Nobody likes that the US has the highest (second-highest after Seychelles?) incarceration rate in the world. But attempts to do something about it tend to founder on questions like “So, who do you want to release? The robbers, or the murderers?” Ending the drug war would be a marginal improvement but wouldn’t solve the problem on its own. And I’ve had trouble finding other ideas that engage with the reality that people are going to prioritize safety over reform and anything that significantly increases violent crime is a likely non-starter.

This was why I was interested to read the scattered thoughts in the effective-altruism-sphere about bail reform.

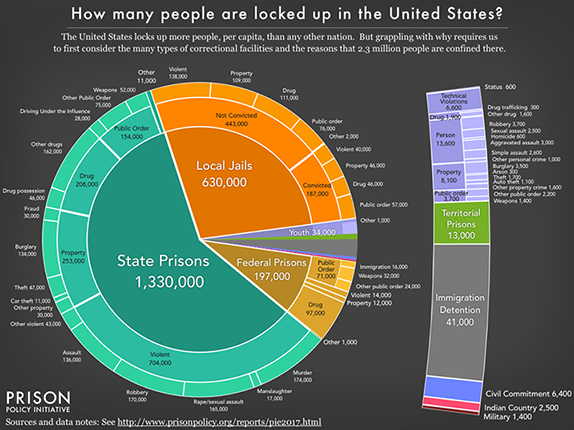

(source)

About a fifth of the incarcerated population – the top of the orange slice, in this graph – are listed as “not convicted”. These are mostly people who haven’t gotten bail. Some are too much of a risk. But about 40% just can’t afford to pay. They are stuck in jail until their trial, which could take a long time:

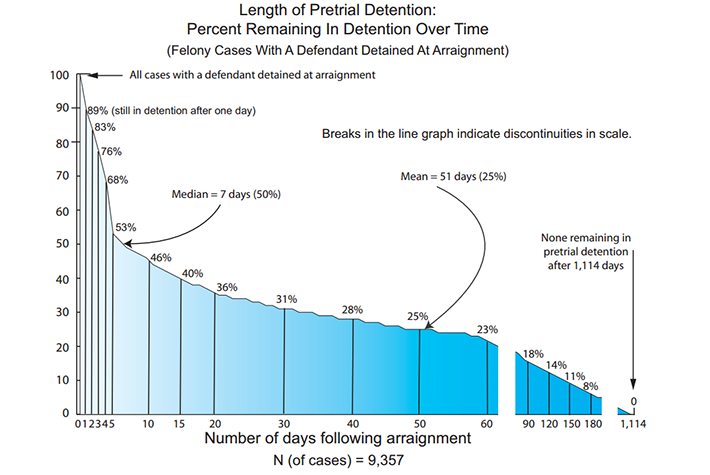

Length of time that defendants spend in jail before trial (source). Although 50% are out by day 7, 25% are still in by day 50, 10% are still in by day 150, and one was still in after three years

I talked to a correctional psychiatrist a few weeks ago who was telling me that conditions for inmates awaiting trial were worse than conditions for already-convicted inmates. The convicted inmates get officially integrated into whatever prison they’re in and receive various jobs and privileges. The inmates awaiting trial just sit in their cells doing nothing.

People who commit serious crimes might be looking at years or decades in prison. Do the few months they gain or lose because of bail really make that big a difference?

Yes. First, because most people aren’t looking at decades in prison. This article tells the story of a man accused of attacking some police officers; he claimed innocence and expected to be vindicated at trial. Prosecutors offered him a plea bargain of sixty days in jail, which he refused. But he ended up spending more than sixty days in jail waiting for trial, which kind of defeated the point.

Second, because much of the time this ends in people just taking the plea bargain. For example, the man in the article above almost took the plea bargain after serving sixty days in jail – an understandable choice, since it let him walk free immediately with time served. But this would put a guilty plea on his record, which would make it harder for him to get jobs in the future and reframe any further crimes he might commit as “repeat offenses”. If his case goes to trial, he might have been be found not guilty and avoid the black mark.

Third, because people who are detained pretrial end up getting longer sentences. Some of this seems to be because they’re less able to contact their lawyer and prepare a good defense. Some more seems to be related to prosecutors setting harsher plea bargains for imprisoned defendants because they have a worse bargaining position. And some more might be related to psychological factors where judges think of people who just showed up from jail as “more criminal” than someone who came to the court from their home.

This legal advice site advises suspects not to stay in jail before trial even if they don’t mind the environment and just want to get it over with. It confirms my friend’s suspicion that jails are worse for people awaiting trial than for convicted offenders, but also notes some other interesting aspects. People in jail have a bad habit of making incriminating statements that get reported and used against them on trial. Suspects out on bail can rack up prosocial accomplishments to list off at their trial – they give the example of going to a counselor and making restitution to victims. And they get the option to delay their case until the trail grows cold and prosecutors get bored and everyone just agrees to a lesser sentence.

(something I didn’t realize which is relevant here: 96% of felony convictions involve guilty pleas. Plea bargaining is the rule, not the exception, and anything which makes it easier or harder is going to impact the large majority of cases)

There have been a bunch of studies trying to determine to what degree bail vs. pretrial detention affects case outcome. Some early studies like this found that it could alter sentence length by about ten percent, but the data were necessarily not very good – there’s no way to randomize suspects, and the sort of hardened criminals who don’t get bail are the same sort of hardened criminals who maybe deserve tougher sentences. People tried their best to control for all observable factors, but this never works. Better is Gupta, Hansman & Frenchman, which tries a quasi-experimental design based on suspects’ random assignment to more or less strict judges who are more or less likely to demand lots of money for bail. Suspects who are assessed bail are 6% more likely to be convicted (they’re also 4% more likely to reoffend, which is weird but might be related to imprisonment hardening criminals and increasing recidivism). Stevenson tries a similar method and finds that inability to make bail produces a 13% increase in convictions, mostly through more guilty pleas.

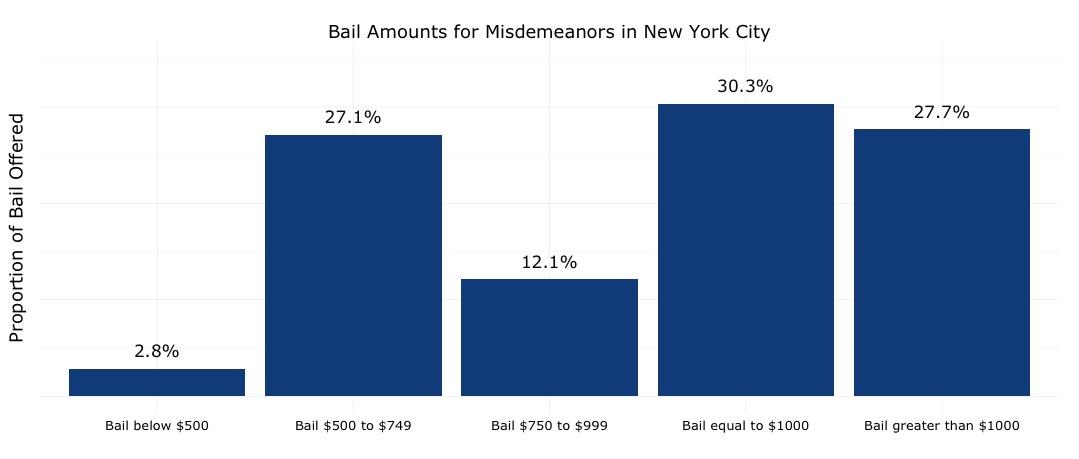

This study also finds that size of bail was less important than whether there was bail at all, which confused me until they pointed out that most suspects are really, really poor. As per the Stevenson paper:

Some of these defendants are facing very serious charges, and accordingly, have very high bail. But many have bail set at amounts that would be affordable for the middle or upper-middle class but are simply beyond the reach of the poor. In Philadelphia, the site of this study, more than half of pretrial detainees would be able to secure their release by paying a deposit of $1000 or less, most of which would be reimbursed if they appear at all court dates. Many defendants remain incarcerated even at extremely low amounts of bail, where the deposit necessary to secure release is only $50 or $100.

The New York Times notes that

Even when bail is set comparatively low – at $500 or less, as it is in one-third of nonfelony cases = only 15% of defendants are able to come up with the money to avoid jail.

And from here:

The guy in the NPR article above – the one who might or might not have attacked some cops – was in jail for 60 days because he couldn’t make bail of $1000.

So bail causes people to be stuck in jail for months, increases guilty pleas independent of defendants’ actual guilt, and causes more convictions and longer sentences. Since many of the people harmed by this are innocent, or deserve less punishment than they end up receiving, this seems like an important point of leverage at which to try to fight incarceration. On the other hand, bail is supposed to serve a useful purpose in preventing suspects from running away. It is possible to do without?

Maybe. Washington DC is one of the highest-crime areas of the country, but it uses an alternative system without monetary bail which uses an algorithm to calculate risk, releases low-risk people, and keeps high-risk people imprisoned without bail. It looks like about 10% of Washingtonians, versus 47% of other Americans, are detained in jail pre-trial. Of Washingtonians released without bail, 87% show up for all court dates, and 98% avoid committing violent crimes while free.

I’m not able to find a good comparison between Washington and other jurisdictions, but this page on bounty hunters gives the unsourced statistic that 20% of people on bail fail to show up for court anyway. This equally-credible-looking site gives an equally unsourced statistic of 10%, and notes that these people are more likely to be flakes who forgot their court date than supercriminals who have donned a fake mustache and are on their way to the Cayman Islands. These numbers suggests that Washington’s no-show rate is about the same as everywhere else’s.

Bronx Freedom Fund is a charity that helps people pay bail. They claim that 96% of the people whose bail they pay show up to trial, which matches the numbers from Washington and the numbers from normal places where people have to pay their own bail. I am sure they select their beneficiaries very carefully, but if it’s possible to select a group of people who are definitely going to show up to their trial whether they can make bail or not, why are those people still in jail?

I can’t find any studies clearly proving this, but it looks like there’s no obvious and proven tendency for bail to improve show-up-at-trial rates, and some evidence that with good risk assessment and selection 90% of people released without bail will show up to trial, which may be around the same as the rate for people who do get bail. This would make all of the problems with bail not only outrageous but pointless, not even the unfortunate side effects of a generally-reasonable policy.

It looks like there are two possible solutions – one small and short-term, the other systemic and long-term.

In the short term, there are some great charities – like the aforementioned Bronx Freedom Fund – that pay people’s bail. If the people show up to trial (which, again, 90% or so do), then the charity gets its money back and can use it to pay more people’s bail, ad infinitum. This makes them very high-value per dollar.

I’m not sure how much to trust BFF’s self-reported statistics. I see that on their front page they mention that “defendants who await trial in jail are 4x more likely to be sentenced to time in prison”, which is much more than any of the studies above report and which is probably a misleading uncorrected raw estimate. I see they say that “$39 can help us secure someone’s freedom”, which since average bail is something like $500 and only 2.8% of bails are less than $50 might be more of a “this is the lowest bail that has ever occurred in history” than any kind of representative estimate. But I don’t really hold it against them to give technically correct but misleading numbers in an advertising pitch. The question is – what are the real numbers? GiveWell and Open Philanthropy Project have been looking at them, but I can’t find a complete writeup, so let me do a terrible and very approximate job of trying to estimate them myself.

They note that their average bail is $790. Supposing that their 96% success rate is true, the average case costs them $30 – they cite a similar figure in their own literature. If, as they say, the average pretrial detention period is 15 days (which more or less matches the chart above), they can keep someone out of jail for $2/day even without selecting the worst cases.

They also note that their clients get cleared of all charges about half the time, compared to only 10% of the time for people in jail. I don’t know how much of this is selection effects, but suppose we take it at face value. And suppose that an average prison sentence for whatever kinds of petty crimes these people commit is two months. That means they’re saving the average suspect about 25 days worth of prison sentence, and improves their cost-effectiveness. I’d say this comes out to about $0.75 per jail day prevented, but that might be double-counting some people who, had they been in jail, would have had the time deducted from their sentence. Let’s say somewhere between $0.75 and $2.

A confusion: their 2014 annual report notes that they received $53,000 in donations and helped 140 people, suggesting a cost of $380 (not $30) per person helped. In 2015 they helped 160 people with $120,000, suggesting a cost of $750 per person that doesn’t seem to improve with scale. A similar organization, Brooklyn Community Bail Fund, got $404,800 from Good Ventures, and boasts of helping 1,100 people, for $367/person (this is a very rough estimate; it assumes this is all in the same year and they got no other donations).

I’m not sure why these numbers are so much bigger than the ones derived from first principles, but taken seriously, if we continue to assume that each successful case saves an average of forty days in jail, they prevent a jail day for about $10.

We compare to other efficient charities. GiveWell thinks it takes antimalaria charities about $7500 to save a human life. If that person lives another 20 years, that’s about $1/day.

So using their own numbers, these bail-related charities might be able to prevent imprisonment at the same cost-per-day as other charities can save lives. Using less optimistic numbers, they might be able to prevent imprisonment at about ten times the rate. Depending on where you fall on the death vs suffering philosophical tradeoff, this might be attractive. I’m confused these charities haven’t received more attention, if only to debunk them properly.

And even though everyone likes to talk about how individual charity doesn’t work and only systemic change can make a real difference, paying the bail of 50% of the people in the United States currently awaiting trial would be well within the abilities of one philanthropic-feeling billionaire, after which the money could be recycled again and again for the same purpose. I agree this is a kind of hokey calculation since it doesn’t include the overhead cost of getting the money to the suspects, but it’s still shocking how small the amounts involved are compared to other social problems.

In the long-term, we probably need some kind of criminal justice reform. The Obama administration seemed to be pursuing some kind of fourteenth amendment argument to get a court ruling that monetary bail was illegal. Some libertarian groups like Reason and the Cato Institute are on board. Some charities, like Equal Justice Under Law, are supporting the same cause.

I don’t think that bail reform is the largest or most important change that could be made to the US criminal justice system. But I think it might be tied with drug reform for the easiest. And given how well politics has been going lately, this might be a good time for lowered ambitions.

The most impactful criminal justice reform is arguably better care for young children.

There is a program that results in:

– 59% reduction in arrests among children

– 72% fewer convictions of mothers

– 48% reduction in child abuse and neglect

– 56% reduction in emergency room visits for accidents and poisonings

– 67% reduction in behavioral and intellectual problems among children

– $41,000 savings in government spending per child served (the program costs about ~$6,000) resulting in a 570% return on investment

What is the program? Nurse Family Partnership

How does it work? A first-time pregnant mothers is paired with a free personal nurse from their first trimester until the child is two years old

How has it been assessed? By three randomized controlled trials with up to 18,000 participants (not a bad n). See here

As far as I am aware this is one of the most effective social interventions for the United States. Happy to be shown others that have equally impressive results and have undergone similarly rigorous analysis.

I’ve seen BFF (Bronx Freedom Fund) present a couple of times, and have visited a bronx arraignment court. Disclaimer: I have supported them financially, and expect to in the future. I have not independently verified their numbers, but I can shed some light on the approach I understand them to be taking. Any errors are mine.

(I encourage you to email me if you want an intro to the Executive Director who could answer a lot more of this a lot better than I can. I’ve also passed this on to him and encouraged him to post or reach out.)

1. $39, or whatever in that ballpark, to keep someone out of jail, is the average forfeited amount for bailing someone out, i.e. if they pay $1000 in bail and 3.9% of the time it is forfeited, the average cost would be $39. This does not include foregone interest for 6-ish months, or the overhead of paying and retrieving the bail.

2. The $300-400 numbers for money raised / people served, is mostly the cost of running around to courts with a bag full of certified checks and paying bail. The obstacles to doing this efficiently (for them, or just a friend/family member) are egregious. There are other activities as well, they can describe them better than I can.

3. The change in outcome numbers (I’m assuming they’re all above board) are too significant, and too large a portion of the total population, to be explained by cherry picking. If before BFF 90% were convicted, and they bail out 20% of whom 10% are convicted, the situation surely changed. They have gained some scale and are now bailing out enough that either their numbers will drop precipitously, or the change in outcome will be undeniable.

4. Even a few days in jail awaiting trial can lead to job loss. Obviously a conviction is a serious issue. The positive effects of avoiding pre-trial detention and resolving the matter without a criminal conviction go far beyond the 15 or however many days out of jail.

[By the way “show up for all your appearances” if it gets pursued is a number like 15 or 20 over several months. ]

5. There are other benefits, such as reducing the substantial costs to the city (supposedly averaging $670/night — there may be material quibbles with that number, but there’s surely some significant marginal cost to the city).

6. The real goal here is not only to pay one bail at a time, but to gather data and experience that helps reform the system. This can happen in small ways, such as concentrated lobbying for something as basic as an ATM in the building (seriously, the hurdles to making payment are awful), or larger ways such as providing evidence (e.g. to a recent decision in Houston), or technical assistance to other bail funds. BFF should hopefully put itself out of business in the Bronx, which would “capitalize” a ton of benefit without ongoing operating cost.

The larger the claimed effect, the more I believe it is due to cherry-picking.

What do you mean by “too large a portion of the total population”? BFF bails out very few people, so it is very easy for them to pick the cherries.

Scott mentioned quasi-experiments showing 5-15% reduction in conviction rates from bail.

They are now bailing out a meaningful fraction of those eligible (NY law limits charitable bail to $2000). There is a lot of randomness that winnowed the population also based on where they got referrals from and just the logistics of having one full time person.

There’s some fraction and some result beyond which cherry picking cannot mathematically do all the work. They probably were not there in 2015 (when the evidence is merely compelling), but I believe they will be this year.

I don’t think the national results are representative of what to expect from this population.

It’s worth mentioning that New Jersey recently eliminated cash bail, and other states like Pennsylvania seem to be moving in that direction.

And yeah, I agree that this is low-hanging fruit. Along with bail and the drug war, we also should move towards reducing overly long prison sentences for nonviolent property crime, and putting more resources into rehabilitating people and reducing recidivism. Our whole probation system is kind of a mess too, there are way to many stupid traps built into it that end up in people on probation going back to prison over really minor or pointless issues.

Poor people have a smaller stake in society. They have less to lose (fortune, social position, career, rank) and may thus be less likely to care about the consequences of their actions — more likely to be violent, to brawl, to commit petty thefts, to commit vandalism, to use drugs, etc..

For well-off people, the incentive for proper behavior is provided by the threat of firing, social ostracism, public opprobrium, bankruptcy, divorce, etc.. This need not work for lower-class people.

Thus, they may need a different sort of incentive for proper behavior. This is currently provided by the certain knowledge that they won’t get a free pass from the justice system for such deeds, as they lack the money to make it work for them.

Bail reform will almost certainly lead to substantially more petty crime, since poor people will have much less to be afraid of.

I’m surprised by how isolated this whole discussion is from any shred of historical context. Has the U.S. been this kind of outlier in incarceration rates for ten years? Fifty? A hundred? I’m not asking rhetorically; I really don’t know. But it seems germane, if only because it might make it easier to associate it with whatever cofactors might help explain it.

I did allude to there being an apparent move away from institutionalization for criminals with mental problems earlier, but again, the history of that is not something I follow. (I was half hoping someone else with more familiarity would expand on or refute it.)

Scott covered that here: https://slatestarcodex.com/2016/03/07/reverse-voxsplaining-prison-and-mental-illness/

Thanks. That’s pretty comprehensive, and I’d forgotten he’d posted that. I’m not 100% sure I’m convinced, but I’m sure not convinced of the opposite, either.

My experience: https://jasonboisvert.blogspot.com/2016/03/adventures-in-incarceration-2.html

How is the bail amount calculated?

Also, how much does it cost to jail someone for a day? I guess that 60 days of incarceration will cost a lot more than 50 or so dollars anyway, so that seems to be a net loss even if we disregard the accused and are only concerned with the taxpayer’s money. And of course, as long as they actually go to court, it seems that they get reimbursed for most of the cost anyway.

Btw, are the people who did not pay bail and who were then freed of all charges reimbursed for the time they had to spend in prison? I guess they aren’t but they should be.

Ha ha, no. We’re lucky they don’t require them to pay for the room and board. Oh, wait…

(Useful context: their Form 990s, on guidestar)

1) You would expect for substantial amounts of money to not be spent each year, since bail gets returned. That is to say, to some extent the limiting factor is likely not the amount of money, but rather the amount of time the money spends locked up + their ability to find and evaluate people to pay bail for.

2) Not sure where the second figure came from (I mean, I see it in the link, it just doesn’t match up with their tax returns); their 2015 form 990 lists $46,832 as their total revenue. Possibly a big late donation received after the tax year ended that they wanted to boast about or something?

(The 2014 letter and Form 990 match up.)

3) Here’s a summary of the Bronx Freedom Fund’s 2015 spending & assets:

$23,391 – “Professional fees and other payments to independent contractors” (presumably paying people to evaluate potential candidates, supporting other organizations in setting up similar funds, and general administrative spending)

$5,940 – Other spending, including as $603 on “bail bond expense” and $3,368 on “insurance”

They ended the year with $192,793 in assets, of which $65,460 was money used to pay for bail (which they expected to get back, and which was therefore an asset) and $128,533 was cash. Between 2010 and 2015 they received $214,989 in total donations, and gained $40,723 in assets.

$603 + $3,368 = 3,971; 160 people helped in 2015 suggests a bail-only price of ~25 dollars per person, very close to Scott’s guestimate of ~30/case.

By the way, here’s a criminal justice reform that I’ve never heard anybody suggest: take the juries out of the courtroom. Lawyers and judges are very busy people, so they only carry on trials about 4 or 5 hours per day, and a lot of that is inadmissible to the jury.

So, videotape the trial without the jury present, delete all the parts that were ruled inadmissible, and then call the jury in and show the videotape to them in 8 hour a day stretches. The one jury I served on took two entire work weeks, but if we did it my way, it would have only taken us 13 or 14 people (with alternates) one week. That’s a savings of 13 or 14 individual-weeks.

Btw how much are you reimbursed for being drafted to jury duty? 2 weeks is a lot of lost time. And how high a fine do you have to pay if you don’t want to do it?

Looking it up, here in Portland, Oregon it’s:

$10 (9.00€) per day for the first two days;

$25 (22.50€) per day thereafter.

What? Isn’t that less than they’d pay you per hour at McDonald’s (on the first two days)? That’s ridiculous. Conscripts in in Switzerland are reimbursed 80% of their salary for the time when they have to do the training and it is supposedly considered good manners (i.e. most companies do it) that their employer (unless they’re self-employed obviously) cover the remaining 20%.

I don’t know what McDonald’s is paying right now, but it wouldn’t surprise me if that’s the case. The current federal minimum wage is $7.25/hr, and in Oregon it’s $9.75/hr. So if McDonald’s is paying nearly anything above minimum wage, it is probably paying more per hour than the county is paying per day for jury service. (They do pay for the transit ticket and mileage to get to the courthouse, but the transit is only $5.00/day for TriMet.)

The best part is, according to that website, if your employer pays you wages for the day despite jury service, you don’t get the $10.

Full-time employers in the States usually cover some jury time, but often not enough for a long trial without dipping into vacation time.

It seems fairer to me for the government to pay up, and that seems to have been the original intent. But the pay for jury duty was set at a time when eight bucks a day was a fair salary, and has not been indexed to inflation.

Why isn’t jury duty considered labor and therefore paid the minimum wage?

If you make it to actual jury selection and you really want to get out of it, just tell the lawyers that you hate cops (and make up a semi-plausible reason for it in case they follow through). They’ll drop you like a rock.

I just don’t register to vote. Much easier.

A lot of courts are now pulling from drivers’ license lists and other places, too.

They already did that 40 years ago. One of my parents got called up for jury duty due to having an American driver’s license, despite not being American.

I like this idea in principle, but it raises all kinds of questions about who watches the cameramen and the video editors. I can imagine all kinds of subtle ways to bias the presentation even if all the video is legit and unaltered. Editing is not completely mechanical either — what happens if somebody says something that refers to something that happened in the removed spans, which makes perfect sense to people who were there for the whole thing but is confusing or misleading to those seeing the edited version? Is the editor sharp enough to snip that out, too, and can that even be done without making the surrounding context incoherent?

Of course, it might be that in practice these considerations more than outweighed by removing the effect on the jury of actually hearing things they are directed to disregard; I’ve never understood how that would actually be possible. But I’ve never been on a jury.

Then you have to add the problem of how easy it is to make entirely fake video footage. How this would play out I don’t know. Would bad police departments start to do this, increasing bad convictions? Would juries be less likely to trust video, increasing bad acquittals?

I do sort of like the idea that a hung jury means you could just play the video for another twelve jurors, rather than having a whole new trial.

All those issues could be resolved satisfactorily, though. We now have court recorders making a transcript of the trial, and complicated rules for what evidence may be presented to the jury. It’s not like we couldn’t figure out how to deal with video footage. (Fake video is a problem, but it’s the same problem as fake evidence generally being accepted.)

It seems like this would have several big advantages:

a. Making jury duty less of a disruption in your life would probably make it easier to get people for jury duty–there would be less incentive for busy people to try to opt out. I don’t know how important this effect is, or how we’d find out.

b. Being able to rewind and replay stuff seems like it would work well for resolving questions about what happened. If you provided this plus a transcript, you’d have two different ways of getting the same information, which would probably lead to jurors doing a better job understanding what happened.

c. You could imagine having a process for rerunning a trial by simply choosing a new jury and showing them the footage–this would cost enormously less time and money than rerunning a normal trial. That leads to lots of nice things like:

(1) When there’s an appeal and some piece of evidence is thrown out or something, you might often be able to simply black out that part of the testimony with a notice that this evidence was excluded on appeal, but not have to rerun the whole trial.

(2) You could automatically rerun the trial with a new jury in death penalty cases, or when there’s a mistrial.

(3) You could even do some statistical rerunning of trials with new juries to see what fraction of the time you got the same answer, which would be nice for quality control.

d. Changing the venue of the trial would be enormously less expensive–you could do the trial locally, and then if you needed to do so, you could find a jury somewhere far away. And again, if an appeals court decided there was a problem with your jury, there’d be an easy fix.

e. It would make trials actually accessible to the public–instead of having to go to the courthouse on a given day, you could view video of a trial when you wanted to. You could also randomly sample trial footage to see how judges, prosecutors, etc., were doing their jobs.

I don’t know enough to know what the downsides would be.

Wow, those are much better reasons for my idea than the ones I came up with!

Another possible reform would be to speed up pre-trial dawdling.

Caveats: I’m in California. Which is not the Bronx. I am a criminal prosecutor, but I do not know New York law. Sometimes state laws are predictable; bail laws and practices vary widely and I may be making inferences that are invalid. I base none of this on any special knowledge I have about Bronx Freedom Fighters.

First off, BFF’s claims don’t seem credible to me.

BFF claims that 55% of clients get a dismissal of all charges, and another almost-40% get something similar to a traffic ticket. That leaves 5% of the people who make bail on a misdemeanor getting misdemeanors, while 92% of the people who remain in jail settle their cases, of which the majority (at least 46%) end up with a criminal record, which I’ll assume is a misdemeanor. (“Likely,” a criminal record.) BFF has the bail fund for only misdemeanors.

Let me just say that if that’s true, it’s appalling – a misdemeanor conviction rate at least *nine times* higher for people in than out. I don’t believe it. I think BFF is lying to us, and I base that solely on the claims they make. I’d love to see the raw data.

There are ways to get partway there just by minor lies: If you’re making bail for people who have been arrested but not charged with crimes, some percentage of them will not be prosecuted. If you then compare that to people already charged, you can move the needle. Still, that’s a big number.

Alternatively, they’re only making bail for a small subset of misdemeanors, misdemeanors that are likely to resolve informally.

Further alternatively, “dismissal of all charges,” could be referring to some process of expungement or dismissal after a guilty plea. If this is part of it, that’s dishonest.

BFF’s claim that they have a 96% record of “attending all their court dates,” seems unlikely to me, too. This gets complicated and I DO NOT KNOW NEW YORK LAW and I am too lazy to look it up, but usually attorneys are allowed to appear for their clients in pretrials on misdemeanor cases, so while the defendants don’t fail to appear, neither do they “attend all their court dates.”

Here’s what happens in my area of California:

You commit a misdemeanor. Most of the time, you’ll sign a promise to appear. If you have past warrants or you’re real drunk or you decide the best course of action is to run from the cops, you get hooked. Bail gets set at schedule. If you don’t have money, you don’t bail out. The percentage of in-custody misdemeanants in my jurisdiction is very low. Some fraction are held a few days until arraignment, but almost all of them are released at that point.

If you are arrested for a felony, you’re far more likely to get hooked and stay in.

The other item here is those discussions of people held for a very long time without trial are not exercising their speedy trial rights. In California, you have a right to a misdemeanor trial if in custody within 30 days, and a right to a felony trial in about 75 days. (Felonies have two separate steps, totalling about 75 days.) The reasons people stay in for a long time – sometimes a very long time – is often that their defense attorney is hoping the prosecution loses witnesses/gets tired/loses focus/whatever.

Also, in California, most inmates serve their time in local jails. You can’t go to prison without doing something very nasty; if you’re a recidivist methamphetamine manufacturer, you can’t go to state prison without a violent or serious prior conviction, or if you’re a prior sex offender. (Fun fact: Simple possession of meth in California with a prior for armed voluntary manslaughter is a misdemeanor. If you have a prior for indecent exposure though, you can go to state prison. Logic!)

Bail in some states is less regulated than in others. In some states, the bonds company can charge what they want. If there’s a $50K bail, and you’re a good risk to show up, the bail bond company charges you based on risk and profit. In California, the rates are statutory (10%, but you can do it on credit sometimes.)

Those who make higher bails tend to be lower risks to run. When they do run, they get caught more. Bail bond companies do not losing $100K. (The company forfeits the bond in California if the defendant doesn’t show up and isn’t delivered back within a year; that’s an oversimplification, but it’ll do. The bail companies will find you and be unpleasant about it when the money’s big.)

I’d love to see the Bronx numbers on what percentage of misdemeanants are granted OR release by the courts vs. the number held on bail. Anyone have that data?

I am imagining some stuff here, but I expect that one thing that BFF would do is send out volunteers to knock on doors on make sure people show up instead of flake out, since BFF’s money is on the line.

According to Pew Research Center about 35 and 46% of respectively property and violent crimes are reported to the police. The fraction of the reported crimes that is cleared by the police is respectively below 20 and 46 per cent.

Taking 1:4 ratio of violent to property crimes in Washington DC, we can make a first order estimate of the actual crime rate. If 2% were arrested for violent crimes then about 10% actually committed a violent crime and about 50% committed either violent or property crime while free.

You seem to by making the assumptions that those are the only classes of crimes.

Anyone arrested for a few grams of [insert substance here] wouldn’t be in those numbers and those are neither violent nor property crimes so wouldn’t show up in the Pew numbers.

You’re also making a lot of other strange assumptions, such as assuming that crimes are evenly distributed and that people who’re on bail are representative of the set of all people who commit crimes.

For example if there was some subset of people who are both responsible for a disproportionate fraction of unsolved crimes and are also less likely to get caught (lets call them “the most competent criminals”) then that destroys your estimate since they’re less likely to be part of the set of people on bail.

The lack of people looking at non-US bail systems is kind of screwy. Other countries have functioning bail systems, few are as fucked up as the US one.

Take the UK system for example.

“You can be released on bail at the police station after you’ve been charged. This means you will be able to go home until your court hearing.

If you are given bail, you might have to agree to conditions like:

living at a particular address

not contacting certain people

giving your passport to the police so you can’t leave the UK

reporting to a police station at agreed times, eg once a week

If you don’t stick to these conditions you can be arrested again and be taken to prison to wait for your court hearing.

You’re unlikely to be given bail if:

you are charged with a serious offence, eg armed robbery

you’ve been convicted of a serious crime in the past

you’ve been given bail in the past and not stuck to the terms

the police think you may not turn up for your hearing

the police think you might commit a crime while you’re on bail”

The surety system also doesn’t require people to have cash up front. A person stands as a surety, and pledges that they will pay x amount of money if the person doesn’t turn up to court. This is only put in place if the police think the person is a flight risk etc. and that the surety system will make them turn up. This means that it doesn’t just fuck over people who don’t have cash savings, and you only have to pay if you actually disobey.

I mean, seriously, sticking people in prison because they can’t pay is fucked up. And there are other systems which seem pretty functional. Justifying things before you fuck up people’s lives is important.

Putting a genuinely innocent person in prison for weeks/months only to clear them of all charges seems like a great way to produce criminals. I mean, imagine: you’re an employed, law abiding citizen who’s been falsely accused of something. You get arrested with no warning, and while you sit in prison your children are taken into foster care (because you’re a single parent and you can’t look after them from prison), you loose your job, and your home. You get out, and you’re quite rightfully pissed off at the justice system, homeless and unemployed, and are going to have to fight to get your kids back (lawyers fees). And the guy you’ve been sharing a cell with for the last two months has been telling you about how easy it is to make money breaking into houses.

Innocence until proven guilty is a really, really important part of the justice system. Actually judging how much of a flight risk someone is before you demand money should be fucking standard.

Instead, it fucks over people who don’t have close friends or family. Not sure that’s an improvement.

Seems like a marginal improvement to me – trustworthy individuals who would be a net positive to society are more likely, all else equal, to have friends willing to stand up to them.

It’s nowhere near ideal… but I’m thinking it might still be better than the current system.

Trustworthy individuals who would be a net positive to society are more likely, all else equal, to engage in commercial trade of the sort which results in monetary income. And money is fungible, whereas family ties are vulnerable to random chance.

Family ties are not all that random. Trustworthy individuals are likely to be related to other trustworthy individuals, because of genetics.

Everybody starts with a family. Almost everybody, even untrustworthy criminal types, in some contexts especially untrustworthy criminal types, starts with a family willing to bail them out of jail or whatever. Whether your parents e.g. get hit by a truck when you are twelve, is mostly down to luck.

@John Schilling: Unless your name is Bruce Wayne. Although, then you should have enough money for a bailout anyway 🙂

One easy-to-reach improvement would be to try to shorten the time between arrest and trial. That requires more resources, but probably not enormously more resources. Suppose we change things so that instead of spending 45 days in jail before going to trial (where not being able to make bail or convince a bail bondsman you’re a good risk= staying in jail), you stay a week in jail before going to trial. Then not being able to make bail is much less of a big deal.

More resources going to processing cases, fewer resources going to maintaining jails. Might end up costing more or less overall.

Surety isn’t always used, the whole point is that there are multiple systems. So if someone says ” I haven’t got anyone who would trust me to turn up at court”

Surety isn’t always used, and it doesn’t have to be. The whole point is that there are other systems.

So when untrustworthy jim says “nope, no one trusts me to turn up to court”, they can use other systems, like tagging.

And the court has processes for talking to the surety about repayment if the person doesn’t turn up. So that they aren’t just fucked over and ending up in debt. Kind of like fine repayment?

In most cases, you don’t have to put a financial penalty in place to make people turn up. Not turning up to court looks bad, has consequences, etc.

People who aren’t trusted not being able to get bail is still a way, way better system than poor people not being able to get bail. hitting the people likely to actually be a problem, rather than the people least likely to be able to cope, is a better option.

Freedom from arbitrary detention is really, really important.

Scott (and everyone else interested in plea bargaining).

IMHO, the first place to start is this 1978 article by John Langbein, Torture and Plea Bargaining.

Langbein argues that the medieval system of tortured confessions was driven in large part by the laws of evidence, which only allowed confession on the testimony of two unimpeachable witnesses, or on confession of the accused. The necessity of keeping public order quickly led to a formalized structure where the authorities basically tortured confessions as necessary. Unfortunately (1) torture is bad in an of itself and (2) because torture tests the ability to endure pain instead of the quality of the evidence, it subverted the justice system as a tool to dispense justice.

Langbein argues that plea bargains are similar in many ways – we have a system of due process broad enough that it’s not practicable that everyone accused of a crime actually get a full trial, and as a result, a practice has evolved where the cost for holding a trial is doubling your sentence if you lose, and if you’re poor, it’s also sitting in jail until you go to trial. Like torture, this to some degree tests the defendants’ resolve rather than their innocence.

http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/fss_papers/543/

America is commonly singled out (among developed western nations) for A) having high inequality (which might be a dubious claim, but taking it as given) and B) having high rates of incarceration. I’m surprised that no one has put two-and-two together and looked at the impact of our abnormally high rates of incarceration on inequality (or maybe someone has and I haven’t found it yet). It stands to reason that the more we saddle the poor with jail time, fines, and damaged records, the more difficult it will be for them to get ahead. Just a thought.

There’s also the reverse story: high wealth inequality causes poor people to conclude that they are excluded from the benefits of the legal market economy and to therefore adopt alternative strategies regarding employment.

Yeah, that seems totally plausible too. But part of that story would have to be unusually high crime rates — and those high crime rates would have to be caused by inequality, and not, say, stricter drug laws.

That’s mostly the conclusion of evolutionary psychologist Martin Daly’s new book Killing the Competition. Although the violence is not just an alternative employment strategy, but an alternative status-gaining strategy. Women are still peeling men off the top of the hierarchy, and when nobody in your local hierarchy has access to the wealth-gaining system to show status, violence against people who disrespect you gets you status and therefore access to women.

It is a weak argument (as you present it, obviously very briefly) as if violence against men is status seeking for the purpose of mate selection then you have an issue. Either violence against women should be anti correlated with the above violence against men, or women must not use violence against them as part of their mate selection.

That one, unfortunately, for a large class of women.

https://slatestarcodex.com/2014/08/31/radicalizing-the-romanceless/

@The Nybbler

My reply should have had an additional line, that if women are not using violence against them what is the Evopsych reason for it.

How long would it takes for judges to compensate for the philkrimaic-feeling billionaire by increasing the bails?

I don’t believe that any country of which that statistic is true has an honest justice system.

Why?

Because we should arrest more people who didn’t do anything wrong.

/s

@vV_Vv

People make mistakes. The prosecutor is human and the evidence was collected by human police officers, so you’d expect him or her to offer unfair plea deals in a decent number of cases, because somewhere in the justice system, a mistake was made. A dishonest justice system provides strong incentives to accept an unfair plea deal.

A 4% error rate for plea deals would be amazingly low.

A dishonest justice system can also send you to trial and convict you even if you are innocent. Why would a plea deal be any better?

That is a weird objection.

The argument is not that a smaller number of plea deals is evidence for a honest justice system, but that a large number is evidence for a dishonest justice system.

You seem to be arguing against a claim that was not made.

I think I’d be a little happier with Washington’s scheme if the city didn’t have such a high crime rate. As well, it’s kind of pointed how you don’t say anything about non-violent crimes being committed by people on bail.

To me it feels like that most of the solutions and discussion here seem to have a fundamental assumption that most people who are arrested are not guilty, and are being railroaded by the cops and the justice system. It would be interesting to see a discussion which started from the opposite assumption: “Given that most people arrested are guilty, how can we we make the system more humane and efficient?”

There’s a lot of fundamental questions in the underlying statistics at work here. I don’t know if I’m just being subconsciously overly defensive as a member of the political right being (rightly or wrongly) blamed for the problem, but at a conscious level I want to know the truth of the problem so I can accurately model it, so, please, correct me if I’m wrong, missed something or misrepresented something.

There are a lot of possible partial explanations for why the US incarceration rate is so high, which all depend on a number of other statistics that I can’t find a clear answer for. As a temporary source, I’m using the UN’s International Statistics on Crime and Justice (https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/Crime-statistics/International_Statistics_on_Crime_and_Justice.pdf) which appears to be from 2009-2010, but I don’t think US incarceration rates changed that much, so the analysis should still be valid. However, the document is more analysis than statistics.

First, to get this out of the way, are incarceration statistics comparing apples to apples? The statistics Scott cites are fairly comprehensive, but there are some things I didn’t get from a quick reading. For example, do other countries include ‘Immigration Detention’ and ‘Civil Commitment’ in their criminal incarceration statistics? Anyone trying to discuss this should read Chapter 8 of the UN study, “Crime and criminal justice statistics challenges“, for a discussion on how hard it is to find comparable valid statistics, which is why I’m incredibly hesitant to make policy prescriptions based on those statistics.

One of the things that stood out in the study was the Suspect Rate. “The total number of persons brought into contact with the police or otherwise contacted by the criminal justice system – persons suspected, arrested or cautioned – were defined in a similar manner as the number of recorded crimes, excluding minor traffic offenses and other petty offenses. The number of suspects is in most countries smaller than the number of recorded crimes, because many crimes are not cleared, i.e. a suspect for the offense has not been found.” The study cites the US as being a country with a high suspect rate, but other countries listed as being high, such as Finland, New Zealand, and South Korea don’t have a high prison population per capita. If they were also somewhat high, I could see the US having a high prison population in part because our justice system solves (or, admittedly, ‘solves’) a higher percentage of crimes than other countries do. The fact that we have so many drug crimes might also factor into this, as these are crimes (or ‘crimes’) which only come to light when a suspect encounters the police.

What’s the argument in favor of the current bail system? I feel like I’m missing that.

It just seems obviously wrong to me that the freedom of someone accused but not convicted of a crime should depend on their ability and willingness to put up money, and I’m not sure what sort of coherent arguments exist for such a policy. Certainly if we didn’t already have the current system in place, I can’t think of an argument for adopting it that wouldn’t be laughed out of the room. But since I don’t understand why it exists in the first place, it’s possible that I’m missing something important.

To illustrate the issue here: a lot of the pro-bond arguments I see in this thread are actually just arguments for not releasing people accused of serious crimes. They’re not arguments for why their release should be contingent on ability/willingness to post bond.

The best steelman I’ve seen is in the Priceonomics article I linked two posts up.

Basically:

– Actual bail does increase the frequency at which released defendants show up for trial. (Not really surprisingly). I don’t know if you surrender your bail if you commit more crimes, but if so, I would guess it also decreases the pre-trial crime rate.

– Bail bonds essentially function as insurance against the possibility of running – you are making a deposit with the person who is going to chase you down, the pool of which covers the costs of chasing down people who don’t show up for trial.

Perhaps it’s a bit of a relic from an earlier time where if you could flee the state or country, you really were safe from prosecution. Maybe bail makes less sense in the modern world where it is harder to cross borders, and easier for the law to pursue you across states/countries.

If 20% of people in jail/prison are awaiting trial, and they’re waiting for an average of 51 days, doesn’t that suggest that the average sentence should be on the order of 250 days? Is that plausible?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Criminal_sentencing_in_the_United_States says the average is 55 months given a guilty plea, which is almost all convictions. That’s 6.5 times too high. If 13/15 people get either not-guilty or no prison/jail sentence, the numbers seem to work out. Is that plausible?

Eh, maybe. I couldn’t immediately find something for that.

Various things might confuse the issue. 55 months is probably dated. And I guess people who aren’t going to get prison/jail sentences are probably less likely to be incarcerated while they wait, I’m not immediately sure whether that’s a thing to take into account.

I’m not following the logic stating that because the average pretrial detention is 51 days, that the average sentence should be 250 days. There’s no obvious reason to me that these should be correlated, other than a tendency to say “Time Served” on the part of the judge could tend to anchor a number of sentences near the average.

It’s a flow argument. Population A in pretrial detention, every day A/51 flow through to trial and actually-sentenced prison (/jail, I’ll pretend they’re the same thing from now on). Population 4A in prison. If the prison population isn’t changing too fast (which is another assumption that might fail), that suggests the rate that people *leave* prison is roughly A/51 or 4A/204, so the number I should have used was 200, not 250.

…but I completely ignored the people going to prison not from pretrial detention. If half of people on trial aren’t detained beforehand (per the article), then we get 2A/51 in and 4A/102 out, which is even lower. But I don’t think it changes the conclusion much, now we need 13/14 people (93% instead of 87%) to get not-guilty or no prison.

Unless I’ve made another mistake? Someone who is good at math help me my prison population is exploding.

That does sound pretty weird to someone from the UK, for whom those words are synonyms. I’m aware that they do mean different things in the USA, but I’ve never managed to get a firm grasp on exactly what the difference is.

Jails are managed at the local level and mostly used to hold people for minor offenses or while awaiting trial. They’re usually (though not always) relatively small, and often located in or near a courthouse or police station. Prisons are state or federal and mostly used for long-term confinement; they’re usually larger, and usually standalone facilities.

As I understand it (as an American who knows only a little of the criminal justice system): Usually “jail” refers to a place where:

a. You get locked up when you’ve been arrested but not yet charged/indicted/whatever. You got into a fight in a bar and the cops showed up and arrested you and took you to jail.

b. You stay while you’re waiting for trial on the assault or drunk-and-disorderly charge.

c. You stay when you’ve been convicted/pled guilty of some local offense (city or county level stuff), typically for less than a year. So when you plead guilty and the judge gives you 30 days, you serve your sentence there.

I’m not 100% sure if those are usually the same facility or three different kinds of facility that all get the same name.

By contrast, prison is generally a federal or state level thing, and it involves longer sentences. If you kill someone in the bar fight and get convicted of manslaughter and get sentenced to five years, you’ll be serving that time in a state prison.

To elaborate, I believe the original distinction was that jails were for holding on to accused criminals awaiting trial and punishment and prisons were for punishing actual criminals after conviction. As short periods of confinement replaced e.g. fines and flogging for minor crimes, it wasn’t really practical to send them all the way upstate for a fifteen-day sentence and the rule evolved that misdemeanors (usually under local jurisdictions and not more than a year’s confinement) could be punished by a stint in the local jail. But this is still a secondary function of jails.

Hence the bit in the infographic where most of the people in local jails haven’t been convicted of anything but essentially all of the people in prison have.

Scott, all,

Here’s a link that discusses some of the contrary argument – there are studies that indicate that bail does make it more likely that defendants will show up at trial, and you can argue that the bail bond system is essentially purchasing insurance against skips – the bail bondperson accepts the premium, and is responsible for the cost of tracking down the defendant if she runs. (True, the bondsperson doesn’t have to chase the skipper, but it sounds like they usually do and usually catch them). The bondsperson also takes on the cost of evaluating defendants for likelihood of running.

https://priceonomics.com/americas-peculiar-bail-system/

Chicago Community Bond Fund is doing excellent work on this in Chicago. We are close to getting a big bail reform bill passed!

Feel free to look it up / email questions here:

https://www.chicagobond.org/

Seems to me that alternative bail systems such as DC are just begging for a different sort of abuse. People are very good at pattern matching. Prosecutors and judges are going to figure out what sort of things they can do to make the system spit out a recommendation of “no bail”. For most crimes, this doesn’t matter; career criminal gets in barfight, drug gangs shoot at each other, 2-time loser is caught drunk driving again, etc; no reason to manipulate the system.

But then you get the interesting cases, where someone who isn’t a member of the underclass is the accused. Convicting such people is a much bigger feather in the prosecutor’s cap than just putting away yet another career criminal for a short stretch. And, people who aren’t career criminals are much more afraid of jail. And they have more to lose by being in jail. So when such a person appears, the prosecutor does what it takes to get a recommendation of “no bail” out of the system, and are in a winning position for the plea bargaining.

“Prosecutors and judges are going to figure out what sort of things they can do to make the system spit out a recommendation of “no bail”.”

Since the system has been in effect for forty years, and there’s still a pretty high release rate, it seems like this hasn’t happened.

I’m not saying they’ll do that all the time. I’m saying that if local troublemaker Bob Nogoodnik gets involved in a barfight and gets pulled in on an assault charge, he’s got every chance of getting out pre-trial. The prosecutor doesn’t care about him.

On the other hand, if well-heeled Jim Cleancut gets involved in similar trouble (maybe he’s a mean drunk, or maybe he was just in the wrong place at the wrong time)… here’s a guy the prosecutor can make an example of to show he’s Mr. Law-n-order. For starters, he can charge him for aggravated assault rather than simple assault; maybe it won’t stick, but it’ll change the input to the release/no-release algorithm. Now let’s see, Jim’s got considerable financial resources; he’s got family in other states, he went to school clear across the country… sure looks like a flight risk. Lock him up!

I’m of the opinion that the real injustice here is the statistic that 96% of guilty verdicts come from plea bargains. The ability of prosecutors to coerce guilty pleas out of defendants through the plea bargaining process is a violation of the right to a trial by jury, plain and simple.

96% of guilty verdicts coming from plea bargains, is entirely consistent with 96% of guilty verdicts being actually guilty people who are “coerced” by prosecutors who could – legitimately, fairly, and with full due process – secure their conviction and probable X year prison sentence, instead offering them 0.75X if they accept responsibility and incidentally save the state the bother of a trial.

There’s room for injustice in the system, but the 96% number is not evidence of it. In a properly-functioning criminal justice system, almost all arrests should be settled by either a dismissal of charges (when the prosecution realizes they will lose if they go to trial) or guilty plea (when the defendant realizes ditto). Actual trials should occur only when some freakish arrangement of facts leaves the case balanced on the knife edge of reasonable doubt, or when someone is being pointlessly stubborn.

96% strikes me as a bit too high of a number for this, but I concede that I have no idea what the ideal number actually SHOULD be.

I don’t believe that 95% of people who the police arrest and who prosecutors take to trial are guilty. But you could probably sell me on 75…

If I recall correctly, about 80% of jury trials where it’s in question produce a guilty verdict. But that’s the last stage of a process designed to weed out the clearly guilty (via guilty plea) or the probably innocent (via dropping charges). And charges do get dropped pretty often, or are never brought up — I’m not sure of the formalities, never having been arrested myself, but I know a number of people who’ve been brought in by the cops, then let go within a day or so.

In all the juries I’ve ever served on, for what it’s worth, the defendant was obviously guilty as hell and the only real question was what exact charges the offense counted as. But that’s a small number of juries.

Why would any defendant agree to a plea bargain? If they were innocent, because they were intimidated. If they were guilty, in exchange for a lesser sentence than their crime deserved.

So plea bargaining requires either punishing the innocent, or going easy on the guilty. But it gets the conviction statistics up. It certainly makes it look like you are being tough on crime.

Trials are expensive. If you have some amount of money for a justice system, you may prefer to spend it on cops and prisons than on lawyers and judges, and a well-functioning plea bargain system facilitates this.

Plea bargaining (like the whole justice system) is a tradeoff between a bunch of different goals–justice for the accused, public safety, efficiency of the justice system, etc. What I think we need to know is: what kind of tradeoff are we making right now? How would we know if we were making a bad tradeoff?

For example, what fraction of people in prison right now (mostly plea-bargainers) are innocent of the specific crime that sent them there? What fraction are innocent of any serious crime, and the cops just flat got the wrong guy? Getting some kind of handle on those numbers would help us know if we were making a bad tradeoff.

Suppose we could somehow determine that nearly everyone in prison was guilty. Then stuff like getting rid of plea bargaining or improving standards of evidence for criminal cases wouldn’t seem too urgent. On the other hand, suppose we could somehow determine that a substantial fraction (say 10%) were innocent. In that case, we’d want to slide the tradeoff-bars toward more justice for the accused and less efficiency.

The plausible estimates I’ve seen were:

The innocence project quotes a news article estimating that at least 1% of prisoners are innocent.

This article based on a survey of a bunch of people involved in the justice department suggests about half a percent of prisoners are innocent.

If those are at least approximately right, then that gives us a sense of the size of the tradeoff–probably 99% or so of prisoners are guilty, which suggests to me that it’s probably hard for us to improve a huge amount on our rate of locking innocent people up.

If we were looking at 10% innocent people locked up, I’d think we could do substantially better, but for a process as fundamentally noisy and hard to get right as criminal justice, it sure seems like getting the false-positive rate down from 1% to, say, 0.1% (1/1000) would be pretty hard.

On the other hand, I don’t know how much weight to give these estimates. Anyone have better data?

One terrifying piece of evidence is the Roman-Walsh-Lachman-Yaner study. They found a county in Virginia where the forensic sciences lab never threw anything out and therefore had hundreds of samples of semen, blood, hair etc left by rapists from the 70’s and 80’s. In 227 of these cases, a person was convicted of the rape, and they were successfully able to run DNA tests on both the old sample and the convict. In 40 cases, so 18%, they didn’t match.

Note that there is no obvious selection bias here — they looked at every case in this county and filtered based on whether they could do the test, regardless of other evidence for or against the convict.

Obviously, these particular errors wouldn’t be made today, but it suggests the rate at which errors are being made.

Preferably going easy on the guilty.

Making sure each and every guilty scumbag gets exactly what they deserve is hard. Batman hard. And bloody expensive, with some of the cost literally paid in blood, and some in wrongly convicted innocents, and lots of it in taxpayer dollars. If you insist that Every Guilty Scumbag Gets Exactly What They Deserve No Matter The Cost, you’ll wind up getting what pretty much everyone who ever said “…no matter the cost” gets.

If you’re trying to put a cap on the costs, going easy on the criminals who are willing to plead guilty seems like a really obvious place to start.

Unfortunately, this also tends to push the system towards more harshly punishing the innocent. Erroneously convicted innocent defendants will get a harsh sentence compared to plea-bargaining guilty defendants. And I would guess that a guilty defendant is more likely to take a plea than an innocent one. Piling on additional penalties for defending yourself tends to lead to injustice.

At some point plea bargaining begins to look like a high-stakes game of chance against an opponent with an infinite bankroll. Sure, you think you have a good hand, but if the cost for folding is 6 months in jail and the cost for losing is a 5 years in prison and a felony conviction, what odds do you need to place on winning to make going to trial a rational choice?

Erroneously convicted innocent defendants who don’t accept a plea bargain will get a harsh sentence compared to plea-bargaining guilty defendants.

Whether or not someone accepts a plea bargain would seem to depend mostly on A: whether they are one of the edge cases where the evidence at hand leaves the outcome of a trial highly uncertain, B: whether they are irrationally stubborn in light of A, and C: whether they are receiving good legal advice.

A and B would seem to be independent of whether the suspect is innocent or guilty; I’d expect innocent suspects to get at least marginally better legal representation than the guilty but maybe not the edge cases from A. So I don’t see this as a source of inherent bias against the innocent, and I think you are not playing fair when you consider only two of the four relevant groups (excluding the innocents who take plea bargains and the guilty who go to trial).

@John Schilling

I’m assuming innocent people… being, you know, ACTUALLY INNOCENT… are ceteris paribus much less likely to be willing to accept a plea than guilty people.

This isn’t clear since plea bargains are made in the shadow of what would have happened at trial. Trial is risky and imposes costs on all parties so the efficient outcome is for everyone to settle before trial to an outcome that makes them better off, on average, than if they went to trial.

If the numbers in the post are accurate, charity is a poor way to solve this problem. Good old reliable greed should be more than enough!

Whether the cost of keeping someone out of jail is $1 or $10 a day, either amount is far lower than a day of labor. So it should be quite profitable for an individual, or a company, to cover bail in exchange for labor.

The more interesting question is: what’s the cause of this market failure?

uber-for-bail-bondsman startup incoming!

lets go, someone toss me $500 million

1. These people aren’t employed.

2. They are too risky to employ. 2% of them will commit a violent crime obvious enough to get arrested for. 9% of them will commit some other crime obvious enough to get arrested for. Who knows what other crimes they will do that won’t be immediately noticeable.

It’s possible that “being employed” will cut down on their rate of crime, maybe significantly, but someone who decides to test this is going to be taking a big big risk.

Minimum wage, perhaps? I don’t think labor law considers “not being in jail” as part of a worker’s compensation. And there’s probably other legal issues that you can run afoul of when you’re negotiating with someone in jail, which is probably the most unequal bargaining position I can think of. Maybe you should take this over to /r/legaladvice, they love crazy hypotheticals like this.

But legality aside, I’d also suspect that there’s just too much volatility. If your labor supply comes from people bailed out of jail, then it’s hard to predict when you’ll have someone available to work (because that depends on how often people get arrested and can’t make bail) and when they will stop being available (which depends on their court date, and if they decide to flee). Court dates are supposed to be within 45 days of the arraignment, according to a quick Google. So I’d predict this will only be useful if you have work that doesn’t need any special skills, can be started up with little training time, and can either be completed in about a month, or transferred to another laborer for little cost. Even before you factor in the risk of hiring accused criminals, I’m not sure how many businesses fit the profile.

I want someone to make a convoluted connection between Scott’s article and this viral piece on millennials spending too much on avocado toast to afford their own house: http://time.com/money/4778942/avocados-millennials-home-buying/

Unless you’re seriously suggesting that giving people bail is more efficient than buying third-worlders malaria nets, why in the world would anyone “in the effective-altruism sphere” come near this? Also, I don’t see any EA-based justification for limiting this to the US. Surely there are third world countries where people need bail amounts that are, because of poverty and exchange rates, paltry compared to American bail and where your bail money can go farther (and where prisoners may even be more likely to be innocent, because of corruption).

By EA standards, this proposal is buying warm fuzzies, not utilons.

(Note: I am not EA. Just pointing out a seeming contradiction here.)

The primary cost of bailing someone out is the system to deliver the money, rather than the money itself, which gets recycled. I’d expect that the cost of finding someone who is familiar with Impoverished Country X’s legal system and lives in that country, getting your money exchanged, and so on raises the overhead to impractical levels for a US-based charity.

In other words, if Impoverished Country X has its own version of the Bronx Freedom Fund (and a website to donate to), it might well be a worthier cause. But it doesn’t follow that the Bronx Freedom Fund should pack up shop and move its operations there.

Think of it as EA-lite. Sure, it’s probably not the maximum good you can do per dollar. But there are lots of people interested in “criminal justice reform” in the US. Perhaps Scott is merely suggesting that *these people* could do *much more good* towards their stated aims by paying peoples’ bail?

I’m not an EA, but if I could keep a person out of jail for a dollar a day, his labor each day would be worth at least two orders of magnitude more than that. It won’t be hard to get that dollar back out in some way.

Assuming the people who want to be bailed out are employed.

And I’m sure the cost of incarcerating someone is higher than $1/day, so you have to wonder why the government doesn’t just put up the money itself.

Though your last assumption is likely false. The unemployment rate for people in prison because they can’t afford bond is very high. Especially if their normal means of obtaining income is best avoided while they await trial.

I guess this is a bit of a tangent, but I’m looking to make some contributions this year, and as a filthy nationalist I feel it’s my duty to help my fellow Americans. I’ve poked around the Effective Altruism sphere a bit and for understandable reasons there’s not many options for me. I’ve looked at several charity rating sites, but they seem more focused on measuring what % of dollars are sucked up via administrative overhead, etc., and less so about evaluating the impact of the actual work. Is there some EA-but-only-for-helping-Americans resource that I haven’t found?

PS. The Bronx Freedom Fund intrigues me, but several people here have already stated reservations about it which I somewhat agree with. Nevertheless, I may make a donation – but I would prefer to know my options first, hence this request.

A note on this part

Because you get bail money back this might be the correct number, where every $39 they get allows them to cover on average bail for one more person.

This checks out. If you get 90% of the money back (i.e. average of getting all the money back 90% of the time), then the expect bail-payouts from $39 is 39/(1-9/10) which is $390 dollars, if successfully repeated ad infinitum. Given Scott’s numbers, that’s a very reasonable ballpark of a low-ish bail dollar value.

Is it correct to assume that the bail money posted for those who do not turn up at the court date goes to law enforcement/the courts/someone else who is in a position to increase the bail prices? If that is so, surely giving money to a charity that pays people’s bail will essentially amount to guarantee them payment of whatever price they ask, removing any incentive they might have to keep bail rates down: in other words, an instance of tulip subsidies.

“If you grant 1, wouldn’t the easiest way to solve these problems and make everybody everywhere happy be to…just reduce the frickin’ crime rate somehow?”

Well, where would be the challenge in doing something so simple and easy?

I agree that jail shouldn’t be harsher than necessary and that the bond system may not be very efficient, but so often these calls for prison reform come across not just as worried about abuse or innocents falling through the cracks, but as being upset that actual criminals are in jail. From this article, for example:

“People in jail have a bad habit of making incriminating statements that get reported and used against them on trial.”

Is that really a bad thing for society on net?

edit: As others have said, the bigger problem is that there’s so much crime in the first place.

Remember that “don’t talk to the cops” video that made the rounds a few years ago? You can say a lot of incriminating things even if you’re innocent.

(And even if incriminating statements by a suspect are always solid evidence, it seems odd that we should gate off access to those statements by how rich the suspect is. If keeping suspects in jail to extract inadvertent confessions is a good thing, it’s a good thing independent of whether bail is.)

Also, there’s a pretty common argument that “tough on crime” sentencing strategies don’t actually decrease the recidivism rate. Or in other words, if you think that keeping a criminal in jail for longer is going to cost society more than it earns on the margin, then it’s perfectly okay to be upset that criminals are in jail.

The video is worth watching.

“People in jail have a bad habit of making incriminating statements that get reported and used against them on trial.”

A cynical person like myself might think that prisoners are extorted to claim that other prisoners confessed.

Took the words out of my mouth. Including half-jokingly describing the idea as ‘cynical’.

I seem to recall there’s some evidence for this, though. I read Barry Scheck’s book actual innocence a few years ago, and I recall it had a whole chapter on this.

Of course, it’s an old book, but I’d be a little surprised if things had gotten better.

Why should the condition that makes guilty people more likely to be convicted be applied disproportionately to people who are broke?

Correlation or Causation?

What if people who make the kind of bad decisions which lead to being broke are more likely to also make bad decisions like committing crimes?

I don’t see a correlation vs. causation question?

You’re assuming that not making bail causes a person to be more likely to be convicted. But what if people who can’t make bail are simply more likely to be guilty?

Only way to be sure: randomly deny or grant bail.

Or to put it a slightly different way, being so broke you have absolutely no way to raise $200 signals a high level of irresponsibility, such that I am unlikely to desire to help any such people, regardless of whether or not they may be criminals.

I know plenty of poor, lower-class people who could come up with that sort of money if they absolutely had to (and “absolutely had to” does not include “someone administering a survey asks you if you could”)

I’ve often seen certain types of pro-market capitalists accused of viewing the market as an arbitrator of moral worth, and I’ve typically considered those accusations to be accurate, but I’ve never seen the principle stated outright and so boldly.

Your options change pretty dramatically once you are in prison. Bail might not be set for several days (Friday arrest) which can eliminate a couple of options (finding any job that pays cash, or getting an advance from your employer), and once in prison getting bailed out takes several hours of someone else’s time which comes at a cost. Lots of other compounding factors are possible like getting arrested out of state.

I do worry that sentences are really, really long. If I’d never heard of our current sentencing guidelines and was asked to invent them out of thin air, I think I’d give about 10% of the real value for most things. I think this is different from “criminals shouldn’t be in jail”.

I suspect you’re right, but how can we figure out how long a sentence should be?

In terms of deterrence, I suspect long sentences aren’t all that effective, because I doubt the folks committing the crimes are really thinking 20-30 years into the future. (That is, I suspect a 15 year sentence ~= a 30 year sentence in deterrence terms, for most criminals.)

In terms of incapacitation/quarantine, I think most violent criminals age out of violent crime by the time they’re in their 40s-50s, so we’re probably not being made enormously safer by keeping a 60-year old guy in prison for that armed robbery/murder he committed when he was 19.