerant people overtaking their traditional beliefs. The Hanafi school of jurisprudence remains the dominant school of Islam in Kazakhstan largely, some Kazakh scholars say, because it allows friendly relations with non-Muslims. Also note that Arabic Islamic traditions never became widespread among the tribes. The nomadism and lack of education ensured that the expression of Islam would be less tied to written interpretations, and more adapted for life on the road, while incorporating some syncretic elements from the traditional paganism of the region.

As happens on the steppe, slowly over the course of the 19th c. the great bear to the north, Russia, absorbed its unwilling southern neighbor, and thus Kazakhstan became part of the Russian Empire’s geopolitical strategy . Then came the Bolshevik revolution which first suppressed religion, then used some elements of the Islamic governance structure. The effect was a decimation of Islamic culture, traditional culture, and nomadism, balanced by Russification, secularization, and various other Moscow initiatives for economic modernisation. Results over the 20th c. were… mixed.

Independence came in 1990 and with it a resurgence of Kazakh population, decrease in Russian population and influence, return to various cultural expressions, namely Islam, and a new capital, Astana.

Post-Soviet Political Expression

Kazakhstan has many trappings of a Soviet state. The President holds power as an autocrat, not merely one actor among others in government. In fact, Kazakhstan has had the same president since 1990. The nation is officially secular, allows authentic freedoms, guarantees protection of citizen rights, but betrays such constitutional promises through corruption in law enforcement and the judiciary and suppression of political dissidents and “nontraditional” religious groups. The Constitutional Court has failed to rein in latitudinous interpretations of the constitution such as Article 5.3:

Formation and functioning of public associations pursuing the goals or actions directed toward a violent change of the constitutional system, violation of the integrity of the Republic, undermining the security of the state, inciting social, racial, national, religious, and tribal enmity, as well as formation of unauthorized paramilitary units shall be prohibited.

Or Article 20.3

Propaganda or agitation for the forcible change of the constitutional system, violation of the integrity of the Republic, undermining of state security, and advocating war, social, racial, national, religious, and clannish superiority as well as the cult of cruelty and violence, shall not be allowed.

The result of these statues is the heavy monitoring of all assemblies, especially religious assemblies. “Nontraditional religions” are censored. Missionaries and religious groups need state approval in order to operate. But the Jehovah’s Witnesses seem to always be finding themselves on the wrong side of the law, as do Baptists, and Muslims which do not subscribe to Hanafi Sunni Islam, or who read or are found in possession of “dissident” materials. At times Baptists have had difficulty operating in the country without being accused of unlicensed evangelism. Private religious reading is carefully watched by the state and is considered a national security issue overriding the “right to confidentiality.”

For political opposition, this spells doom. Opposition leaders, activists, and journalists find themselves fined, imprisoned, and exiled. Even academics, according to the U.S. State Department (see link above), self-censor for fear of “infringing on the dignity and honor of the president and his family.”

There are few prospects for Kazakhstan to become a more liberal and democratic society any time soon. Instead, by the example and logic of its neighbors (the other four -Stans, China, and Russia), authoritarian power and pervasive opportunism preserve the government of Kazakhstan.

Islam in Modern Kazakhstan

The suppression and control of Islam during Soviet rule further isolated the country’s culture and reduced the transfer of Islam to the next generation. As glasnost gave some wiggle room for religion in Kazakhstan, Islam and Russian Orthodoxy reestablished themselves. The Christian population (mostly Russian Orthodox) declined from 46% in 1994 to 26% in 2018 due mostly to Russian and other Slavic emigration. Islam gained momentum in the 90s going from 44% of the population in 1994 to 70.2% in 2018. Only around 5% percent of this change is from Islamic population growth.

As Islam has grown, government initiatives to control Islamic expression have grown too. One of the reasons for this is education. Better educated Muslims are more informed about the rest of the Islamic world and thus more uncomfortable with Kazakh Islamic idiosyncrasies and syncretisms. Social movements inspired by the more politically charged Islam of Afghanistan, Iran, and Indonesia has led to government crackdown. Islamic cultural symbols such as the hijab are banned in schools, dressing in an Arabic Islamic way can be punished, and many Islamic organizations are banned, especially Salafist adjacent movements. Meanwhile the government is also taking positive steps to use the muftiate of Kazakhstan to define a specifically Kazakh Islam. Whether Kazakhstan can create an effective state-sponsored Islam, the way a country like China has created a state-sponsored Catholicism, remains to be seen.

Sadly, human rights seem to be an afterthought in Nazabayev’s government, as political dissidents are shut-down, both in the streets and online, thanks to China-esque internet surveillance. While Islam is treated as part of the national heritage, any expression, or suspected expression of Islam deemed too extreme gets the accused convicted of political dissidence. And similarly, political dissidents can be labelled extremist Muslims and thus convicted. While some see in this repression a potential for backfire against the government, more likely, the coercive binding of the Overton Window will serve its purpose and reduce dissent and the public sphere, so long as Kazakhstan’s government can merely cite national security concerns to work its will.

Islam is not a political force in the country. You would think that a Muslim majority country would have a more “Islamic character,” but Kazakhstan’s political history puts religious expression in a context of post-Soviet authoritarian secularism. The Islam of Kazakhstan is young and develops along government initiative; public political religion is just not possible. Kazakhstan is secular, just not in a way that a human rights activist would celebrate.

Iran

History

Iran experienced a number of conquests and periods of cultural enrichment and decline between the conquest of Alexander the Great (330 B.C.) and the Safavid Empire (1501-1732), which ruled roughly the same geographical parameters as modern day Iran.

The 7th century Islamic conquests altered Persian society dramatically, and permeated Persian culture deeply, competing with longstanding Zoroastrian and Byzantine Christian cultures. Not long after Islam established itself in Iran, the Shiite and Sunni schism occurred over the prophet Mohammed’s heirs. This would prove to be the proverbial line in the sand, setting the stage for a millenia long regional split between the two Islamic schools. This dynamic fundamentally informs many of today’s conflicts in the Middle East. See the conflict in Yemen and the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988).

We saw in Tunisia that postcolonial, secular authoritarian leaders were able to successfully implement industrial and political modernization over the latter half of the 20th century without inciting backlash from Islamist traditionals. A similar effort began in Iran in the early 20th century with the Constitutional Revolution of 1905-1907, Iran’s first efforts with democratic norms of popularly derived rule and self identification as a sovereign nation state, something ever illusive in Iranian history. It collapsed quickly into chaos. After Russian intervention in Northern Iran threatened the stability of the country, Britain switched support from the Constitutionalists to the Shahs, who were the ruling monarchy before the revolution. Reza Shah seized power in 1921, reestablishing monarchical rule with significant control over parliamentary systems.

Reza Shah embarked on a modernization campaign with ambitions to make Iran a regional power and globally competitive economic entity, free from foreign interference by Russia and Britain. Reza Shah also dramatically increased the centralization of the state and strengthened the military.

This process came to a head with the 1951-1953 oil crisis, known as the Abadan crisis, when Iran nationalized the Anglo-Iranian-Oil Company (AIOC) assets. While this did prompt a British and U.S. supported coup d’etat which ousted democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in favor of consolidating the monarchical rule of Mohammad Shah, Iran had vast undercurrents of political disaffection as economic modernization efforts dating back to 1925 continued to leave behind rural Islamic communities. Known as Operation Ajax, the CIA fomented support for Mohammad Shah and organized guerilla forces to discredit Mosaddegh’s government. Iran was primed for this operation to work, as Mossaddegh’s socialist rhetoric alienated Iran’s conservative Islamic population.

In 1979, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini executed a successful Islamic revolution that ousted the American backed government in favor of a new theocratic government which is still in power today and is of rising importance in Middle Eastern affairs.

Radical Islamic Ideology

Ernest Gellner’s theory of Folk-Islam and High culture-Islam provide a compelling explanation for the causal sources of the Iranian Revolution of 1979 in addition to the coercive effects of interventionist U.S. foreign policy.

Gellner distinguishes between High-Islam and Folk-Islam. High Islam is deeply austere, literate, and connected to a fundamentalist reading of sacred texts. It is often associated with more elite society in urban areas. Folk-Islam on the other hand, is grounded more in community and local tradition within the illiterate rural population. Folk-Islam is analogous to the nomadic and moderate Islam that we discussed as the prevailing style of Islam in Kazakhstan. In Iran, Gellner asserts, the influx of Folk-Islamic peoples into urban areas as a result of rapid industrialization in the mid-20th century, where High-Islam predominated, in conjunction with aggressive interventionist foreign policy of the U.S. and Britain in the 1950s, produced perfect storm conditions in 1979 for Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and a coalition of conservative clerics to incite a popular uprising and seize control of an unstable country that had been abused by foreign powers and had a deeply dissatisfied lower class.

The ensuing Islamic Republic of Iran identifies less as a sovereign nation state, and more as an ideological cause whose purpose is to expand the umma (the community of all Muslim believers), to all corners of the world, eventually absorbing all the lands of the infidels. This obviously has posed serious problems to the international order. Iran does not play by Westphalian rules of statehood and self determination. It sees itself as the vanguard of the divinely ordained mission to establish the reign of God on earth.

Hassan Abbasi, head of the Iranian think tank, associated with the Revolutionary Guard (which is under the personal command of the current leading Ayatollah), Center For Borderless Doctrinal Analysis, argued that the Islamic Republic could not be safe unless it persuaded other Muslim nations to take the same path. “If we remain alone, we will always be in danger,” he said. “Our system will also be in danger if most Muslim nations take the path of Western-style democracy.” Abbasi also asserted that Iran’s mission overrides borders and state sovereignty which are, in his estimation, “colonial inventions”. Khomeini spoke often of the need to export the revolution to other Muslim countries and to liberate Palestine and Jerusalem. These notions are fundamental in Iranian foreign policy today.

Constitution

The introduction and preamble to Iran’s constitution reads more like propaganda than a legally binding document. There is much talk of saints and martyrs’ blood, as well as the imposition of deity-like characteristics to the Ayatolla,

The honorable source of emulation, the great leader of the global Islamic Revolution, and the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the venerated Grand Ayatollah, Imam Khomaini, may his noble character be sanctified, who was acknowledged and accepted by the undisputed majority of the people as the marja’and the leader. Iranian Constitution Article 107

The Ayatollah holds the final decision over all jurisprudential matters, is commander of the military and security forces, as well as the Islamic Pasdaran Revolutionary Corps. He is the only individual who may amend the constitution with a two thirds confirmation from the Islamic Consultative Assembly. The assembly does wield limited legislative powers, but not on anything that, “Contradict[s] the canons and principles of the official religion of the country or the constitution. The Guardian Council is responsible for the evaluation of this matter.” Article 72. The Ayatollah heads the Guardian Council. Thus, the delegating of any executive, legislative, or judicial power to anyone but the Ayatollah is always qualified in a manner that allows the Ayatolla to frame any issue as, “Contradicting the canons and principles of the official religion” in fact, give him unassailable and arbitrary control over government.

Some democratic principles are enshrined in the constitution, such as popular secret elections of legislatures and of the president. Political parties are allowed to exist on the same basis as legislation, so long as it does not contradict the religious canon. Again, they are flimsy.

The constitution also benevolently condescends to return women to their true dignity in replacing them upon the resplendent and exalted pedestal of true womanhood, in their calling to motherhood.

Women are emancipated from the state of being an “object” or a “tool” in the service of disseminating consumerism and exploitation, while reclaiming the crucial and revered responsibility of motherhood and raising ideological vanguards. Women shall walk alongside men in the active arenas of existence. As a result, women will be the recipients of a more critical responsibility and enjoy a more exalted and prized estimation in view of Islam.

Iran Constitution, page 6.

Why is it acceptable for men to be “tools” and “objects” of exploitation and consumerism, but not women? The consequence of this is that women are relegated to child bearing and home-managing responsibilities only.

These points indicate a constitution that is neither democratic nor liberal.

Democratic Mechanisms

Political parties are allowed to exist so long as they do not challenge religio-political dogma. Roughly 11 parties exist that command any significant following including a reformist party, but this does not mean that a wide window of public discourse exists. The spectrum of political opinion is severely limited by the broad terminology in the constitution as to what is acceptable in public debate, and the Ayatollah’s power is arbitrary as to determining what is religiously or politically admissible. Thus, the democratic nature of party politics and free elections is misleading at first take. In reality, political opinion is dictated almost entirely by the Ayatolla and the clerics.

Reformists?

Iran’s best hope for change, since we are assuming it would be a toss up over which would be worse between maintaining the status quo and a regime change operation carried out via a U.S. led coalition, is The Council For Coordinating the Reforms Front organization. Led by former president Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005), who instigated intense internal debate during his presidency between his administration, and the conservative clerical elites and the Ayatolla. Khatami led reform efforts during his presidency with two government reform bills intended to limit the power of the Guardian Council to select candidates for political office as well as limit other constitutional powers of the judiciary. The Guardian Council is selected by the Ayatolla and is responsible for investigating infractions against religious and political doctrine. Every time a reformist minded candidate arises, the Guardian Council hammers them with claims of kafir and they are banned from running. Khatami’s two bills would retract the power of the Guardians to ban candidates as well as allow the executive to reprimand constitutional bodies like the Guardian Council and the Experts (a judicial body body charged with selecting the Ayatolla) for arbitrary decisions. Both bills failed under the pretext that this was a power grab by the executive, instead of an intended balancing of power between government branches. They were also deemed unconstitutional by the Guardian Council. After 2005, the Reform effort was deemed dead by reform theorists like Saeed Hajjarian.

Clerics have continued to win most political battles since the early 2000s as they have a firm grip on the lower class poor, but with a rising middle class, some reformists maintain optimism of pushing reforms through in the near future. In 2017, 28% of Iranians identified as leaning Reformist. In comparison, 15% identified as leaning Principlist. Despite this, a large number of reform activists wrote an open letter to Khatami demanding a “Reform of the reform”. After the demonstrations earlier this year yielded no apparent results, younger Iranians are beginning to see the reformists as merely a political party that has been assimilated into the Iranian clerical authoritarian structure.

Conclusion/Future Considerations

The only possible imminent change to the government in Iran would be via external imposed regime change. Reform efforts are easily suppressed through the legitimate mechanisms instantiated in the constitution. The Ayatolla is unlikely to be pushed to a point that might force him to do something unconstitutional, because he has all of the tools he needs in the constitution already. He is able to maintain this control while still allowing for regular assembly elections. It’s the holy grail of authoritarian control. The constitution allows the unitary leader various avenues of venting and mitigating efforts for change, while still refreshing the active participation of civil society in government decisions and keeping them engaged in the revolutionary cause.

Lots of think tanks like the Atlantic Council and other western publications love to talk about how much simmering discontent there is lying beneath the surface in Iran, but I do not buy this. This form of radical Islam has co-opted democratic mechanisms in such a manner that a less than pareto-optimal equilibrium has formed such that the democrat instruments themselves are used to prevent improvement in democratic norms and human rights.

Lebanon

The big story in Lebanese political society is the multiconfessional state. By law the President is always a Maronite Catholic, the Prime Minister a Sunni Muslim, the Speaker of Parliament a Shiite Muslim, the Deputy Speaker and Deputy Prime Minister are Greek Orthodox. The ratio of Christians to Muslims in Parliament until this past election was – by law – 1:1.

This internal sectarian balance of power system is described everywhere as ‘fragile.’ The evidence for this fragility is the protracted 15 year civil war which tore Lebanon apart until 1990 and sears into Lebanese political consciousness today, and the brute fact that a proper census has not been conducted since 1932. The prospect of a census sends horror down the spines of every religious and political leader, for whatever the outcome of such a census, it could throw open the floodgates of renewed sectarian demands followed by violence.

The Sectarian System

Although this does not sound like a promising start for a democracy, the state certainly functions within the basic scope of a democracy: elite capture and tyranny are not a concern. In fact, the sectarian balance-of-powers structure maintains basic democracy through its quotas and coalitions. Government power comes from the consent of the sectarian leaders who can work to come together, address the latest crisis, and ultimately, play fast and loose with the constitution to solve the needs of the moment.

France created Lebanon out of Greater Syria in 1926; from this original constitution the confessional balance-of-power system was born. However, the French ensured that western leaning Christian groups had more power in the government, since they would be more likely to favor French interests. The civil courts were based on a Napoleonic variant, and the government included a French high-commissioner who could suspend the constitution and establish direct rule.

When the Lebanese declared independence in 1943, norms needed to be established for the balance of power. These new norms were called The National Pact. The National Pact reaffirmed the sectarian status of offices: President (Maronite), Prime Minister (Sunni), Speaker of the Parliament (Shia), Deputies (Greek Orthodox), Commander of the Armed Forces (Maronite), Army Chief of Staff (Druze). It also reaffirmed the 6:5 representation of Christians to Muslims in Parliament based on the possibly manipulated, already out-of-date 1932 census. What’s important to add here, though, is that National Pact required Maronites to express their identity as non-Western Arabic, and that Muslims not seek incorporation into Syria. This Christian promise of an Arab identity for the country is crucially important for its international relations to this day, while the Muslim promise helps guarantee the spirit of Lebanese independence in the region.

The Civil War 1975 – 1990 was long and we will not get into the weeds of it. However there are some important lessons about Lebanon from the civil war. The coalitions of the civil war shifted around fast, and the political situation deteriorated from political ideology to confessional lines. The “leftist” opposition was made up of a coalition of pan-Arabs, Greater Syrians, socialists, and Islamists, while the ruling right was made of nationalists, fascists, and hard-line Christians. These coalitions broke apart fairly quickly and soon all that mattered was regional control and serving the needs/prejudices of those constituents. Since regions were fairly homogenous in their religious make-up, these regions assumed sectarian agendas and biases. This led to provocations everywhere followed by Israeli invasion, Syrian invasion, and UN Military Action, Iranian supplies to Shia militias, and ubiquitous atrocities. Although commanders of the varying forces were often of the same religion, the soldiers hailed from any sect. For example, the Shiite leadership of the Amal and Hezbollah militias were often fighting their coreligionists who were under Maronite leadership.

To bring the Lebanese Civil War to a close Saudi Arabia hosted the 1989 Taif Agreement. The agreement was brokered behind the scenes by the survivors of the 1972 parliament and its Speaker Hussein El-Husseini. The purpose of the agreement was to end the civil war, bring back rule of law, and reestablish an independent Lebanon. Additionally, the agreement changed some legacy problems from the French days. Once the French high-commissioner became a non-existent position, his powers were rolled up into the presidency. This gave the Maronite president a lot of power. He could, for example, dismiss the Prime Minister if he did not get along with him, giving the Christians a lot of power. This power was revoked in the agreement and the Christian – Muslim representation in Parliament was changed to 1:1.

Over the next years, Hezbollah, with the tacit consent of the central government, tried to reclaim the south from Israeli occupation. Since Taif (up to the present) the government has tried to diminish Hezbollah’s extra-governmental military operations, and lastly the country began extracting itself from rule/occupation/influence of Syria. However, since Palestinian-aligned militias controlled south Lebanon, and Syria controlled the north and east, the central government was still fairly weak and peace was uncertain. The Cedar Revolution (2005) pushed the Syrians out, and in 2018 Lebanon made credible strides into an independent future by means of its first parliamentary election since 2009.

The June 2017 electoral reforms divided Lebanon into 15 districts, lowered the voting age to 18, and allowed oversees Lebanese to vote. Here’s how it worked, and by the way, this is the most complicated voting system I have ever seen:

- Each district had a set number of seats per sectarian group.

- Political parties field a candidate for each of those seats in a registered candidate list.

- Citizens of the district get one vote per seat.

- Then the candidate with the most votes fills the respective seat.

Let us give an example. In the region “Beirut II” there were 6 Sunni seats, 2 Shia seats, 1 Druze seat, 1 Greek Orthodox seat, and 1 Evangelical seat, 11 seats total.

9 political parties formed to create a list of candidates for each seat. Citizens then cast 11 votes divided by sectarian confession. In theory there could have been 99 candidates up for election in Beirut II; however dropouts reduced the number of candidates to a still staggering (by U.S. standards) 82. While Beirut II is an outlier with its glut of nine political coalitions, the national average was still 5 – 6 lists per district.

The new system requires political parties to become interreligious coalitions which support a political platform, and since it relies on citizens casting votes for people outside their sect, the principle of consensus governance is preserved while decreasing sectarian tensions. Additionally, political interest groups are incentivized to work together to create consolidated candidate lists to reduce unwanted competition.

The big news item in the 2018 election was that the majority Future Movement party got smashed and Amal-Hezbollah won big. (Amal-Hezbollah is so named because the parent group, Amal, reunited with the splinter group Hezbollah.) Looking deeper Amal-Hezbollah made coalition lists with Free Patriotic Movement (mainly Christian center-right), Al-Ahbash (Sufi activists, because you can never have enough Rubaiyat), and Syrian Socialist Nationalists (yes, founded in 1932…). The triple decimation of the Future Movement and double rise of Free Patriotic Movement along with Amal-Hezbollah is a big move towards friendliness with Syria. At first blush this makes no sense. Isn’t Syria in shambles? Why be their ally? It is important to note though that these groups which won big in the most recent election were not part of the Cedar Revolution which pushed Syria out of Lebanon. Allowing Hezbollah militias freedom to actively support Assad may be the quickest path to relieving the pressures of 1.4+ million Syrian refugees in terrible camp conditions. (Furthermore, the Greater Syria ideology or a new Nasserism might find itself back on the table.)

In the Syrian Civil, Iran supports Assad’s government. They have set up forward military bases in Syria. We should not expect those to go anywhere anytime soon. While Iranian forces shuffle through Iraq to get to Syria, Lebanese Hezbollah fighters aid Assad from the east. Hezbollah’s military arm is funded in part by Iran, and the Iranian interest is to create an effective anti-Israel alliance. The Israeli response to Iranian troop in Syria has been frequent rocket strikes.

The political leaders see the 2017 reforms as the first step in a series to fix the sectarian system to create a more unified country. More reforms will be on their way. The next parliamentary election should occur in 2022. If it is a success, Lebanon may take one more step into security, prosperity, and, we hope, a nonsectarian future. As it is, Lebanon has to try to preserve its internal peace in a dangerous and high variance political environment.

Rights: The Cedar Package

“Lebanon has an Arab identity and belonging. It is a founding active member of the Arab League, committed to its Charter; as it is a founding active member of the United Nations Organization, committed to its Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The State embodies these principles in all sectors and scopes without exception.

Lebanon is a democratic parliamentary republic based upon the respect of public freedoms, freedom of opinion and freedom of belief; and of social justice and equality in rights and duties among all citizens, without distinction or preference.”

- Preamble to the Constitution B – C

Lebanon has not lived up to these UN notions of Human Rights. As often happens in the Lebanese constitution what is said in one part is qualified or contradicted in another. Articles 9 and 12 add important qualifiers to freedom of speech:

Article 9 “Freedom of conscience is absolute. In assuming the obligations of glorifying God, the Most High, the State respects all religions and creeds and safeguards the freedom of exercising the religious rites under its protection, without disturbing the public order. It also guarantees the respect of the system of personal status and religious interests of the people, regardless of their different creeds.”

Article 12 “The freedom of opinion, expression through speech and writing, the freedom of the press, the freedom of assembly, and the freedom of association, are all guaranteed within the scope of the law.”

“Without disturbing the public order”, “guarantees the respect of the system”, and “within the scope of the law” provide the judicial framework for blasphemy laws and prosecution for opinions outside the Overton Window. But the Overton Window of Lebanon is extremely wide, from Communists to National Socialists, from conservative Shiites to Gay Pride promoting Sunnis.

While freedom of worship is guaranteed, freedom from religious institutions is not. Lebanon has a civil judiciary for general property rights, prosecution, and so on, but what we call family law is the province of religious courts. Marriage, inheritance, child custody, annulment, divorce are all controlled by 15 or so religious courts. Most everyone is labelled a member of a sect, even if not practicing, for the purposes of family law. These laws are the strongest legal force entrenching sectarianism in Lebanon. And, unfortunately, they often relegate women to second class status.

The Right to Rock and Roll

The current picture of Lebanon would not be complete without a few words about Lebanese culture. Lebanon is one of the most culturally productive and free Arab countries. It maintains itself as a regional media capital. Rock music, cinema, and books are produced in Lebanon and exported all over the Arab world.

Seriously, the music is great!

More about Islam

Recently, interfaith marriage has become possible, and from that marriage has issued a sectless baby. The marriage required the signature of the Minister of the Interior. Small demonstrations have called for civil marriage as a civil right. Despite these developments, Lebanon is not necessarily on the way to becoming a country which accepts secularism into its internal balance.

Sunnis and Shiites are equal in number – both being about 27% of the total citizen population. Druze make up 5%, and they are grouped as Muslim for political purposes. We don’t know that they would call themselves Muslim, since they consider the Dialogues of Plato an inspired text, and look to their own sacred texts and precepts. Political battle lines in Lebanon concern Palestine and the Palestinians in Lebanon, Israel, the role of Hezbollah in society, the role of Syria in Lebanon, preservation of identity, and some type of identity politics based on the struggles of the last 30 years. The major political parties have a narrative and some vision for Lebanon, but at the same time contain members from many religious confessions.

Problems, Predictions, and Possibilities

So given all the instability in Lebanon’s history, why include it in the study? It does seem to break our rule of inclusion since its Muslim citizen population is only ~60%. However, it is an example of diversity, dynamism, political balancing, and cultural production in the midst of a weak state apparatus.

Currently, Lebanon has a citizen population of ~5 million. An additional 400,000 Palestinians and 1.5 million Syrian refugees are also within the borders with little prospects for the future. Most of these people are Muslim, and so will probably not become naturalized citizens any time soon. Currently Lebanon’s government sees hope for the return of Syrians to their home country, even as the Palestinians hang in a hopeless limbo.

For Lebanon to extend its civil rights, greater control of the border must be secured. The first requirement is the cessation of the civil war in Syria. The second requirement is a second parliamentary election which further diffuses sectarianism and entrenches democratic norms. At the local level, interfaith marriage and conversions would assist the project of desectarianism by creating more demand for civil courts to handle some family law.

Conclusions

The intersection of Islam and liberal democracy is a recent phenomenon that began with decolonization in the early 20th century. These countries ratified their constitutions between 4 and 75 years ago; thus we should expect generalizations to be error prone. This data set, while chosen with the goal of being as representative a sample of the population as possible, is still small and requires further investigation. Our study and synthesis, we believe, provides a good starting point for subsequent work in an area that we found to be thin on academic literature.

We also saw that this method, to our knowledge, has not been implemented before. Most of the work we found on Islam and liberal democracy, expressed itself primarily in the realms of abstract political theory, philosophy, and theology. By examining a diverse segment of the Islamic world’s history, constitutions, and political institutions, we hope to make more confident claims about its relationship with liberal democracy than other methods have been able to as of yet.