Introduction

ADHD is typically considered a disorder of attention and focus. There are various other traits everyone knows are linked – officially, hyperactivity and “behavior problems”; unofficially, anger and thrill-seeking – but most people consider these to be some sort of effect of the general attention deficit.

Dr. William Dodson pushes a different conception, where one of the key features of ADHD is “rejection-sensitive dysphoria”, ie people with the condition are much less able to tolerate social rejection, and more likely to find it unbearable and organize their lives around avoiding it. He doesn’t deny the attention and focus symptoms; he just thinks that rejection sensitivity needs to be considered a key part of the disorder.

I say “Dr. William Dodson pushes”, but this requires a little research before it becomes apparent. What a Google search shows is just a bunch of articles saying that rejection sensitivity is a key part of ADHD that gets ignored by non-expert psychiatrists and that it’s important to educate patients about it and include it in any treatment plan. My conclusion is that all of these articles can be traced back to Dr. Dodson or people inspired by Dr. Dodson, of which there are many. The ADHD patient community has gotten really into this and pushed it in a lot of support groups and patient communities and so on, where it is repeated uncritically as “an important ADHD feature psychiatrists often forget about”. But the genesis is just Dr. Dodson saying so, with limited formal evidence.

See for example ADDitude Magazine, which says that:

Rejection sensitivity is part of ADHD. It’s neurologic and genetic. Early childhood trauma makes anything worse, but it does not cause RSD. Often, patients are comforted just to know there is a name for this feeling. It makes a difference knowing what it is, that they are not alone, and that almost 100% of people with ADHD experience rejection sensitivity. After hearing this diagnosis, they know it’s not their fault, that they are not damaged.

…and suggests very high doses of alpha-agonists or MAOIs (!) as a treatment. Or WebMD, which says:

Up to 99% of teens and adults with ADHD are more sensitive than usual to rejection. And nearly 1 in 3 say it’s the hardest part of living with ADHD.

Neither article cites any sources.

I am skeptical of the rejection-sensitive dysphoria concept. Part of it is the lack of evidence beyond Dr. Dodson’s personal experience, which my own personal experience contradicts. But part of it is that it seems suspicious for the Forer Effect, the tendency for everyone to believe a generic statement describes them especially. This effect is beloved of psychics – tell a client a few Forer statements and they’ll walk out convinced you can read minds – but it causes problems in the more reputable sciences as well. Here is Forer’s original list of statements that produce the effect:

1. You have a great need for other people to like and admire you.

2. You have a tendency to be critical of yourself.

3. You have a great deal of unused capacity which you have not turned to your advantage.

4. While you have some personality weaknesses, you are generally able to compensate for them.

5. Disciplined and self-controlled outside, you tend to be worrisome and insecure inside.

6. At times you have serious doubts as to whether you have made the right decision or done the right thing.

7. You prefer a certain amount of change and variety and become dissatisfied when hemmed in by restrictions and limitations.

8. You pride yourself as an independent thinker and do not accept others’ statements without satisfactory proof.

9. You have found it unwise to be too frank in revealing yourself to others.

10. At times you are extroverted, affable, sociable, while at other times you are introverted, wary, reserved.

11.Some of your aspirations tend to be pretty unrealistic.

12. Security is one of your major goals in life.

The first statement sounds a lot like rejection sensitivity. I will admit that one of the strongest pieces of evidence in favor of rejection-sensitivity dysphoria is all the ADHD patients who comment on any article about it with “Wow, this perfectly describes my experience! This is amazing!” – but if it were a Forer Effect, this would be less surprising.

There have been two studies attempting to investigate the ADHD-rejection link. The first, Canu & Carlson, failed to find it. The second, Bondu and Esser, did find it. This may be because the second had a larger sample size. But the second also correlated rejection-sensitive dysphoria with ADHD symptoms, rather than relying on an ADHD diagnosis. It also failed to screen out other psychiatric disorders, many of which are comorbid with ADHD and look a lot like rejection sensitivity (eg anxiety, depression). Overall this does provide some support for the hypothesis, but so far it looks like the only attempt to formally test it.

Methods

I investigated the idea of rejection-sensitive dysphoria through the Slate Star Codex survey, an online survey of readers of this blog. It received 8,077 responses, including 717 people with professionally-diagnosed ADHD, 860 more people with self-diagnosed ADHD, and several thousand with other psychiatric conditions.

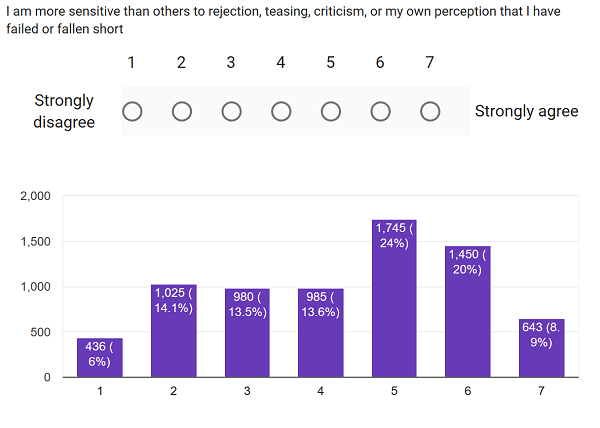

The survey contained the following question:

I am more sensitive than others to rejection, teasing, criticism, or my own perception that I have failed or fallen short

This is a standard screen for rejection-sensitive dysphoria quoted as Dr. Dodson’s proposed addition to the DSM diagnostic criteria for ADHD (though I cannot find confirmation of this from Dr. Dodson himself). Most of the citations frame it more strongly, eg “For your entire life have you always been much more sensitive than other people you know to rejection, teasing, criticism, or your own perception that you have failed or fallen short?”. I cannot remember why I made the survey version weaker and this is a weakness of this study. Respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement with this statement on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

The following analysis strategy was devised before looking at any data: to compare people with ADHD only to people with no psychiatric condition, to people with only one other psychiatric condition, and to people with multiple psychiatric conditions. The three other conditions with a large enough sample size to use were autism, anxiety, and depression. Analyses were done both among self-diagnosed patients and professionally diagnosed patients. I committed to publishing this post regardless of what the analysis said.

All other analyses were done after seeing the data, and should be considered exploratory only.

Results

7,264 people answered the question about rejection-sensitive dysphoria:

There was a slight bias towards affirmative answers, consistent with a small (but not large) Forer effect.

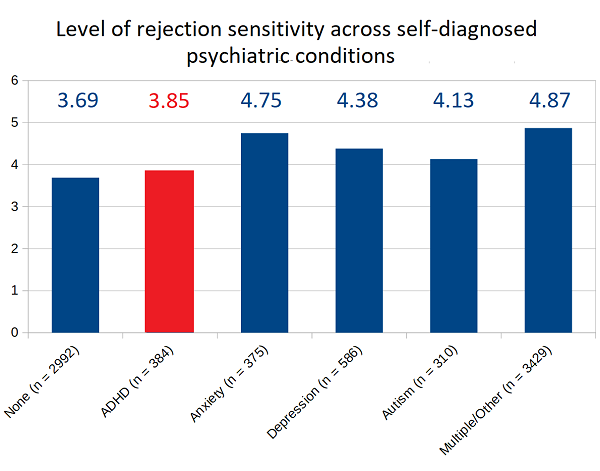

Among people with self-diagnosed psychiatric conditions, answers varied as follows:

ADHD had the lowest rate of rejection sensitivity among the four psychiatric conditions studied, although it was still higher than people with no condition.

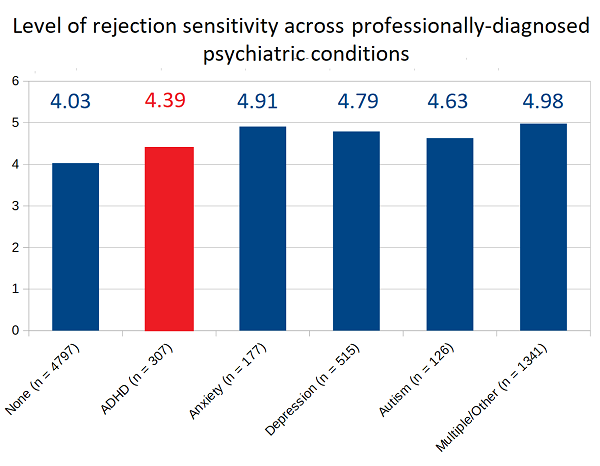

Among people with professionally-diagnosed psychiatric conditions, the picture was much the same:

Once again, ADHD had the lowest rate of rejection sensitivity among the four psychiatric conditions studied, but was higher than people with no condition.

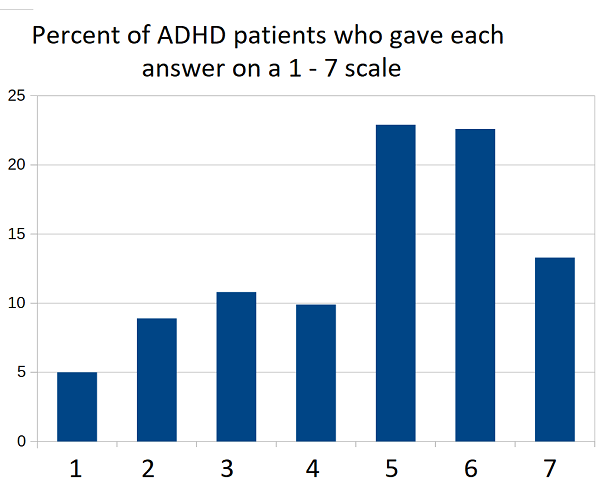

Articles alternately claim that “99%” “99.9%” or “almost 100%” of people with ADHD endorse rejection sensitive dysphoria. My survey found less dramatic results:

58.5% of ADHD patients gave answers of 5, 6, or 7 on a one-to-seven scale of rejection sensitivity. This was statistically significantly different from the 46.2% of the general population who did the same, but not in nearly as impressive a way as suggested by the 99.9% numbers that some people quote.

Discussion

My survey found that there was a weak but statistically significant tendency for people with ADHD to have higher rejection sensitivity than people without psychiatric conditions. However, this was a general tendency for any psychiatric disorder, and ADHD had the lowest rates of rejection sensitivity among the four disorders studied. This suggests the conception of rejection sensitivity as fundamental to ADHD is inaccurate and should not be included in discussions of the condition.

Flaws in this study include the survey methodology, which relied on self-report to get each respondent’s diagnosis or lack thereof. On a deeper level, if the current conception of ADHD is fundamentally flawed because of ignoring rejection-related symptoms, then no diagnosis using the current method can be trusted. But to call something ADHD at all, rather than a completely new illness, requires that it have some correlation with ADHD features as classically understood. Given that there is no generally-accepted objective measure of ADHD, these diagnoses are the best measurement we have at this time.

Other flaws included the admittedly weak single-question test for rejection sensitivity, the inexplicable softening of the single question from its classic version, the lack of adjustment for any confounders, and the heavily selected sample of SSC readers.

However, it is still difficult to argue with the magnitude of the result in a large sample size such as this one. ADHD has the least rejection sensitivity of any of the disorders studied. None of the flaws in this study seem to be of the type or the magnitude that could incorrectly produce this result.

I conclude that it is important to beware of Forer effects in ideas about psychiatric symptomatology, especially ideas that spread among patient groups without formal study or buy-in from researchers. Forer statements are often vague, slightly self-flattering, or suggest that the person involved needs special care or respect from others. Since most people feel this way, it may be easy to convince people with a condition that the condition implies a Forer statement. My informal survey does not support this connection at this time. Other teams should follow up with more formal experiments to try to confirm.

It’s always felt to me like a combination of forer statements (I’ve always known them as Barnum statements, ie ‘there’s something for everyone’) and the sorta natural personality consequences of growing up with ADHD, particularly inattentive type, particularly undiagnosed. So in as much as it’s a thing, it feels to me like a consequence of some people’s life history with the condition, rather than an integral part of it.

Idk where the origin of this idea is but I’ve heard of it as specifically more a ‘women with ADHD’ thing- which would make sense as being female correlates with being Inattentive type and late diagnosis.

“a small (but not large) Forer effect”

If it’s small, how can it also be large. Isn’t the parenthesis redundant.

Your first approach is fundamentally flawed because it puts ‘multiple/other’ in its own separate category, thus excluding comorbid conditions. This then tautologically leads to your hypothesized outcome, because rejection sensitivity is a key hallmark of anxiety disorders and would thereby result in ‘multiple/other’ and be excluded from the ‘ADHD’ category.

Only your second approach genuinely addresses the issue at hand, by including all individuals with ADHD. It finds that rejection sensitivity is correlated with ADHD. It does not matter whether you call it a separate disorder or not; the condition is indeed correlated.

As a comment to the various people talking about rejection dysphoria as a rational response to people’s mental health conditions: the point is that it ISN’T. It’s not rational.

I recall once reading someone’s blog where he talked about an unpleasant person he’d met at an event. This event took place in a country I had never been to. It still felt like he must be talking about me. He has never met me, I have never been to that event, and the thing the person at that event did is not a thing I would ever conceive of doing. Yet I was still, on some gut level, sure he was talking about me.

It’s not just that you think everyone will reject you. It’s that everything everyone does is proof of rejection. EVERYTHING.

This may or may not be an integral part of ADD (or other disorders), but I strongly doubt it is a learned response to the experience of having a mental illness. It may simply be its own thing that should be parsed out into its own disorder, but it’s not rational and certainly does exist.

EDIT:

Also, it absolutely would make sense as part of any executive processing disorder – you put too much importance on the wrong stuff. The path by which that would lead to rejection dysphoria seems fairly evident.

I’d bet you’d find higher levels of rejection sensitivity among the chronically ill in general — and particularly among those with “invisible” diseases.

From Virginia Woolf to Susan Sontag to Porochista Khakpour, women mostly have pointed out that culture — even literature — has typically had very little tolerance of, or interest in, sick people. Woolf believed that to be sick, or even to be a dedicated ally of the sick, is to be subversive; that is, you have landed outside the game, and all your interactions with gamers have become one-sided: your perspectives and narratives are afforded no validity or agency. You, being unwell, are expected to defer to (the well) outsiders’ declarations about your condition. You’d have to be an exceptionally strong individual to find ego stability in your own subversive existence while the rest of the world is telling you to hang in there and call when you’re better, normal, and ready to play.

In other words, until you are no longer biased toward societally sanctioned “sanity” you will necessarily experience chronic rejection sensitivity, since society’s message is that your world is not the real world, and, moreover, it’s not a sustainable place. You are basically instructed that your only acceptable narrative is “fight, don’t give up” — which certainly introduces chronic internal conflict among anyone whose goal is to learn to accept, manage, and find happiness within debilitation.

The spectrum of those most afflicted by this conflict would naturally change over time. E.g., not long ago cancer patients were pretty widely blamed for their sickness. Now, since cancer narratives have evolved, they are more likely to get less stingy support — but that support is still contingent on the temporary nature of the condition. You will either be urged to get back to normal ASAP, or comforted in your dying. Only a subversive would say, “relax, don’t fight it, you are perfect as you are.”

But those who are permanently ill, long term, — if they don’t want to succumb to neuroticism — are forced to discover and embrace their lives outside the mainstream narratives. Maybe the mentally ill are gradually becoming less prone to rejection sensitivity since interest in mental-health stories has blossomed in recent years (which means many conditions are no longer quite so “invisible”). But try taking a current survey of people suffering from ME, fibromyalgia, even MS, and I’ll bet the rejection sensitivity rates would be off the charts.

>There are various other traits everyone knows are linked – officially, hyperactivity and “behavior problems”; unofficially, anger and thrill-seeking – but most people consider these to be some sort of effect of the general attention deficit.

This is wrong, because that is just one kind of ADHD. For example, “absent-minded professor syndrome” is actually an important version. On /r/ADHD people mostly complain about things like misplacing their car keys or forgetting about important meetings or being either late or over-worrying it and going too early.

The point is this, Scott. The thrill-seeker has his attention grabbed by EXTERNAL phenomena, the classic “look a squirrel!”. The “absent-minded professor” has his attention grabbed by INTERNAL thoughts, and I think this will be more common and more well know in this intellectual community! People who are always somewhere else with their thoughts when you are trying to talk with them etc.

Similarly, hyperactivity doesn’t necessarily mean running around! For more passive, perhaps more intellectual types, it is things constantly fiddling, shaking their legs, chewing their pen or nails, or even just having racing thoughts. It appears more as nervousness, some psychiatrists may have a difficulty of telling it from anxiety, I think in my discussion with mine the key point was that an anxious person often shuts down in crisis situations why an ADHD person performs well because finally something interesting! The ADHD person is ususally bored, the anxious person not, but would like to be. The ADHD persons nervous vibrations are more like self-entertainment.

As for your study, Scott, try to put ADHD people into two categories: diagnosed as a child and diagnosed as an adult. According to my psych, literally everybody diagnosed as an adult also has depression because of having had too much shit to deal with, while someone diagnosed as a child has at least a CHANCE of not spending their childhood with adults yelling at them.

I have no data how strongly depression is linked to rejection sensitivity but at least there is a fairly obvious way how it could be: depressed people tend to think they are worthless, and easily see rejection as a confirmation of it.

Because you don’t have that diagnosed in childhood vs. as an adult data, try to see the correlation betwee non-depressed ADHD people and rejection sensitivity, I predict none.

A few thoughts on how SSC survey results could be consistent with continuing to talk about RSD in the context of ADHD (although a lot more accurately and carefully than now):

1. Even though RSD might not be helpful in figuring out exactly which psychiatric condition someone has, it might be a good enough proxy for neuroticism to be one of a set of questions to determine if someone has a psychiatric condition in the first place, and then other questions can be used to figure out whether the person has depression, ADHD, or anything else.

2. Even if RSD is not one of the distinguishing features of ADHD, it might be one of its facets most treatable by cognitive behavioral therapy, and so worth considering from that perspective.

3. I suspect a lot of people talking to a therapist about their anxiety or depression already discuss their sensitivity to rejection, because it seems an obvious part of the problem. With ADHD, the connection might be less obvious, so the problem might be more likely to be missed (even if it occurs less often).

4. It’s possible that SSC readers tend to self-diagnose, and describe symptoms to their therapist in a way that is (maybe unintentionally) consistent with a rational understanding of how a given disorder is defined. So someone who thinks they have ADHD identifies with all of defining elements of ADHD, and assumes that he is close to average on every other trait (so his prior belief about himself is based on a rational definitions of what he considers to be his labels, then he updates the belief a bit based on introspection). So an SSC reader with ADHD assumes that he is pretty close to average on RSD, because RSD isn’t connected to ADHD in his mind. On the other hand, an SSC reader with depression or anxiety is more likely to identify with RSD, because there it does seem to be part of the definition. On the other hand, a non-rationalist-inclined person might base his prior about himself on intuition, and not think nearly as much about the definition of ADHD, and might more accurately self-identify with RSD (without obfuscating his answers to survey questions with rationalization). So all that is to agree with Scott, that there is a chance that the SSC survey does not generalize, and that maybe in the general population people with ADHD are more prone to RSD than people with other psychiatric conditions.

5. Is it possible that people who have a diagnosis of ADHD are less “extreme” in their pathology than people with other diagnoses, because the diagnosis of ADHD and the medication have become so popular? So if you come up with some sort of single scale for each condition from 1 being fully functional to 10 being unable to do basic tasks independently, then a 5 with ADHD could have more RSD than a 5 with depression, despite the fact that the average diagnosed ADHD patient has less RSD than the average depressed patient (because ADHD is over-diagnosed, and the average ADHD patient is only a 3, while an average depressed patient is a 6).

>. I suspect a lot of people talking to a therapist about their anxiety or depression already discuss their sensitivity to rejection, because it seems an obvious part of the problem.

How are they supposed to know their sensitivity to rejection is a problem in the sense that they are more sensitive than others?

I mean, Freud defined psychatry as making abnormally unhappy people normally unhappy. Just because something sucks in my life it does occur to me to bring it up with my psych, because it may just be one of the gazillion things that suck for everybody. I need some clue that not everybody is like that to bring it up.

For what it worths, when I was younger my attitude to dating was very typically ADHD, I found most women boring because I find most people boring, but occasionally some trait meant “hyperfocus”, falling in love head of over heels. Of course rejection hurts in that case. Later on in my life I changed my model to “life is boring, for my brain, not other people, try to live a normal life and have a lovable SO even if she, too, bores you” and tried to overcome this i.e. talking with initially boring seeming women to see if I find something interesting about them later on. In that sort of a situation a rejection did not hurt.

Could that be summarized as: I don’t care if people I don’t like don’t like me?

At that point, it sounds like pre-entering a relationship as a chore. Is that something you really want? Alternatively, is being in a relationship with someone you find boring fair to the other person?

OTOH, I have the same problem with overweight women. As a fat, low-physical-attractiveness man, my dating life would be much easier if I didn’t find overweight people repulsive.

One of my pet theories is that atypical depression and social anxiety have some key commonality, as evidenced by interpersonal rejection sensitivity and positive response to MAOIs. The thing is, no one’s had to agitate to prove that it’s a feature of both because it’s really obvious that both groups tend to be really sensitive to interpersonal rejection. (Then there’s borderlines, but hey, pet theories aren’t supposed to be comprehensive.) Still waiting for a chance to start that MAOI.

They are available if you want to try them but medical oversight is generally advisable. Note the withdrawal symptoms from non-selective MAOIs, particularly irreversible ones, can be fairly significant and tapering is highly recommended on discontinuation.

I’ve never heard of the “Forer Effect” but have definitely noticed it in use and am perhaps guilty of jumping on board at times. I’m self-diagnosed ADHD without meds until last year actually and I’m almost 40. Rejection has often been a barrier in my life, I don’t think it’s quite as simple as described by Dodson though. I recently read the book “No More Mr Nice Guy” which goes into “Nice Guy Syndrome” and ties to childhood issues and felt this better-explained issues I’ve had with rejection more than ADHD alone. I’ve also had a few battles with depression and definitely felt far more susceptible to and out-write avoided situations where I might be rejected. I too don’t totally buy it. While at times rejection & fear are barriers to my life (simple things like calling people where I might bother them or fear of starting my own business and failing), other times I really don’t care what people think. If you asked me to wear an eagle costume and dance in a busy street I wouldn’t worry about rejection, maybe because I know that the rejection would likely be outweighed by positive reinforcement? I’m not sure. I often did outrageous things when I was younger and hated rejection but found it less powerful when padded with support. Maybe the fear of rejection forces those with ADHD to strive for more creative outlets because being “normal” means the chance of rejection is more likely to happen? I’m not sure about that either.

My risk-aversion and fear of rejection are similar to yours. In my mind, it's fine to dance in an eagle costume if asked, because anyone who objects is clearly the person with the problem, not me. On the other hand, if I bother somebody by calling them, then that's my fault; they were minding their own business until I demanded their attention. So there's a very deontological moral aspect of it to me, where I don't fear being *mis*judged but am afraid of being *correctly* judged as bad.

(Although there's also an issue where it's fine to dance in an eagle costume *if asked* but I'd never do so spontaneously. Not that I shouldn't, but I wouldn't.)

> If you asked me to wear an eagle costume and dance in a busy street

I would be overally nervous about being the center of attention (not the same as rejection) but I would probably just get drunk before and it would work, it always worked.

Big Five trait agreeableness is inversely correlated with income.

So in that sense, ‘Nice Guy syndrome’ is real. It’s important to stand up for yourself and to be assertive when needed.

This seems like the kind of thing that would be very vulnerable to, as they say, “seeing others’ highlight reels but your own raw footage.” You know how embarrassed you are when you screw up socially; you don’t know how others are impacted by their screwups. You see them being chill and brushing things off, while you feel yourself dying a little inside because you put your foot in your mouth. In reality, they are probably just as freaked out about their own performance as you are about yours. So, most people would probably say they are “more sensitive to rejection” because they simply see their own sensitivity, and they see others’ masks.

There is a practical problem – you have to know that you are more sensitive than others. I didn’t. I thought I was just of low moral character. However, given that those feelings respond to my ADD medication…

Why are you even giving the time of day to this bogus, made-up “disorder?”

What do you mean by made-up? I do partially agree. I believe it’s only a disorder because we cater to the center of the bell-curve of human behavior and genetic studies have shown it to be part of our evolution but I guess you could say that about any disorder. I also feel ADHD-like symptoms are prevalent among young people due to lack of quality sleep and overuse of technology. There’s definitely something there though.

Please you both take a look at the DIVA test for diagnosing ADULT ADHD. When reading it my impression was “shit my life would be entirely different if this was spotted when I was a child”. English form, PDF: http://www.divacenter.eu/Content/VertalingPDFs/DIVA_2_EN_FORM%20-%20invulbaar.pdf

From this I am deducing this is real.

It is NOT about kids being uninterested in math. It is about adults misplacing their car keys, forgetting what you told them five minutes ago and being somewhere else with their thoughts when you are trying to talk with them.

I am glad for you, that you do not have any such difficulties yourself. That merits some degree of gratitude, really.

I think there’s an error with the self-diagnosed data – you seem to have gained ~800 respondents. Maybe I’m missing something obvious!

The rejection sensitivity might be a byproduct of ADHD tendencies, but I subscribe to low arousal theory as the primary explanation of ADHD behavior.

I have disordered sleep similar to non-24; I’ve talked about it on my youtube channel. In my view, the hyperactive ADHD symptoms might manifest due to some kind of metabolic energy efficiency; stimulants, after all, raise BMR, and in ADHD patients they appear to calm the patient down. Further, exercise is extremely effective in helping ADHD patients, and hat is a lot of energy expenditure for normal people is not for ADHD patients.

What exactly does low arousal theory explain that ADHD itself does not? We know we are constantly bored, we know medicine that messes with dopamine tends to help, and hyperactivity is something you may misunderstand, it is not necessarily running around but more like nervous leg-shaking and pen-chewing, it is an attempt to entertain ourselves, not some kind of an efficiency.

About exercise. While from every other viewpoint lifting > cardio, it may be the other way around with ADHD as I am a lifter and it does nothing for it, while others in the ADHD support group I go to tend to go on hours long bicycling on country roads and suchlike.

ADHD appears to usually be associated with a weak ability to suppress activation of the default-mode network, resulting in excessive daydreaming and difficulty concentrating unless a situation is active or stressful enough to naturally increase levels of dopamine and norepinephrine enough to compensate.

Genetically, ADHD is associated with alleles that result in less responsive dopamine receptors particularly DRD4, as well as overactive dopamine transporter proteins and underactive enzymes for converting amino acids into dopamine and/or converting dopamine into norepinephrine.

Net result is that attention tends to drift more easily, ‘explore’ tends to outweigh ‘exploit,’ boredom tends to arise readily, and short-term memory and concentration tend to be impaired except under stressful or highly active circumstances.

As someone who started getting into psychology, I’d say >80% of the field is like this. Entire subfields based on the work of one PhD or another who has nothing in his work to justify thair claims and yet, since they started early, hundreds of follow-ups by different “researchers”, from conceited institutes, all just following suit. Worse is watching people being sent to jail because of the “research”.

The field has left me utterly disgusted, I tried writing papers on the problems I saw, but no support for it. Thankfully I left the field before getting the degree. I’m actually shocked Scott is in the field and hasn’t written anything about this kind of shit yet. I guess Scott is a psychiatrist as opposed to a psychologist?

Scott is a psychiatrist, yes.

I would have predicted that SSC readers would (really) be more sensitive to rejection than the population as a whole, so I am not convinced that we are seeing even a small Forer effect (though of course it’s possible).

Speaking of Forer effects, am I the only one who would answer “no” to quite a few of those questions?

Sure.

Yes.

I might say unproductively used rather than unused, but yes, and I think the empirical evidence for this is pretty overwhelming.

Nope. I’m atrocious at managing/working around my several personality flaws.

Disciplined and self-controlled outside? Jokes.

Actually, no. Not because I don’t sometimes do bad things or make bad decisions, but because I’m rarely if ever in much doubt about it.

Sure, I mean this one is really obviously near-universal, right?

Yes, but as with most people in this community I suspect this really is far truer of me than the average human.

Quite the opposite. I’m irrationally averse to being open with others, and have caused myself significant harm by being insufficiently open, while occasions where I have felt able to be open have almost always had positive or neutral results.

Yes, but overall I am pretty clearly more introverted than average.

Lofty, perhaps, but I actually think largely realistic.

Nope. Granted, I’m not entirely sure I know what security means in this context, but I can’t think of a plausible meaning that is one of my major goals.

Interesting point.

Possibly your rejection of some of the Forer statements hints at another flaw from having SSC readers as your sample – I would predict that SSC readers would be less susceptible to Forer effects than the general population. This would mean that not finding a Forer effect here or a very small one doesn’t rule out there actually being a significantly larger effect on the general population.

(I once went on a training course where we were given personality profiles from a questionnaire. I went through the results circling all the statements I thought were Forer effects, although I didn’t know the phrase at the time. I think my course mates thought I was a bit weird but that kinda illustrates my point)

Having a standard Forer statement in the questionnaire and comparing the result to other published results would be interesting. I have no idea if such a question was included in the survey – hindsight’s a wonderful thing!

I think some of us might find ourselves far more comfortable with functional routines, planning our variations out ahead of time so they’re still part of a pattern, and working within clearly defined and agreed-on limits.

I’d have answered no. I’m trying to have my life be as structured as possible, and I want change to be deliberate and controlled. You could argue that I do prefer a certain amount of change (I want to make progress) but that’s not how I would have interpreted the quesiton. I’d have answered almost all other questions with yes.

I agree with you on contradicting some of these.

3. You have a great deal of unused capacity which you have not turned to your advantage.

Not really. I think I’ve reached my limits of achievement. They’re not amazing, but I’ve hit them.

5. Disciplined and self-controlled outside, you tend to be worrisome and insecure inside.

Hahahahahahahahaha no. I definitely don’t look like I have my shit together. At least, I don’t think I do.

7. You prefer a certain amount of change and variety and become dissatisfied when hemmed in by restrictions and limitations.

Hell no. I want to have a blissful unchanging life with every single day the same blithely fun day. Seriously. I’m not joking. I can’t stand any kind of change at all.

8. You pride yourself as an independent thinker and do not accept others’ statements without satisfactory proof.

Actually, I tend to believe people unless they or their statements strike me as sketchy. Life’s too short to be paranoid or constantly doubt people on stuff.

9. You have found it unwise to be too frank in revealing yourself to others.

I wear my heart on my sleeve and know I can’t change that, so I embrace it. Everyone knows most things about me, who know me.

11.Some of your aspirations tend to be pretty unrealistic.

No, those were beaten out of me by life in my early 20’s.

How do your precommits work? I’m pretty comfortable trusting that you precommitted to releasing this analysis regardless of the results, but that’s still a strong statement to make. Are they published somewhere? Maybe a published but unshared SSC post? Presumably they had to be hidden until the survey was done, and some probably from people taking the survey in the future, so I’d imagine it’s a bit complicated logistically.

IIRC, he posted a set of precommitted hypotheses after the survey closed, but before he started analysing them properly.

Here, though that doesn’t seem to include this topic.

There are two separate issues: how many topics he will consider and whether he will publish null results, vs multiple definitions within a single topic. It’s easy to count the number of studies and adjust for multiple comparisons, but “the garden of forking paths” refers to how it is difficult to count the effective number of comparisons in a single topic. So committing to an operationalization on a topic may be more important than pre-registering a list of topics.

I have less than 10% confidence this is a real effect and not just a survey issue.

The survey question requires self-evaluation with respect to a population. Furthermore, a common symptom with ADHD is difficulty with social relationships (especially romantic, i.e. the kind that explicitly involve rejection or not-rejection every time). How many survey participants need to mis-read the question as “I have more difficulty with rejection” instead of “I am more afraid of rejection”. Hell for that matter, even if you correctly read the question, how do you respond if you (let’s say for the sake of argument, with perfect accuracy) know that you personally get rejected more often than other people. Would it be correct to say you have more fear of rejection if you have a higher expectation of being rejected per social relationship?

Also, how many people really talk about their fears of rejection? Maybe with a very small number of very close friends/family.

I don’t talk with my current SO about the years of relationship struggles and anxiety I had before we met. Meanwhile being in a fairly strong relationship, I have basically no fear of rejection right now. I’m not concerned with it because I’m not pursuing new social relationships (I am, but none that are particularly important).

I’m also ADHD diagnosed. I’d certainly say that I have experienced serious anxiety related to rejection in my life… but more than is typical? That’s extremely difficult to judge and I’m a geek who reads SSC (probably not stupid, I hope).

So yeah, I hate to be a pessimist but I suspect this survey isn’t worth the paper it’s printed on.

I think it’s an interesting question how one distinguishes between “I’m more emotionally sensitive to rejection” and “I don’t think I’m very good at relationships because a lot of partners have expressed frustration at me.”

In my practice, adults with ADHD often show up because partners have pushed them to because they’ve run out of patience with their difficulty following through on life logistics and showing up attentively in the relationship. After a person with ADHD hears that a few times in significant relationships, it’s understandable one would internalize a story of “I’m likely to be rejected if I don’t do better than I’m doing now.”

I know some people with ADHD have heard criticism from bosses, co-workers, parents, friends, and partners for years. It strikes me as inaccurate to read whatever frustration the person with ADHD feels in response to this criticism as “emotional sensitivity to rejection.”

Which I guess is a long-winded way to say that I suspect a big part of what Dodson may be reading as sensitivity to rejection is instead an effect of living in a world that has narrow limits on “normal” behavior, rather than it being an inherent feature of ADHD. That’s why I find the Big Five personality trait correlations to be instructive — you’d expect to see more neuroticism among people with ADHD if emotional reactivity were a built-in feature.

Alright, my comment seems to be auto-removed because I have a new account and I included some links. I wrote a somewhat shorter version without links, because the discussion has started. I am also not sure if the comment exists anymore, because I used to see it after posting, but now it is completely gone.

1) The term RSD makes it seem like it’s only Dodson’s thing. However, if you assume that RSD is just an instance of more general problem with regulating emotions, then there are other people talking about it.

Here is a quote from Thomas Brown:

It seems like Dodson may exaggerate the importance or prevalence of RSD and focusing on it way too much, but it seems to me that emotional dysregulation is a problem for a lot of people with ADHD.

2) Scott makes it sound like Dodson’s treatment is completely at odds with what other people do.

Scott writes:

Dodson suggested treatment is guanfacine or clonidine. I have barely any understanding of neuropharmacology, but I think they are alpha2 receptor agonists (i.e. not alpha blockers, which are alpha receptor antagonists). Correct me if I am wrong, but I thought agonists and antagonists are very different.

Anyhow, both guanfacine and clonidine are FDA-approved treatments for ADHD (in kids). Both are not the first line treatment, but it does not seem all that crazy to add another known ADHD medication to a stimulant.

3) I actually started taking Intuniv (modified release guanfacine) a couple weeks ago (in addition to a stimulant). It seems to be working really well. My emotions feel less raw, I have less anxiety, I am less impulsive. For me it works really well so far, but I am suprised that almost everyone on reddit was meh about it. Could it be a placebo effect? Or maybe it is just initial effect that goes away?

The major reason I am confident it IS part of ADD at least some of the time is that, like you, I’m significantly less emotionally sensitive when I am medicated. I don’t take things as personally, and what I do take personally I’m much more able to shrug off.

Anecdotally, guanfacine does seem to help a bit for me, and tends to be rather anxiolytic as well. I just keep forgetting to actually take it.

It was a weird experience seeing how much I very much wanted ADHD to include rejection sensitivity. As someone sorta with an ADHD diagnosis (I’m prescribed adderall but original for depression and my doctor felt it was probably treating ADHD as well) and very very strong rejection sensitivity (as in being afraid to go in shops in Israel lest someone be offended I don’t speak Hebrew despite them all speaking english) it would have been a nice explanation and given me a better way to seek treatment.

Right now I’m quite worried about mentioning rejection sensitivity/anxiety to doctors because I’m afraid that they will blame the adderall and make the ADHD/depression worse when in fact it works to reduce that sensitivity. It would have been nice if they had been linked but your points are pretty convincing.

Surely MAOIs and stuff like that is incompatible with adderall. Are there any worthwhile treatments for this that are compatible with adderall (the risk/reward ratio for raising the issue is surely negative if there aren’t any). In my experience SSRI’s aren’t worthwhile for me.

Have you considered trying modafinil? It has a rather different effects profile from classical stimulants (adderall/ritalin) and I’ve heard that it’s better for anxiety. I don’t have anxiety, so I can’t report personally, but it works well for my ADD.

In theory, how would one go about obtaining some?

Depends on where you live, really. In India you just go to a pharmacy and buy it.

Prescriptions might be hard to get, because if it’s not prescribed for Narcolepsy, it’s off-label and few doctors will be willing to try it (often because of incentives of the insurance system). Otherwise black markets are detailed and provided with verified Onion links on the clear net site ‘deep dot web’. Some sites also just sell the stuff on the clearnet. These are specialized just for Modafinil, and seem to fly under the radar, imo because of all the energy of law enforcement being taken up by sexier, scarier drugs. Gwern.com has an overview about vendors and buying in his Modafinil thread, which is 5 years out of date, but gives you a good sense of how the market works.

My impression is that, Armodafinil (100% R isomer (think Hollywood-pirate to remember name)) is better in every way than normal Moda (50/50 L and R).

I’d just like to add, if your GP won’t prescribe you a drug on request after you calmly explain your well-researched reasons for wanting to try it, GET A NEW DOCTOR. Balance out those incentives.

OTOH, US modafinil is super overpriced, even with insurance.

There’s a fairly active grey market in it, and Don_Flamingo has given details on that.

I got a prescription from my doctor (basically, I just asked, but a lot of people report having trouble), and I’m paying out of pocket for the stuff through Costco. For various reasons, that turned out to be my best option financially (I was previously on Concerta, but switched for several reasons), even when you include the Costco membership (there isn’t one near where I live).

DF means gwern.net, not .com

R-modafinil has a theoretical advantage, which is that it isn’t contaminated by S-modafinil. But all evidence points to S-modafinil being harmless. All other differences are due to arbitrary packaging decisions. The doses for R-modafinil are larger, which is a disadvantage for most people. R-modafinil has the advantage of correctly reporting the half-life at 16 hours, while mixed modafinil lists the useless statistic of the mixed half-life.

Fl-modafinil is also fairly decent, although I find the effects to be more skewed in the direction of a eugeroic than a dopaminergic stimulant per se.

Personally, I find that it feels subjectively much smoother and less prone to derealization than ordinary modafinil, with fewer side effects in general.

It’s in late clinical trials for ADHD currently.

Vendors do sell it already, though this can be a grey area depending on your national laws.

Dodson suggests guanfacine or clonidine. Scott makes it sound like it is completely weird idea. However, both are approved by FDA for ADHD (in kids). They can definitely be combined with stimulants and can actually reduce physical side effects of stimulants.

Combining two different ADHD medications is not a weird idea. For example, Russel Barkley (one of prominent ADHD researchers) seems to think it can be a good idea to combine stimulants and atomoxetine (Strattera) or stimulants and guanfacine (Intuniv) to get a wider coverage of symptoms (this is unrelated to RSD).

I’ve been taking Intuniv (modified release guanfacine) for a couple of weeks. So far it works really well, but it’s only been a couple of weeks and it is hard to tell how well it is going to work long term.

I had a similar reaction. This post was the first time I had encountered this connection being made but I was immediately a bit invested in it being true.

I was diagnosed with an attention disorder as an adult about a year ago and treatment has been life changing.

But I have also had an unusually high aversion to social rejection my entire life. As a result I isolate a -lot-.

Although, unlike you, anxiety has been almost completely absent since treatment (I had a lot earlier in life).

And there has been a bit of a boost socially, which I attribute to there being less of a mismatch between my self-concept and my behavior (i.e. consistently having productivity goals and never following through with them is pretty terrible for your self worth).

This sounds very familiar.

Non-selective MAOIs are dangerously incompatible with stimulants, especially monoaminergic releasing agents like Adderall.

Selective MAO-B inhibitors can be fairly safe at low doses, e.g. selegiline at less than 5mg/day, but individual sensitivity can vary and close supervision may be required.

As an alternative, perhaps consider guanfacine or clonidine? I found clonidine caused sedation and overly intense rebound symptoms if I missed a dose, but guanfacine worked well for both mildly improved focus and decreased anxiety.

The sensitivity to rejection could also be what I would like to call “individualism”. I have 3 kids, 2 were identified as ADHD and one was not.

The two that are ADHD were not very social in 3d grade, tending to stay in their shells, preferring to wander around at recess making bloop-blip noises or playing alone (they were both later identified as gifted and currently are mostly in the nerd clan). The other kid is the team player, does not get chosen last on the playground, hangs with jocks and preps and nerds, is very bright but not “identified” as gifted.

With these 3 data points, the two who are not team players are the ones who got flagged by the teacher as worthy of medication. Maybe they were afraid of rejection, or maybe the K-12 system does not like square pegs.

Thoughts?

Among the ADHD folks I’ve worked with, I don’t see rejection sensitivity, as I do with people who have anxiety, depression, BPD, interpersonal trauma histories, etc.

Among people with ADHD, I do see that often they’ve experienced a lot of shaming by others across the years — being told they’re lazy, underachieving, selfish, etc. And so they very often have internalized these judgments and express both defensiveness and shame about not being able to function better in the world. That’s a really different animal though from rejection sensitivity, which manifests more like how we see it with people who have borderline features.

Rejection sensitivity is a “neurotic” trait in the big five, and while high neuroticism is associated with all kinds of mental disorders, my perception is that people with ADHD are by and large less neurotic than people with other disorders.

I would think that rejection sensitivity is most highly correlated with anxiety (and depression perhaps equally so?). I don’t know what the data is on comorbidity between ADHD and anxiety, but I’d guess it’s less than with other disorders.

I have read a bunch of stuff suggesting that people are sometimes misdiagnosed with ADHD when they have trauma history, and trauma history can produce rejection sensitivity. But my understanding is that that’s a confusion over whether inattentiveness is instead a kind of dissociation and impulsiveness a kind of maladaptive coping mechanism for painful emotions. So to the extent Dodson’s arguing that ADHD includes rejection sensitivity I would think he’s misattributing ADHD to people with trauma histories.

My random clinical experience tells me that avoidance is a pretty strong behavior among people with ADHD as well as people with anxiety and depression. The thing that seems different among people with ADHD is that some portion of what looks like avoidance is disorganization/forgetting, while the people with anxiety disorders seem to be actively avoiding and feel guilty about it, rather than feeling guilty about having forgotten to do something.

Would be interested to hear about other people’s experiences.

Just looked at a few studies on ADHD traits and Big Five personality traits and there seems to be significant correlation between ADHD and low conscientiousness (inattentive) and low agreeableness (hyperactive). Higher neuroticism is only weakly correlated it seems — I don’t have the data to compare, but my guess is more weakly correlated than neuroticism is to anxiety or depression.

Most of the test items for neuroticism in Big Five personality tests ask about emotional reactivity in interpersonal settings. It seems to me if people with ADHD were significantly more sensitive to rejection than most people, that it would show up in these studies as a strong correlation to neuroticism. The studies on neuroticism and other mental disorders besides ADHD are unequivocal.

A study on comorbidity of ADHD and anxiety disorders shows up to 25% of people with ADHD also have an anxiety disorder. But that figure is the same in the general population, so it seems having ADHD doesn’t necessarily make one more likely to have anxiety — but it will change how the person presents overall. It’s possible Dodson’s view is skewed by more contact with people who have both ADHD and anxiety?

Among people with ADHD, I do see that often they’ve experienced a lot of shaming by others across the years

This may be related: my first thought when I read “adults with ADHD are more sensitive than usual to rejection” was that a potential confounder is that young people with ADHD may in fact suffer higher rates of social rejection, rather than merely being more sensitive to some common baseline. (I may or may not have personal reasons for thinking this.)

Yes, this is a really good point that cuke made. I think we’ve all heard the old trope that you aren’t paranoid if people really are out to get you. This could well be a similar effect.

I wish there were enough schizoids to appear on those graphs.

Reminder to SSC readers: if you didn’t think Unsong was weirdly lacking in characterization, you might be a schizoid!

Wait, wait, so all of the deleted comments on Reddit are archived at this other site, and you can still read them there? *mind blown*

Yes. The internet never forgets.

There are sites where you can bulk-download the whole of Reddit by month, if you hate having unused hard drive space. Might try to shove some of it through some kind of ML someday.

Honestly I only learned about this site while working this comment. But I just assumed something of the sort existed, so I googled “read deleted Reddit comments” and there it was.

@Toby Bartels

Not all comments are archived, as they are periodically retrieved. So it depends on how quickly the comments have been deleted.

Or you might be able to empathize with people in the Berkeley rationalist community, who knows?

Sure, sure… but maybe just take a peek at the DSM criteria? :p

(my agenda here is that I’m actually really glad to have learned about SPD and think others would benefit as well, but think the claim about Unsong is a little much)

That looks like the first twoish symptoms of dysthemia (aka chronic depression) broken up and focused on social impacts. The Unsong claim is frankly ludicrous. “I didn’t like this thing someone made, it must be the product of a personality disorder” is a claim I’m never going to take seriously in respect to anything.

At the end you mention a statistically significant difference. Not that I doubt you, but you don’t present anything that would let me see that anywhere. Could you show confidence intervals or p-values or something? CIs in particular on the difference between ADHD and gen pop would give me a much better sense of magnitudes of uncertainty here.

Is rejection sensitivity a diagnostic criterion for anxiety disorder? It seems like it might be, and probably should be (based on your results).

“I am more sensitive than others to rejection, teasing, criticism, or my own perception that I have failed or fallen short”

A general question not about your findings: The questionnaire frames it “than others”. How would you find out what the typical level of rejection anxiety is?

Teasing is a special case, since some teasing is evidence of acceptance– which doesn’t mean everyone is comfortable with it.

I agree it’s super likely to yield false positives but I think those of us who find rejection sensitivity causes us to avoid normal activities and other standard behaviors can have good behavioral evidence.

A better question would be phrased in terms of external behaviors since everyone feels they experience more internal suffering than others.

Indeed, although the gender roles tend to result in more negative consequences for men if they seek commiseration or if they avoid situations where they may/often fail, so men and women seem to use different coping strategies on average.

It seems to me that the existence of several different coping strategies makes it hard to ask a single question and get something that is comparable. So perhaps you need to ask four different questions:

– Have you decided not to do something in the last week (or month) out of fear of rejection?

– Have you sought emotional support for a rejection that happened to you in the last week (or month)

– Have you taken any action in the last week (or month) to reduce how often you are rejected?

– Did you try not to take it personally when you were rejected in the last week (or month)?

Although these are still somewhat mediocre questions and you may need more detailed questions.

As someone with ADHD who hasn’t heard of “Rejection Sensitivity”, the concept seems really nebulous, and trying to combine it with ADHD which is also less than well defined seems especially fraught. Though I must say that I have at least some interest since I could be argued as to having greater than normal fear of social rejection (My profile name is actually a reference to the fact that I don’t like using forums for fear of not being accepted).

what about the confound of the people with ADHD who got distracted and didn’t finish the survey

Were people with particularly rejection-sensitive-dysphoric ADHD disproportionately likely (among the population of people with ADHD) to fail to complete the survey?

If not, it wouldn’t affect the results, just knock sample size down a little.

just making a little ADHD joke

I chuckled.

Ugh. I can’t see my comment with a few links. I wonder if it is completely lost or just in limbo waiting for approval (I have a new account).

Potential confounder : anxiety as self-surveillance.

People with ADHD may be aware of the potential consequences of impulsive actions, and may worry about those consequences. This may manifest as an increase in generalized anxiety (in those susceptible). The increase in generalized anxiety may serve an adaptive function, as it replaces or supplants their lagging or diminished ability to self-surveil prior to action.

So maybe it’s not that people with ADHD have rejection sensitivity as a core feature, but instead, it’s that turning the dial up on anxiety is how some people with ADHD manage their impulsivity.

And that might not even be reliably detected in your survey, if the level of anxiety required to counterweight impulsivity is more-than-normal-but-not-quite-GAD, or, if the only people implicitly pursuing this strategy are those who are able/susceptible, independent of their ADHD.

But IANA[behavioral health specialist].

This hits surprisingly close to home. One of the things that I noticed about starting meds is that I was paradoxically a lot calmer, despite also being diagnosed with anxiety. It turns out that I can be a lot more relaxed if I’m not going to be worried about what inane thing I’m going to say.

Also, I suspect that a good amount of my dating problems is/are related to women picking up on my anxiety empathetically – it’s hard to trust someone if you are getting that creepy vibe or are scared.

Wouldn’t this just be capturing high trait neuroticism of the Big Five Theory of Personality. From a Cybernetic Theory of Personality point of view Adhd is low trait conscientiousness. Even further, it would seem to be high neuroticism with high agreeableness(being cooperative and wanting to please others) and that would lead to extreme sensitivity to rejection. I find Dr. Dodson to be way to loose with how he describes Adhd. The go to for understanding Adhd is Russell Barkley, by far. It is not the APA they are too narrowly focused on working/non working memory and not the other executive functions. Again, think about this in terms of low conscientiousness; very high discount rate, low self-motivation(non evaluative performance), poor impulse control,(not checking social-media), etc. Low dopamine means low approach motivation to your goals due to a lack of ability to filter out all that gets in the way of moving toward your goals.

Just out of interest: are you controlling your results for multiple comparisons? Digging through your treasure-trove of data, there’s likely to be at least one spuriously-significant result, unless properly controlled for.

Also, I think it’d be interesting to look at rejection-sensitivity between men and women. I realise you can’t do that retrospectively, but it might be interesting to design the next data collection with this in mind.

The reason why I think it’s be interesting is because it would fit with the empathising-systematising axis (where emphasisers would be more likely to experience rejection-sensitivity to systematisers—although I admit this is just my intuition, which isn’t very scientific). However, on the other hand, youd expect rejection-sensitivity to correlate with depression—which, in my understanding, should be evenly distributed between the sexes.

Working in a corporate context, I’m constantly exposed all manner of pseudo-scientific management theories and ideas—which have little empirical backing. One of these is the constant harking that ‘women suffer more in the workplace’, which I (as a woman) find both sexist and patronising. I’ve tried to find studies measuring depression prevalence between the sexes (professionally and domestically) to stand up for men’s right to struggle in the workplace too (which I think would create a more empathetic workplace for everyone). It seems to me that the latest research suggests there is no difference between the sexes in depression prevalence (generally), and it would be cool to find if this is true also of other conditions—like rejection-sensitivity.

I think we need more work showing that men have an inner life too, since a lot of the contemporary narrative casts men as unfeeling automata of the patriarchy, which is nonsense.

I believe preregistration (which is more or less what Scott did) makes this unnecessary. The multiple-comparison control is to make sure you don’t go digging through the data to find the spuriously-significant results, but if you say “here are the comparisons I’m going to do” ahead of time, then the only relevant result is the single chance of you hitting something spurious on that one, which normal significance testing handles perfectly well.

From where I’m sitting, you seem to have some very strange notions about data analysis. For one, multiple comparisons are not an issue when the analysis is preregistered and sufficiently theoretically motivated. To do otherwise would (a) penalize more complex designs and (b) ultimately mean researchers need to guess how many NHSTs they’re going to run across their entire career and adjust accordingly.

Particularly, in this case, by my count there were 5 preregistered tests, and a sanity check on participants selected according to a different criterion (self-diagnosis). When I do that (typical minding Scott here), I don’t care one bit whether the pattern of dots-and-not-dots repeats between both samples, especially when sample sizes differ. What I care about in these cases is the pattern, which in the present case is indeed highly similar, which in turn increases my confidence in the findings.

Mindlessly counting comparisons here would lead careful researchers to restrict themselves to only include the alternate single diagnosis with the most participants and drop either the self or professional sample for a total of 3 (ADHD vs. control, ADHD vs. single other diagnosis, ADHD vs. multimorbidity) instead of 10 preregistered comparisons. How would this be an improvement over the present analysis? I see only downsides.

All this, without even going into meaningful effect sizes and what the sample size allows one to demonstrate.

Second, of course he can analyse by sex retrospectively. Whyever not? The analytic strategy he decides on before or after the data come in is not something magical that affects the results (aside from experimenter effects). What he can’t do (and got nowhere near doing) is analyse by sex out of curiosity, then turn around and claim the p-value is definitve proof one way or the other. And the reason isn’t that the hypothethical effect wouldn’t be there in his data, but that the analysis ‘by sex’ is one of many possible analyses and if all of those are done, then there is indeed a high chance of spurious results. So any finding ‘by sex’ would be exploratory, generating hypotheses for the next data set.

At the same time, theoretical motivations for sex differences in rejection-sensitivity are easy to come by and I’d be happy to accept tentative results. What would limit my belief in them isn’t pregregistration or not, or the exact/adjusted p-value, but the nature of the SSCS itself. I have no notion how the combination of SSC-readership and self-selection for participation impacts results, which in turn means any generalization to the population at large might be a wild over- or underestimate from where I’m standing.

Apologies if that comes across a bit strong, but IMHO Scott’s analytic strategy here is excellent and if even half the papers currently published in the empirical social sciences where this scrupulous there wouldn’t be a replication crisis.

Sorry, but I think you’re wrong. Even if your study is pre-planned, the risk of producing spurious false-positive results still exists (specially if your p-values are anywhere near 0.05—in which case one in every twenty tests is likely to be a false-positive). See, for example:

http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/514/417

(And I quote):

Also, this one never gets old: https://xkcd.com/882/

Regarding your second point, unless I’ve misunderstood something, post hoc data analysis isn’t completely kosher. This article provides a (clinical) discussion : https://www.ahjonline.com/article/S0002-8703(98)70116-4/fulltext

As it discusses, sone types of subgroup post hoc analysis might be justified, but it does create problems with multiple comparisons—which will need correcting.

I don’t profess to being an expert on statistics (I really don’t), but I do agree with you that what Scott is doing is laudable. I guess I should just accept he’s trying to do the right thing, apologise for being curious, and retreating out of this thread. I might well be wrong, and if I am, please provide me with links where I can remedy my ignorance, since I don’t like being wrong.

Before doing so, I should clarify that what I thought was interesting about the gendered pattern of depression (to which I intuit that rejection-sensitivity might be important) is because I have t seen much discussion of the condition being equally distributed between the sexes—the prevailing wisdom seems to suggest that women are more likely to suffer from it than men, which I don’t believe, and I think it would be interesting to have someone like Scott discuss this in a bit more detail, since it’s an interesting topic.

I don’t think they’re talking about quite the same thing. You’re right in that doing 20 tests that you preregistered doesn’t magically mean the one that does turn up as significant is real and not an artifact. But there’s about four preregistered tests here, not 20, so the chances of one being spurious is a lot lower.

That’s still not a reason not to control for them, don’t you think?

Roughly how were you proposing to control for them?

Wouldn’t it be better to look after the fact and ask what the chance was that the preregistered results would have happened had the null hypothesis been true for all of them? And if that chance is really low, say that there is no real need to do anything about it?

I see where you’re coming from, in that we could preregister all 20 jelly bean trials and then point to the one that worked, and say that preregistration means we don’t need to correct for multiple comparisons. But the point of that correction is to control for fishing expeditions, where you throw a bunch of data at the wall and see what sticks. That didn’t happen here. Doing 5 prospective tests pretty much removes you from fishing expedition, and his sample size is large enough that significance is a given with the sort of numbers we have here. Scott has previously said that he doesn’t give numbers on this kind of stuff these days is because he gets dragged through the mud by the anti-p-value/alternative statistics crowd.

The issue isn’t with the number of comparisons but with the fact that (1) there’s a specific mechanism of causality identified by the authors that is being tested and (2) they’re pre-registered.

The idea is that each hypothesis should have the nominal Type I error rate (5% if you’re using an alpha of .05). But you should make a point of identifying your hypotheses clearly. In this case, I think Scott did that for some of his comparisons but not others. His methods section stated:

In my mind, it’s appropriate to use the nominal alpha level for the first comparison only. This is a clear hypothesis that he’s interested in testing and a test he was going to do regardless. There’s a clear mechanism identified earlier for why he would expect a non-null result. I would consider adjusting for multiple comparisons because you look at the self-diagnosed and professionally-diagnosed populations while asking the same question. This looks a lot to me like getting an extra “bite at the apple”, and thus a Bonferroni comparison would be appropriate.

The comparisons against other conditions and the “multiple conditions” bin should be candidates for a multiple comparison correction. There’s no clear mechanism for why we would expect any of these conditions to be linked with RSD, and from what I could tell, you were just looking to see if anything interesting popped out. Even if you decided beforehand that you were going to look and see if anything interesting popped out, you should still do the correction. This is closer to exploratory analysis than testing a clearly defined research hypothesis that you’re interested in. Or at least that’s what it looks like to me; Scott should feel free to correct me if I’m wrong. As an aside, I’m not sure whether Bonferroni or Tukey’s method would be better for multiple comparisons correction here. If you were comparing all means against each other pairwise, you’d want to use Tukey, but since you’re only doing some, Bonferroni might actually be kinder.

I highly recommend anyone interested in why multiple comparisons are important read Gelman’s “Garden of Forking Paths” (and other associated papers). It’s clearly written and accessible to non-statisticians. It’s what I point my colleagues to when they have questions about this type of thing.

I don’t think this is at all true. Let’s say we only have the ADHD and normal bars in the graph. What have we learned? That those with ADHD have higher rejection sensitivity. Sure. But we haven’t learned how big that gap is, and how serious the issue is. It could just be because ADHD people tend to be more mentally abnormal in general. By comparing the ADHD with the depressed, we learn that this is indeed the case.

Here’s what Scott said about his method above:

And prior to that, here’s what he said about connections between ADHD and other conditions:

So when I say:

what I mean is that Scott didn’t make the case that RSD was linked generically with psychiatric disorders nor with the specific ones that he tested. Thus, a multiple comparison correction is probably appropriate, since which tests he did was contingent upon what data he ended up getting (ie the conditions participants in his survey reported having been diagnosed or self-diagnosed with).

Note that he could’ve just done the test comparing “ADHD” with “None” and been consistent with the hypothesis he half-proposed when discussing the other study.

Having said all that, I don’t think I anywhere stated that he shouldn’t have done the test itself. Post-hoc or exploratory analysis is totally fine, but it needs to be understood for what it is, and hypothesis testing becomes kinda weird in that context. I’ll again recommend Gelman’s “Garden of Forking Paths” as a good reference explaining why researchers acting in good faith can still end up getting spurious results.

The p-values are very far from .05, which is why Scott isn’t reporting them. For every analysis in this post and most analyses he does with the survey data there is no danger of sampling error, no matter how many comparisons he does. He emphasizes effect size because that matters.

Concerning your first point, I have already mentioned that the logical extension of that is to correct for all p-test a researcher will do over their lifetime. Since no one is advocating this, I conclude the argument is bullshit. Similarly, by that count, if a researcher uses 20 separate samples of jelly beans, one per year, there’s apparently no need to correct anything, since it’s always just one test.

So consider me highly uninpressed that you manged to dig up a ‘purist’ on this. They’re not rare. Frane himself may be a nice guy and well intended, but his article belongs to a kind og statistical tut-tuting on principle that I absolutely loathe. He both points out and then purposefully ignores that ‘no correction for pre-planned hypothesis tests’ is a heuristic, not a statistical rule. As any heuristic it is a generally sound rule, that incorporates a lot of underlying complexity (about sample size, alpha adjustment, FWER, FDR, and the fact that we usually know H0 is wrong, so p(data|H0) is pointless) into a simple rule that is not always correct. The article then pretends to have discovered this (i.e. that the rule is not always correct) and admonish the community for insufficient purity while neatly skirting the complex questions that led to the formulation of the heuristic in the first place.

bean below put it best IMHO: The point is to avoid fishing expeditions. If theory is so weak, that 20 hypotheses seem plausible, then sure, correction for multiple comparisons is warranted (better still, ignore p-values, report effect sizes and treat the whole thing as exploratory). But if there’s a sufficiently constrained theory, then multiplicity correction is just empty virtue signalling. In the section of ‘things that could invalidate the results’ it’s not even worth mentioning.

Regarding post-hoc data analysis: It is completely kosher, provided you admit it. If you read anything else, they’re wrong, or you misunderstood. It’s as simple as that.

There is debate about the use of p-values in post-hoc analyses, with strong arguments that they shouldn’t be used at all. For myself, I accept ‘descriptive p-values’ because my inner stats purist recognizes that they’re just encoding an effect size per sample size ratio despite my misgiving over the inevitable connotations of ‘hypothesis testing’ p-values bring and which IMHO are inapproriate here.

Then again, there are rare but legitimate cases where someone comes to a data set ‘blind’ with an interesting hypothesis and if they had hired a lab to collect data for this hypothesis we’d praise them for avoiding experimenter effects, but if the data already exists we suddenly say they can’t use it to _test_ their hypothesis, sorry, no p-values allowed. Statistics isn’t much help here, the pragmatic solution is to avoid the waste of a second data collection, let them run their tests with their p-values, attach a ‘but post-hoc’ to the limitations section and provisionally accept the result until another data set becomes available.

The section you quote has to be read in the context that doctors (of medicine) often are interested in all manner of subgroups in a dataset for valid clinical reasons and their biostaticians fight a often losing battle against another and then another and then another unadjusted subgroup analysis on the same dataset.

But here again, the best approach is usually not to correct everything into insignificance following the purists, but thinking carefully about what subgroup analyses are legitimate parts of the original research question, which are fishing expeditions/forking paths and the treat the results accordingly.

I agree with most of this. I put together a talk once where I tried to explain to a bunch of STEM PhDs some of the more useful non-technical lessons from statistics, and I had a slide titled, “Statisticians take p-values less seriously than you do.”

It’s a weird phenonmena, but I think you see it pretty generally where someone or some group develops an interesting-and-useful-but-flawed-and-not-universally-applicable metric or tool. It works pretty well, so it becomes widely adopted (at least within some subpopulation), but most of the folks who use it treat it as a black box. The result is that most users of this tool or technology don’t understand it thoroughly and thus attribute utility and authority to it beyond what it actually has.

The other example I used in my talk for this was sports analytics, where things like WARP (baseball) and PER (basketball) are better than traditional metrics and being single-number-summaries of success but still have clear flaws or biases. Folks who want to be “analytically savvy” but don’t actually understand the metrics thoroughly tend to be much more doctrinaire and vulgar when comparing players using these tools whereas the folks that actually built them understand when they’re good to use and when they might be missing something.

Matthewravery, I’d love to see the talk or the slides from it. Are either online anywhere?

(I can’t reply to your comment specifically for some reason, hopefully this’ll work)

While there is probably a meaningful answer about whether depression is evenly distributed between the genders (chronic unhappiness/anhedonia is a clear criteria even if hard to measure) I doubt there is a meaningful fact about whether rejection sensitivity is so distributed.

There are clear results that men and women differ significantly in terms of socialization strategies, how they process criticism/antagonism (direct confrontation or not) etc. (both biological and social). So how rejection anxiety is distributed between the genders will depend hugely on how exactly one draws the lines and there is no principled basis to choose how to weight the various behavior features in the diagnosis.

For instance, how do you rate reluctance to ask for help from others? That will surely vary between the genders.

I remember when a major theme of feminism was that men also have emotions, like women do, but are forced by sexism to repress them.

If you're working in HR, I hope that you're pushing for policies under which it ultimately doesn't matter whether depression is evenly distributed or rejection-sensitivity is not. Whatever the statistics, people are also ultimately individuals, and both women and men are going to struggle. I quite agree that recognizing this will create a more empathic workplace for everyone.

@Toby