I.

German Lopez of Vox writes that “America’s criminal justice system has in many ways become a substitute for the US’ largely gutted mental health system”.

He says that starting in the 1970s the US “began locking up a lot more people”, and “at the same time, the country pulled back and defunded its public mental health system”. He admits that “this wasn’t, at the time, totally malicious”, but then says it “left the criminal justice system as the only system that can respond to people with mental illness.”

He concludes that as a result, “the number of people with mental illness in prisons/jails outnumber those in state hospitals 10 to 1.” The apparent (though unstated) conclusion is that defunding the big state mental hospitals was a mistake and we need to bring them back so that the mentally ill in state hospitals once more outnumber those in prison.

Lopez seems to be working off a model where there is a population of mentally ill people who can’t make it in normal society, and so will inevitably end up either in a long-term mental hospital or a prison. Since mental hospitals are good places where people get treatment, and prisons are bad places where people get punishment, we should “catch” these mentally ill people before they end up in prison so that they can be in nice hospitals instead.

Needless to say I disagree with pretty much every part of this assessment.

II.

Between all of this talk of “the tragic collapse of America’s public mental health system” and “the US’s largely gutted mental health system” and “the country pulled back and defunded its mental health system” and so on, you might get the impression that less money is being spent on mental health. This is not really true. The share of GDP devoted to mental health is the same as it was in 1971, although this looks worse if you compare it to rising costs in other areas of health care. There hasn’t been a “gutting of the mental health system”, there’s been a shift from long-term state-run mental hospitals to community care. It hasn’t “left the criminal justice system as the only system that can respond to people with mental illness”, it helped create an alternate and less restrictive system of outpatient psychiatry. In my opinion, this was a positive development, and the share of mentally ill people in prison is not an argument against it. Let me explain.

“Mentally ill people in prison” conjures up this lurid image of psychos who snap and kill their families, followed by “well, what did you expect leaving a person like that on the street?” The reality is more mundane. There are lots of mentally ill people in prison because there are lots of mentally ill people everywhere. Remember, 20% of the population qualifies as mentally ill in one sense or another. If a depressed guy sells some marijuana and gets caught, he is now a “mentally ill person in prison”.

There are disproportionately many mentally ill people in prison partly because people’s illnesses lead them to commit crimes, but mostly because some of the factors correlated with mental illness are the same factors correlated with criminality. Poverty? Check. Neighborhood effects? Check. Genetic load? Check. Education? Check. IQ? Check. Broken families? Check. Drug abuse? Definitely check. The factors that gave that pot dealer depression might be the same factors that drove him to sell pot instead of becoming an astronaut. Treating the depression might help a little, but it’s not guaranteed to keep him on the good side of the law.

In my model, the overwhelming majority of mentally ill people can live okay lives outside of any institution, hopefully receiving community care if they want it. If they commit crimes they will go to prison just like anyone else; if not, we should hardly be clamoring to bring back the often-horrifying state-run mental hospitals and lock them up there.

So when we talk about the number of mentally ill people in prison, we should be trying to distinguish between Lopez’s model and mine. That means asking: exactly how mentally ill are we talking about here?

III.

Lopez’s source for the claim that “ten times more mentally ill people are in prisons than hospitals” is a report by the Treatment Advocacy Center – note the less-than-neutral name. Where Lopez uses the phrase “mental illness”, TAC uses the phrase “severe mental illness” and defines it in two ways. For people in state prisons, they define it as reporting at least one psychotic symptom, and say 15% of people met their criteria. For people in county jails, they define it as meeting criteria for a depressive, bipolar, or psychotic illness, and say 15% of people met their criteria (they later arbitrarily increase that number to 20% because they feel like the survey might have undercounted).

No no NO. First, “psychotic” is not the same thing as “severely mentally ill”. Some people are severe but not psychotic – for example, a suicidally depressed person. Others are psychotic but not severe – for example, someone who hears a voice whispering her name but shrugs it off. Describing a survey that shows 15% of people as admitting one symptom of psychosis as showing 15% of people are severely mentally ill is really sketchy.

The prison survey provides a perfect example. It looks like the prisoners were asked fixed questions about their symptoms, and I think the exact screening instrument was just this survey, which has four relevant questions: “Can anybody else control your brain or thoughts?”, “Do you ever hear voices other people don’t hear?”, “Do you ever see something that other people tell you isn’t real?” and “Do you ever think anyone (other than correctional staff) is spying on you or plotting against you?”

Unfortunately, these kinds of surveys are really weak. I’m doing a study about this now, so maybe later I can cite myself on this, but the gist is that a lot of short mental health screening questions get false positives from perfectly healthy people. For example, I can’t tell you how many patients I’ve asked “Do you ever feel like anyone is spying on you?”, they say “Yes”, I ask “Who?” and they say “The NSA on my Internet activity”. Well, good work keeping up with the news. But a survey with a checkbox and no followup questions diagnoses that person as psychotic (see also: Lizardman’s Constant). This prison questionnaire was smart enough to exclude prison guards, who are certainly spying on all the respondents, but even beyond that I feel like the criminal lifestyle really does involve being spied on and plotted against a lot. At the very least it gives you lots of opportunities to legitimately worry about it.

(also, the diagnostic criteria for psychotic disorder are very clear that paranoia experienced while taking drugs doesn’t count. 75% of prisoners admit to using marijuana, marijuana can totally make you paranoid, and as far as I can tell the survey did not specify that the paranoia had to be while sober.)

(also also, Scientific American says that about 5-15% of perfectly ordinary people hear voices. Meanwhile, 4-6% of prisoners in the survey admitted to it.)

When the survey says that X% of prisoners have felt plotted-against or heard voices in the last year, does that mean X% of them are psychotic? That X% of them are “severely mentally ill”? That the old state mental hospitals need to be re-opened so X% of them can be locked up there for being too crazy for society? I don’t think it means any of those things.

But this is the stricter of the two criteria that the survey uses! The other one counts depressed people, bipolar people, and psychotic people. I don’t want to trivialize non-psychotic illnesses like depression. But remember: about 10% of the ordinary non-prison population is depressed/bipolar/psychotic. Also, going to prison is depressing as heck in and of itself. When they say that 15% of people in county jails (rounded up to 20%) are severely psychiatrically ill, they’re talking about pretty normal people, who might be in prison for something unrelated to their mental illness and might not even have become mentally ill at all if they hadn’t been incarcerated.

So I don’t think this survey shows the majority of the mentally ill prison population is in need of institutionalization. Yes, ten times more mentally ill people are in prison than in state mental hospitals, but consider the base rates! The prison population is huge. The population of people who need to be committed to mental hospitals 24-7 is tiny. Even if mentally ill people committed crimes at exactly the average population rate, there would still be far more mentally ill people in prison than in psychiatric hospitals, just by base rates! Especially if you use as broad a definition of “mentally ill” as these people!

So when Vox says that ten times more mentally ill people are in prison than in psychiatric hospitals, I will shoot right back at them that ten times more mentally ill people are in the Los Angeles metropolitan area than in state mental hospitals. You want more meaningless statistics? Ten times more mentally ill people are in the Southern Baptist Church than in state mental hospitals! Ten times more mentally ill people watched the last season of Game of Thrones than are in state mental hospitals! We can’t and shouldn’t aim to institutionalize all of them.

IV.

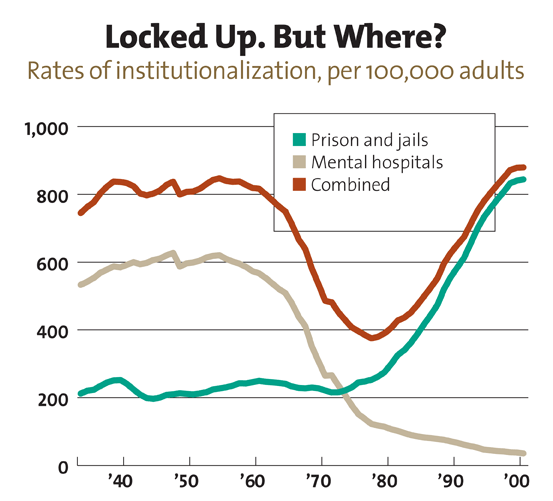

What about that graph? It’s very suggestive. You see a sudden drop in the number of people in state mental hospitals. Then you see a corresponding sudden rise in the number of people in prison. It looks like there’s some sort of Law Of Conservation Of Institutionalization. Coincidence?

Yes. Absolutely. It is 100% a coincidence. Studies show that the majority of people let out of institutions during the deinstitutionalization process were not violent and that the rate of violent crime committed by the mentally ill did not change with deinstitutionalization. Even if we take the “15% of inmates are severely mentally ill” factoid at face value, that would mean that the severely mentally ill could explain at most 15%-ish of the big jump in prison population in the 1980s. The big jump in prison population in the 1980s was caused by the drug war and by people Getting Tough On Crime. Stop dragging the mentally ill into this.

Lopez himself wrote a nice piece on how most mentally ill people are not violent, and another nice piece on how most people in prison are there for violent offenses. But put these together, and you get that most mentally ill people do not end up in prison. Most of the people who got out of the mental hospitals during deinstitutionalization are getting by. Some of them are homeless, and that’s bad. But if you want to solve homelessness among the mentally ill, build homeless shelters, not state-run long-term mental hospitals.

V.

In case you haven’t noticed, I really don’t like state-run long-term mental hospitals. There is a really amazingly great thing about prison, which is that you don’t go there unless you’re convicted of a crime. Mental hospitals do not have that advantage. The commitment process kind of sucks, and I am saying this as a person who makes commitment decisions myself. A lot of times it degenerates into a ritualized method of avoiding lawsuits without much concern for benevolence or patient autonomy. It helps me sleep at night to know that most commitments only last a couple of days or a week at most. Long-term state-run mental hospitals didn’t work that way. Remember that some of the perfectly sane people in the Rosenhan experiment were kept locked up for fifty days just for saying they heard a voice once but now they’re better.

I think long-term state-run mental hospitals are better than prison, but not by very much. The Rosenhan participants described it as:

…an overwhelming sense of dehumanization, severe invasion of privacy, and boredom while hospitalized. Their possessions were searched randomly, and they were sometimes observed while using the toilet. They reported that though the staff seemed to be well-meaning, they generally objectified and dehumanized the patients, often discussing patients at length in their presence as though they were not there, and avoiding direct interaction with patients except as strictly necessary to perform official duties. Some attendants were prone to verbal and physical abuse of patients when other staff were not present. A group of bored patients waiting outside the cafeteria for lunch early were said by a doctor to his students to be experiencing “oral-acquisitive” psychiatric symptoms. Contact with doctors averaged 6.8 minutes per day.

The idea of potentially saving a couple of people from prison by pre-emptively committing way more people to a mental hospital does not appeal to me at all, and I still think closing the institutions was the best thing Reagan ever did.

But prison and institutions aren’t the only two options! There’s a six month waiting period for psychiatrists in most parts of the country. The existing mental hospitals – which are different from and often nicer than the old state-run institutions – are constantly turning away people who want to be there because they don’t have enough beds for them. There are a bunch of patients who are having trouble affording their medications. There are special treatment options like day clinics, partial hospital programs, recreational therapy, occupational therapy, et cetera that do really great things but which most patients can’t afford. There are intensive health monitoring programs – think nurses who come to your house and make sure you take your medication on time – which are proven to improve outcomes but which never have enough staff for everybody who needs them. There are omnipresent underfunded community mental health systems. All of these things are doing great work right now. Indeed, the plan for closing the state-run long-term facilities was to gradually transition care to all of these other systems, and where that was supported it worked well, and insofar as it didn’t work well it was because it wasn’t supported.

If we support all that, will it keep all mentally ill people out of the prison system? No. First of all, no treatment is perfect and most are downright mediocre. Second of all, like I said, there are mentally ill people in prison because there are mentally ill people everywhere. There are disproportionately many mentally ill people in prison because the risk factors for mental illness are the same as the risk factors for crime, like poverty and drug abuse. Regardless of the level of care given, mentally ill people are likely to end up in prison at increased rates, unless you’re willing to either institutionalize all mentally ill people before they can commit any crimes, or excuse all crimes committed by mentally ill people.

But we shouldn’t be making our mental health decisions based on worries about criminality and prisons. Most people who are mentally ill will never end up on the wrong side of the law, and many (most?) mentally ill people who do end up in prison will do so for reasons not directly related to their illness. Make mental health decisions because it’s the right thing to do and there are people who really need help.

And if mentally ill people do end up in prison? There is a forensic health system dedicated to treating mentally ill prisoners. It’s not perfect, but with more funding and attention it could be better. There are forensic psychiatric hospitals that house mentally ill prisoners, and though again they are not perfect, they at least have that great advantage that you can’t be put in them unless you are found guilty of a crime.

So my argument is: fund and use the community mental health system more to help people in the community. Fund and use the forensic mental health system more to help people in prison. But stop acting like the two groups are fungible. And stop trying to institutionalize more people. That doesn’t help.

You had me until I saw the name Rosenhan.

Things went rapidly downhill after that.

I have written my representatives about this topic. There a people that end up in jails for mental illness who are NOT criminals. They may have one psychotic break and get picked up and put in the prison system. And as adults it is hard to even find out where your loved one is. It is sad and uncalled for and must be changed if we are a caring nation. It was a huge mistake to get rid of so many mental illness hospitals thinking that new medications would solve the mental health problems. That was hardly the case. I don’t believe there are even enough mental health workers to take care of all those who need the help and it is very expensive for many to get that help. It takes more than one visit to get proper therapy.

I don’t know for sure the statistics for mh patients in prison but tnis news report from California is very disturbing: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-HcjjUL7Q7g&ab_channel=FredMamoun

Did I really read “if the mentally ill want help?” Mentally ill people don’t have the capacity for logical decisions, ie listening to the voices in their heads and eating a part of their arm, or throwing their baby in the river. These people are going to ask for help?

Totally agree with the observation that the criminal justice system exploded when the mental health institutions imploded. Community mental health systems only handle the treated mentally ill in a less serious state of mind. Let’s reinvest in more humaine mental health institutions. My fear however, is that they will be staffed or understaffed much like our growing nursing homes for the aged.

There are degrees of mental health problems.

Someone can be suicidally depressed yet still have capacity to make treatment choices though their degree of capacity may vary from day to day.

There have been court cases where anorexic patients have been declared competent to choose to refuse treatment because they’ve demonstrated that they fully understand the consequences (death).

Saying that all mentally ill people don’t have capacity is like saying that all Orthopaedics patients can’t walk. Some can’t but some can. It depends.

It is somewhat misleading to say that most prisoners are in prison for violent crimes. A large number are there for drug crimes that have been “defined” as violent simply due to the amount or kind of drug involved, without regard to whether any actual violence was involved. These people populate the spectrum outlined by the author, but drug addiction is a primary reason for these offenses. In my part of the country, the attention to addiction has not reached the level I have seen described in most other nations with higher rated health care systems. In fact, the treatment is usually found in prison.

Also, there’s a shitload of people in prison and jails who wouldn’t be there if they hadn’t violated probation/parole with drug use. The statistics will, more or less properly from a legal perspective, say those people are imprisoned for the original offense that may not be drug related, but practically speaking that’s only a part of the story.

Do you have statistics to show this?

“Lopez himself wrote a nice piece on how most mentally ill people are not violent, and another nice piece on how most people in prison are there for violent offenses. But put these together, and you get that most mentally ill people do not end up in prison.”

These claims may all be true, but the fact that most mentally ill people are not violent and the fact that most people in prison are there for violent crimes, do not in themselves imply that most mentally ill people do not end up in prison, as you seem to be implying is the case.

Checklists are useless except as a reminder of what areas to explore. Horoscopes and fortune cookies evoke the same kinds of endorsement. As for the horrors of jail, I recall a particular patient who kept going through the revolving door when I was a young inpatient psychiatrist. I never saw him free of psychosis. He disappeared for about a year, returning to clinic with no active psychosis. He had been serving 11 and 29 in county jail. A month later, he was back on the ward, using drugs and psychotic. Was he mistreated by the judge who locked him up instead of sending him to the hospital?

Drug induced psychosis? The prison making sure he takes his meds? Or lack of medical insurance for meds outside of prison? Other?

Just wanted to let you know, this article changed my mind. I’ve spent some time around mental hospitals, was of the opinion that Vox espoused in the article, and this writing successfully challenged and deepened my perspective. Thank you.

I agree with much of what you say, but:

>The share of GDP devoted to mental health is the same as it was in 1971, although this looks worse if you compare it to rising costs in other areas of health care.

This is the problem I have. First, as you point out mental health as a share of total health care costs has gone down. Since the price of hours-with-a-provider has gone up across the board since the ’70s (relative to GDP too, I think) this indicates less care is being provided total.

Second, perhaps the same share of GDP is being spent on mental health care in total–but more of that share is rich people/rich people’s insurance spending money on the mental health of the people who are already best off. Meanwhile, it’s an obvious fact that since Reagan, less of the government’s money is being spent on mental health care for people who can’t afford it on their own.

There’s really no way to tell from anything you say what percentage of mentally ill people in jail or on the streets are there because they’re mentally ill. What you say is almost as speculative as what the Vox guy says. It’s entirely possible, for all you say here, that the present-day situation is worse for the mentally ill than in the days of state hospitals, and that it’s worse because the state hospitals were closed.

I’m posting from my phone since I’m at work, so I hope I may be excused for not being as eloquent as I’d hope to be otherwise.

While I don’t see anything to disagree with in your criticism of the Box piece, I did want to point out an important issue that you kind of skip past. You say in your last section that “there are forensic psychiatric hospitals,” but that’s not universally true. My state of Virginia does not have any for juveniles. This means that if you are arrested and/or convicted of a crime and are under 18, you get sent to the regular juvenile penal system, no matter your mental state. Of course, those facilities are not remotely equipped to deal with someone with, say, full-blown schizophrenia. No one in state government seems willing to fix this, since it involves spending money on people, and we’re not really about that. Even though a member of our legislature was stabbed by his mentally ill son, who was only at home because there were no beds available for emergency admissions.

So again, I don’t think this undercuts your overall argument, but I wanted to point out that there are not necessarily the treatment alternatives for those who have broken the law that you mention. As you say, mental health programs are criminally underfunded, and this regrettably leaves jail as the only option in some cases.

I also think you understate the legal process centered around involuntary commission. I don’t disagree regarding the fact that long-term hospitalization can become indefinite. But the initial process does involve more procedural safeguards than you suggest, including a hearing with a right to a lawyer (with one being appointed at the state’s expense if need-be). This is often more than is given to those languishing in jail because they can’t afford to make bail. Not exactly a laudable comparison, but nonetheless the process is not as draconian as you say.

It’s rather unfortunate that The Last Psychiatrist deleted “The Terrible, Awful Truth About SSDI”, because that would seem the perfect companion to this piece.

Is it the Wayback Machine, I wonder?

It is https://web.archive.org/web/20101129141646/http://thelastpsychiatrist.com/2010/11/the_terrible_awful_truth_about_1.html

I’d have to check again, but I remember there being a number of good TLP articles that are no longer on his site, but still show up in the Wayback Machine.

Looks like it’s reprinted here:

http://davidmarsden.tumblr.com/post/47216977797/the-terrible-awful-truth-about-ssdi

>There are forensic psychiatric hospitals that house mentally ill prisoners, and though again they are not perfect, they at least have that great advantage that you can’t be put in them unless you are found guilty of a crime.

Unless you’re being held there to evaluate your competency to stand trial, which is 30 days at a minimum.

Also, something like 90% of felonies never go to trial; they’re plea bargains. Let’s say your roommate gets caught with drugs and guns, and because you were in the apartment you also get charged with possession of both. Pleading guilty to drug possession might look good if it buys you safety from the gun charge.

..But yes, better community services, please.

Since this blog is keen on writing tips, I have two:

1. Commas and periods go INSIDE quote marks, not outside.

2. It goes without saying why “needless to say [something I’m going to say anyway]” is bad writing. See what I just did there?

re: #1, not necessarily. It’s a British thing, and many experts prefer them to go outside. (And IMO it does make sense: the period marks the end of a sentence, and should be at the end.)

See Steven Pinker’s wonderful “A Sense of Style”, for example. Or here is an interview in which Pinker defends, among other things, the outside comma/period.

I typically put them outside when they’re not part of the quote. It just makes more sense.

I also put them outside with “scare quotes” or “terms of art”, since I think it looks silly to put them inside, as if the comma were part of the quoted phrase.

Re: #1: That rule is dumb, and I decline to follow it. I’m glad to see other people also ignoring it.

(I like Pinker’s quip: “Messing up the order of delimiters in a way that doesn’t reflect the logical nesting of their content is just an affront to an orderly mind.”.)

(See what I just did there?)

Now I’m in an impossible bind: having been taught from a young age that commas and periods always go inside quotation marks, putting them outside looks disorderly and wrong. But logically it makes sense to put them outside when they’re not part of the quote.

When it’s something like “John said, ‘I’m going home,'” I put it inside of the quotes.

But when I’m putting quotes around a “term of art”, then I put it on the outside.

When writing plain English, I do the old-fashioned rules of usually putting the punctuation inside.

But too often I’m talking about computer syntax, and I can’t tell the user to make their username “George.” Because is that 6 or 7 characters?

It looks weird to shift back-and-forth, so if I have any quantity of computer code I shift to the other usage.

I like this. When the quote is a full sentence, then it deserves its own punctuation, which should not affect any of the normal punctuation in the sentence in which it is embedded.

Luckily for people like us, English doesn’t have a formal authority, so we can do what we like.

I noticed that Scott’s parentheticals did not start with capitals. Is he trying ot pass off “(” as the first letter of the sentence?

I thought “(” was a capital 9.

Re #2: the phrase exists for a reason or it wouldn’t be a phrase. It can be overused, or used badly, but it’s not bad writing on its own.

More specifically, it’s perfectly normal in popular writing to occasionally mention things the reader already knows. Wouldn’t it be nice to have a way of saying you’re doing that?

“needless to say” signals “I think most of my readers know this but for the few who don’t…”

Or, alternatively, “there are several valid conclusions that can be drawn from what I have just said. I don’t want to insult your intelligence by suggesting you haven’t gotten it already, but the one I want to use to further my argument is X.”.

I deliberately countersignal against the punction-inside-quotations rule, and so should all of you up until such time as it would endanger the effectiveness of my countersignalling strategy.

I’m a level 5 contrarian, I don’t have any opinions held by more than 6 people.

The Wikipedia discussion of this subject.

Reminder that Strunk and White’s classic “Elements of Style” includes Strunk’s wonderful rant against the phrase “the fact that…”

I have found some rare rhetorical-flow uses for “the fact that”, but for the most part I’ve agreed with its removals.

The one that’s blown my mind recently is that punctuation is meant to be placed after the parentheses.

Any mention of Elements of Style now reminds me of Geoff Pullman’s takedown.

Thanks for the link. I read Elements long after my grammar education was over, so while I found it fun to read for its distinct personality, I don’t think I actually picked up any grammar issues from it.

Why do you think so many writers say things like “needless to say”, if it’s bad writing?

I suspect that Scott used the term to serve two goals, to both smoothly lead the reader through the steps in his logic, and also to avoid insulting the reader’s intelligence. Scott has summarised the Vox argument and now is moving to his introduction. At this point, it is useful to repeat his position. But since his post heading and earlier bits implied his position, Scott suspects his modelled reader, being intelligent, will already know he disagrees. The ” needless to say” is a nod to that intelligence. Plus, a not-so intelligent reader can get a useful recap they might need.

There are probably other ways of achieving the same goal, with their own trade-offs. There is perhaps an even better potential way out there that might make the difference between a Scott and a Shakespeare. But, that doesn’t mean that Scott’s choice of wording is actually redundant.

Commas and periods go INSIDE quote marks, not outside.

“That’s not how I learned to do it”, she typed. 🙂

“I’M NOT A PART OF YOUR SYSTEM”!

I’d like to take this opportunity to ask what the deal is with “private prisons.” They seem to be a progressive bugaboo lately, as well as a talking point about why “some things just can’t be privatized,” yet I don’t actually know of any private prisons that actual criminals have been sent to, or, if they are prevalent, why they are supposed to be so evil. I’ve seen Facebook memes showing crowded bunk beds, but I’m not sure that that is any worse than all the shanking tv and movies tells me goes on in non-private prisons?

They’re fairly clustered in certain regions. You wouldn’t be surprised which ones, so if you don’t live in those areas you’d never hear about them even if you did have reason to hear about particular prisons (which obviously most people don’t).

Although certain private prisons have been called out as particularly subpar, I think the main thing most progressives worry about is giving a private company an incentive to increase or at least maintain the prison population, plus concerns about rehabilitation, all within the general context of progressives not assuming that the private sector is intrinsically more efficient. Speaking for myself, I don’t assume that the average private prison is notably lower in quality than the average state prison, but I still think it’s an awfully bad idea because of those incentives.

“giving a private company an incentive to increase the prison population”

What about the government’s incentive to increase the prison population?

Far far less explicit.

The state has mixed incentives. Their voters want lower taxes and that has to be balanced against other desires.

With the company the only thing the company shareholders want is more money. This can be achieved through careful lobbying or corrupting the justice system. The private prison system has been caught doing both on a number of occasions with judges being given kickbacks for long sentences.

True, but prison guard (public) unions have a strong incentive to lobby for minimum sentencing laws, etc.

It seems that all companies have an incentive to increase the perception of need for the product or service they are providing. Dentists have an incentive to increase tooth decay, Burger King has an incentive to make you hungry, and defense contractors have an incentive to increase war.

I’m not saying these incentives don’t really exist, but rather that they exist for everything, so I’m not sure one can point to them as the source of any problem, nor as a reason for having the government do x, unless you want the government to do everything.

One might argue that competition is good when it’s competition to produce good things, but bad when it’s competition to produce bad things. But we don’t actually consistently produce anything most people think is bad, I don’t think: prisons seem to be “bad,” but it’s actually the needing of prisons which is bad. One might say, “okay, then don’t give companies an incentive to create things the needing of which is bad.” But by that logic we should expect private doctors to create illness, private dentists to encourage tooth decay, and private security guards to cause crime, which really doesn’t seem to be a problem.

“But by that logic we should expect doctors to create illness, dentists to encourage tooth decay, etc. which really doesn’t seem to be a problem.”

It might be a problem if doctors and dentists had total 24/7 control over the lives of their patients, or if they had almost zero structural reasons to respond to the desires of their patients, or if they didn’t have longstanding professional norms enforced by both the courts and their professional organizations to treat their patients, or if the number of sick people could be simply and directly increased legislatively.

Original CC,

It seems the opposite. Unions want to maximize employment for their members, and thus are incentivized to overstate or make worse the problem for which their labor is the solution.

“It might be a problem if doctors and dentists had total 24/7 control over the lives of their patients”

I think the problem here is the mistaken perception that criminals are the “customers” of prisons. They are not. The rest of society is the “customer” receiving the service of having the prisoners kept away from them.

If there is a bad incentive, it’s to frighten the populace into thinking there is more need for incarceration than there really is (or to actually create a need for more incarceration by doing things that encourage criminality).

“If there is a bad incentive, it’s to frighten the populace into thinking there is more need for incarceration than there really is (or to actually create a need for more incarceration by doing things that encourage criminality).”

Yes, this is our concern–that private prisons will lobby for further criminalization to increase the prison population, and that they will neglect rehabilitation (which remains a proper role of the correctional system to many people even if it isn’t to you) primarily to save costs but with at least an incidental similar consequence.

@onyomi

I would argue that the smaller the number of actors the easier it is to coordinate an effective strategy to achieve their goals.

Burger King is going to be more powerful than a huge mass of unaffiliated small restaurants. Especially if lobbying helps lots of actors in the same industry but the costs are borne by just one.

Dentists have an incentive to increase tooth decay as a group and if there was one company running all the countries dental surgeries then it would be more likely they would act on that. 10,000 small dental firms individually have almost no incentive to increase tooth decay nationally. Any one dentist spending resources to increase tooth decay would benefit them all but only benefit themselves a little while carrying the costs. On the other hand individually they have a strong incentive to be perceived as advocating to reduce it.

Defense contractors actually do have a very straightforward incentive to increase war.

Incentives exist for everything but sometimes the conditions make it practical to act on those incentives.

There’s a relatively small number of actors in the private prison market. If there was a tiny private prison for every dental surgery in the country and they were all independent then I suspect that a lot of the perverse incentives wouldn’t manifest actual problems.

Eh, there aren’t that many prison guard unions either, and they have a strong incentive to increase incarceration too. And politicians always want to look tough on crime.

Heck, the whole reason there are private prisons in the first place is that we were incarcerating so many people that the regular state-run prisons were getting unaffordable. If there was a check on incarceration before, it wasn’t very strong.

Honestly the link between private prisons and increased incarceration seems pretty weak. If anything they might have an incentive to cut corners (thus being inhumane) to save costs.

I suspect private prisons are a progressive bugaboo simply because progressives tend to be against privatizing any government function, want to support public employee unions, and have a disgust reaction to people profiting from incarceration.

Prison guard unions have also been a progressive bugaboo if I remember correctly, just not recently. I swear I remember Arnold railing heavily against them at some point, but maybe calling him ‘progressive’ is stretching the word a bit.

I don’t think doctors and dentists on any individual basis have much of an incentive to increase demand for their services because it’s effectively already at max capacity as far as quantity demanded. Most of them have queues that never empty. The incentive they have is to increase capacity to pay, i.e. lobbying for greater Medicare payouts or whatever else it is that increases healthcare costs. Prison owners can much more easily build new wards than doctors can clone themselves or cut patient visit times even shorter than they already are. That sort of incentive would be more on the hospital end, but even hospitals can’t do much to increase the supply of doctors because it takes a long time to make one and most people can’t do it, though we definitely see them shifting duties to nurses and other formerly auxiliary staff that it’s easier to make more of. Staffing a prison is still much easier, though.

But yeah, prison guard unions and politicians wanting to be seen as tough on crime (and elected judges are probably about the worst on this) are just as bad as private prisons.

If anything they might have an incentive to cut corners (thus being inhumane) to save costs.

I think that this portion of your comment could serve to inform the remainder of it.

” Dentists have an incentive to increase tooth decay, Burger King has an incentive to make you hungry, and defense contractors have an incentive to increase war.

I’m not saying these incentives don’t really exist, but rather that they exist for everything,”

No, they exist for everything private. If make something public, then by default there is an incentive against it, in order to lower taxes.

That’s a remarkably simplistic way of looking at the incentives around public goods. Taxpayers have an incentive to minimize their taxes, but that couples only very weakly to any specific policy. And few people that’re getting paid out of those taxes have any such incentive — politicians sometimes might, but they have a tragedy-of-the-commons problem in that tax burden falls on the entire tax base while program benefits are more local. The latter often wins.

Outside of elected positions, everyone in government has self-serving incentives very similar to those that private actors have. An agency formed to fight, say, tooth decay may not precisely want to maximize it, but it certainly has an incentive to make it look like a serious problem, in order to secure continued funding and, ultimately, existence.

I think that this portion of your comment could serve to inform the remainder of it.

Did it not? because that’s why I included it. That there are plausible rational reasons to be against private prisons does not preclude the possibility (and frankly probability) that there are also common non-rational and tribal reasons to make it into a “bugaboo”. This is typical of most politics.

Anyway, the mistake is not noting that private prisons have some perverse incentives, it’s ignoring that public prisons have many of the same incentives (you don’t think public run prisons have pressure to cut budgets?). With the added disadvantage that it’s usually a lot harder to get redress from the government, and a lot harder to kill a dysfunctional government agency than to switch contractors.

And there is certainly a subset of people who are strongly opposed to private companies doing things that they think the government ought to do, even if (big if of course) the results are equivalent (hence “disgust reaction to profit”). Probably not a majority, but often its the least rational “tribal signaling” objections that put off the most heat (and least light).

No, they exist for everything private. If make something public, then by default there is an incentive against it, in order to lower taxes.

There is also by default an incentive for it, in order to increase the power and prestige of the civil servants who run it.

The former, tax-cutting incentive is so broad and shallow that in most cases just about every person subject to that incentive finds it insufficient to motivate action or even knowledge and so remains rationally ignorant of all the details of the subject.

The latter, scope-increasing incentive is narrowly focused on people who will find it profitable to devote most of their time to office politics focused on that goal, and these people are by definition veteran insiders in the political realm. They are surrounded by lesser civil servants who are sufficiently motivated to e.g. vote on the issue but not to carefully follow which politician voted for which statute with what consequences and will instead do what they are told by the union.

Considering this balance of incentives, is it likely that the prison system and its associated bureaucracy will grow or shrink?

The fact that private prisons aren’t more broken than. for instance, private medicine isn’t much of an argument unless you can show that private medicine isn’t more broken than public medicine. But there is evidence that it is, in the form of high US healthcare costs.

There is an argument for nationalising the more-is-bad things, and privatising the more-is-good things, because then the incentives go in the right direction in each case.

“No, they exist for everything private. If make something public, then by default there is an incentive against it, in order to lower taxes.”

I think you have it almost exactly backwards.

My relation to the government’s activity of taxing and spending is almost entirely involuntary (“almost” because my vote has a minuscule probability of changing outcomes and because I could emigrate). My relation to my dentist is entirely voluntary.

If the government does something that benefits some well organized interest group at my expense and that of almost everyone else, as governments routinely do, we have neither significant incentive nor ability to do anything about it. If my dentist does something that benefits dentists at my expense, such as advising me against brushing my teeth or putting in a crown that will soon come out, I can change to another dentist—and have an incentive to do so.

Obviously that isn’t a perfect system, because I might not realize that the dentist was acting against my interest, but it is a great deal closer than the public (i.e. governmental) alternative.

First, to clear the air–I don’t think private prisons are a relevant piece of the puzzle when it comes to explaining current incarceration rates, contra dumb liberal Facebook memes. There aren’t enough of them and they haven’t been around long enough.

Second, I disagree that the all same incentives are there with public prisons. The key, imo, is to look at the actual actors rather that trying to birds-eye-view the institutions holistically. So who are the players? First, you have the actual prison staff, up to and let’s say for the sake of argument including the warden. Public or private, all the same–they have fixed salaries/wages. They don’t receive any noticeable benefits for cost savings or reduced recidivism. Their incentive is to keep things orderly and work just hard enough to not get fired.

But who wardens the warden? In the public system, it’s going to be some high level bureaucrat in pretty much the same position. Maybe he has political ambitions and wants to be under budget to further them, but that’s a really big if. Most likely, he also just wants to avoid screwups and collect his paycheck. His boss, in turn, is a politician for whom the correctional system is only one portfolio amongst many, and who may want to save money, but is aware that no governor was re-elected because of his DOC budget. He, too, is far more motivated by avoiding the bad than seeking the good.

Contra a private system: there, the warden’s warden is much more likely to be someone with stock options, the potential for bonuses. His boss is certain to be such a person. Where everyone else is disciplined pretty exclusively by the stick, these folks also have the potential to eat some very delicious carrots.

This is, in fact, the entire appeal of the private sector–an increased ability to pass down motivations and desires from the top, rather than layers of bureaucrats whose main desire is a steady boat on calm waters. If you want a stable system that seeks, above all, to avoid screwups, you want the public sector. If you want something dynamic that will take risks in furtherance of the goal of efficiency/profit, you want the private sector. I can easily see why people would chose the latter for most things, but to me it’s clear that the former is best suited to a correctional system.

All that said, I will cop to a basic Blue-tribe disgust with getting rich off of putting people in cages. It’s not rational, but then, what is?

What sort of incentive are you thinking about?

[Edit: ninja’d by everyone; should have refreshed first. But my query about how the incentive to lobby for more punitive policies isn’t a extra source of unnecessary criminalisation, rather than an alternative one, still stands]

Could you go into more detail on that?

Do you mean ‘people will vote for get-tough policies, even when they are less effective than other ways of reducing crime, therefore politicians will respond to that incentive by enacting laws that result in more people in prison’? If so, that’s a problem, but it’s a problem regardless of whether the prison is run by the government or the private sector; whereas with private sector prisons, the ‘we get more money for imprisoning more people for longer, regardless of whether that actually enhances public safety / reduces recidivism relative to other ways of spending that money etc’ incentive would appear to be an additional problem, not an alternative one.

What have I missed?

I think a lot of the concern traces to the capacity of a private prison for converting tax dollars back into political contributions, which can have a much more directly distorting effect on the motives of individual politicians.

Unions are the biggest political donors in the United States.

I take it that “unions are the biggest political donors in the United States” isn’t intended as a non sequitur. So presumably the implication we’re to read is something like: unions already convert tax dollars back into political contributions, so there is already as distorting an effect on the motives of individual politicians. And possibly: if anything, the effect of private prisons would yield a balance of distortions.

If all anyone is worried about is the degree of distortion, and not the type, I think that’s probably more right than wrong. Both types of pressure probably serve to increase taxes. But I think there are important, justifiable differences. In particular, what unions typically lobby for affects supply and demand only indirectly, except in special circumstances (when the “market” is shrinking rapidly, for example). Teachers unions fight for fewer students per classroom, and thus more teachers, but typically don’t lobby much for more students (“Make private schools illegal!”?).*

But when a private prison has 20 empty cells, they might really need a favor *right now*. And in a state where judges are elected (making them politicians) that can get ugly in different ways than union contributions make them ugly. So the concentrating effects of wealth (and worries about losing wealth) can wind up distorting the system in different ways.

* In your face, Demosthenes!

“Teachers unions fight for fewer students per classroom, and thus more teachers, but typically don’t lobby much for more students (“Make private schools illegal!”?).*”

The teachers’ unions have been the main opponents of voucher initiatives.

That’s like the main thing teachers’ unions lobby for.

A likely immediate effect of adding school vouchers to a district is that a significant number of students would shift to private schools over a short period of time. So that’s one of the factors I was trying to capture with the note about rapidly shrinking markets. The pressure for the auto bailout in the recent financial crisis was a similar thing.

It’s something that offends many people on a values level. The object-level differences between private and public prisons have generally been shown to be fairly minimal.

Private prisons are a small fraction of our total prisons – 6% of state prisoners and 16% of federal prisoners. They spend less on “tough on crime” lobbying than either prison guard unions (who work at both public and private prisons) and police unions. Most of their lobbying money is spent on… getting more contracts awarded for private prisons instead of public ones.

The actual deal with them is that they may be worse than public prisons, and they may be a horrible idea based on moral principles, but they definitely aren’t the cause of our massive incarceration problems. But, there are so many other busted parts of that system (some of whom enjoy popular cultural support) that they’re an easy scape-goat.

It seems like it would be easy to fix the incentives if we wanted to. Private prison gets a flat rate to take care of as many prisoners as the state wants to send them, up to 120% of the current number.

What private prisons do have is an incentive to cut costs. Like, they get rid of the staff psychologist, and send you to solitary when you start raving that the fluorescent lights are talking to you. Or they cut funding for antidepressant meds, and replace your orange clothes with paper coveralls too weak to act as a noose.

I have a problem with it because it sets up an incentive for the private prison industry to, for instance, literally write laws that funnel more people into the prison system.

This Pennysylvania example is one of the most notorious examples, which I believe was also used by TV show Leverage for their private prisons episode.

One case where the private prison was empirically worse than state-run prison.

I was about to link the PA example myself – so I’ll settle for quoting the article for those who don’t feel like following the link:

Two judges, President Judge Mark Ciavarella and Senior Judge Michael Conahan, were convicted of accepting money from Robert Mericle, builder of two private, for-profit youth centers for the detention of juveniles, in return for contracting with the facilities and imposing harsh adjudications on juveniles brought before their courts to increase the number of residents in the centers.

For example, Ciavarella adjudicated children to extended stays in youth centers for offenses as minimal as mocking a principal on Myspace, trespassing in a vacant building, or shoplifting DVDs from Wal-mart.

It takes two to tango. Why is the private prison more blameworthy than the corrupt public officials who accepted the bribe? Strangely, their status as public “servants” did not turn them into angels, yet the main argument against private prisons relies on “public servants” being inherently more moral.

Re: private prisons

In the USA there has been at least one cash for sentencing conviction; a judge in Pennsylvania sentenced juvenile offenders to maximum sentences and they were then sent to various private prisons, who in turn paid the judge for the maximum sentencing.

In the UK, apparently they’ve been in operation since the 1990s. They run under PFI (Private Finance Initiative); the main objection to such Public-Private Partnerships seems to be that the private companies ‘bake in’ compensation clauses in the contracts, such that even if they don’t make the forecast profits/cost cuts, they will still receive the same level of government funding.

It’s hard to know if they’re better or worse; one report said they were better than public service prisons (and that was then criticised for selective use of data), another (issued by the Ministry of Justice) had statistics saying they were worse.

One of the companies (G4S, formed from the merger of Group 4 and Securicor) has since lost its contract to run the first private prison and has not won any other new ones. G4S was also in trouble over its (alleged, pretty shoddy if true) mismanagement of security for the 2012 Olympics in London, for which it won the contract then had to rely on the Army being drafted in to make up for the shortfall when it didn’t recruit enough staff.

Another large company is the French company Sodexo, which I am most familiar with as providing catering services to large organisations. Truly diversification at work, from providing canteen meals to running jails!

The third major group involved in providing private prisons in Britain is Serco, a British outsourcing company which was embroiled in a series of overcharging scandals for the provision of services to various government departments after those services had been privatised, the nastiest of which was probably the allegations of sexual abuse of women detainees at an immigration detention centre it runs.

The major objection to private prisons comes down to the fact that it is in their financial interest to have the maximum number of occupants for the maximum sentence length. You can argue that this takes criminals out of circulation, or you can argue that this pushes for giving people inappropriately long sentences for what are minor offences and works against rehabilitation.

It’s also in the financial interest of the guards’ union for a public one.

Excellent post attacking this oft-repeated claim. A few points:

Which should speak to the definitions of “mentally ill.” As per my recent column:

Features and Bugs

…that fraction is way too high.

Absolutely not. See the work of Amir Sariaslan, particularly his work into neighborhood and poverty effects on mental illness and crime. ALL of that factors you list are FULLY genetically confounded. That is, they are not causal in any way.

Those notwithstanding, you do a good service here, especially by pointing out that most people in prison are there for good reasons. Of course that’s a separate matter from the facts that prisons suck and could use improvement.

I agree that the old mental health facilities are a bit of a nightmare, and community rehabilitation is infinitely better, but this solution still seems a bit unjust. In the US prison is a punishment, and some of the mentally ill criminals can’t be held responsible for their actions. As such, doesn’t it involve punishing the innocent?

For dealing with people who have committed imprisonable crimes as a direct result of mental illness, wouldn’t it be preferable to have completely separate prisons with the same sentence duration, but focussing on positive mental health outcomes rather than punishment?

First of all, I do think that most mentally ill people in prison are there for reasons other than their mental illness – eg the pot dealer with depression. There’s a more philosophical question of whether his depression put him on a life course that led him to selling pot, but now you’re dealing with deep matters of justice and free will, where I think the distinction between mental illness and everything else becomes a little blurry.

There is already a forensic mental health system that deals with, for example, people found not guilty by reason of insanity. I think there are ways to transfer obviously mentally ill people from the normal prison into the forensic mental health system, though I don’t know much about them. I think these serve your role of “completely separate prisons with the same sentence duration, but focusing on positive mental health outcomes rather than punishment”.

Every state is different. There are various options, depending on level of mental illness:

1. Roger has schizophrenia, and likes cocaine. Stan has cocaine. Roger stabs him to death, and takes the cocaine. He goes to prison, because this is illegal (not just the possession of cocaine part; for that you can get a drug program.) The schizophrenia is not a defense; Roger formed the intent to (at least) rob and stab, and that’s murder. In most prison systems, Roger will have some mental health program access, designed primarily to keep him from stabbing other inmates. Participation is non-mandatory, but may generate privileges or earlier possible parole.

2. Pinky has a severe psychotic disorder. She believes that Fonzie is a murderous landshark who must be stopped, and runs him over with her motorcycle. Fonzie dies.

Because she lacks appreciation for her actions, and under her delusional beliefs, she would be innocent of murder, she is found not guilty by reason of insanity. Because of this, she will be housed until she is no longer a danger to the community. Maybe that’s a year from now. Maybe it’s never. And if Fonzie didn’t die… maybe it’s still never. Not guilty by reason of insanity can lead to life sentences for non-life crimes. It can also lead to earlier releases (usually supervised) for very serious crimes.

3. There are special civil commitment laws in many states for mentally disordered offenders and violent sex offenders. You can go to prison, and then get recommitted civilly. This usually has a high standard to require commitment with review periods to ensure the person is still a serious danger.

That’s a quick primer, and doesn’t cover a bunch of other things that happen. It’s also probably different in your state or country. Also, I am more expert than the next guy on this, but maybe not as expert as I ought to be, so could be wrong.

Actually, Pinky would not be found “not guilty”. She knowingly committed assault with a deadly weapon. Her honest belief that the person was not a human being doesn’t change that fact.

If she had been genuinely unaware of her actions–like, she was in a fugue state, or under the influence of amnesiac drugs like Rohypnol or Ambien–then her mental state might be a defense.

Yes, actually, not believing that someone is human is enough to get you off on murder. Or any other crimes that can only be committed against a human.

There was a 19th-century case where a man, his in-laws, and a few others (I believe) were charged with manslaughter instead of murder because the prosecution did not think they could prove beyond a reasonable doubt that they thought the person they killed really was a human being rather than the substitute the — ehem — Fair Folk had put in her place. There was just too much evidence that they were trying to rescue the real woman from the Fair Folk.

Andre Thomas butchered his wife and daughter and I think some in-law (been a while since I read about the case) whilst floridly delusional. Later, in prison, he ate his own eyes-two incidents one separate from the other. Found sane enough to be responsible.

Pinky’s outcome is by no means guaranteed

It’s one thing to be floridly delusional and yet another to have the specific delusion that would mean you would fail of mens rea. If you kidnap a baby under the influence of a delusion, you might be acquitted if you thought the baby was yours, but not if you thought the baby’s mother has stolen your inheritance and you wanted to use the baby as leverage to get it back.

At least in Massachusetts, the forensic hospital is really bad, probably worse than either a normal state hospital or a normal prison. It’s run by the Bureau of Prisons rather than the Department of Mental Health, which gives you an idea.

The courts are set up to avoid the not guilty by reason of insanity plea at all costs. It’s presented to juries as being similar to a not guilty plea (even the wording, it used to be ‘guilty but insane’) and prosecutors will go shopping for expert witnesses who will agree with them when the state doctors make an insanity determination.

I’m not familiar with the subject matter, but I just wanted to say that I really appreciate your concluding statements at the end – its easy to criticize a bad solution, especially in the arena of policy, and much harder to provide a good solution.

Scott, I usually agree with you and enjoy reading your stuff but I have a few nits to pick on this one. Not even sure where to start…

I read the Vox article and I simply didn’t get the same things from it that you did. Nowhere were they suggesting that the mentally ill are more likely to be criminally violent, nor were they suggesting we need to bring back the institutions. What I got from that story was that, *because* there are fewer alternative forms of support, police and the justice system are often the first responders when a problem occurs and family members of a mentally ill person don’t have any other resources to turn to. I’m sure you are aware that tragic shootings have occurred because police were called in to manage what should have been a non-violent encounter, but they were not well equipped to deal with the mentally ill person and somehow things escalated. So the Vox article argues in part that police and correctional officers should have better training to deal with these things.

Also you say: “There’s a six month waiting period for psychiatrists in most parts of the country. The existing mental hospitals – which are different from and often nicer than the old state-run institutions – are constantly turning away people who want to be there because they don’t have enough beds for them. There are a bunch of patients who are having trouble affording their medications. There are special treatment options like day clinics, partial hospital programs, recreational therapy, occupational therapy, et cetera that do really great things but which most patients can’t afford. There are intensive health monitoring programs – think nurses who come to your house and make sure you take your medication on time – which are proven to improve outcomes but which never have enough staff for everybody who needs them. There are omnipresent underfunded community mental health systems. All of these things are doing great work right now. Indeed, the plan for closing the state-run long-term facilities was to gradually transition care to all of these other systems, and where that was supported it worked well, and insofar as it didn’t work well it was because it wasn’t supported.”

This, this right there is what I see as the biggest problem. You’re right that funding was supposed to transfer from the institutions to a more community-based approach to care. But for the most part it didn’t. So you have people who need custodial care who can’t get it. You have family members who are not equipped to deal with a person’s special needs and they are left without many reasonable options. This huge gap in care is what has contributed to more mentally ill on the street, more mentally ill in prison, more mentally ill who are absolutely not getting adequate care and have no place to go.

I think you’re reading a different Vox article than I am. The one I linked to doesn’t mention first responders or police training at all.

Anecdote related to the ineffective survey: I was difficult to handle in grade school, and the school suggested a psychological screening. At the end of the process, I had an autism diagnosis, but early on, I was sent to the school counselor. Among other things, she asked “Do you ever see things that aren’t there?”

I was an imaginative kid, and I could definitely “see” things that weren’t there, if I wanted. So I answered “Yes!”

Cue much panic and handwringing from my parents, teachers, and therapists before the whole thing got resolved.

Hmmm….they seemed to see a mental illness there when there wasn’t one.

Heh. One time after acting out due to frustration with the other monkeys–er, fellow students–my teacher asked me if there was anything wrong with me. I said “well, I’m on drugs”. (My parents had given me an aspirin the previous night.)

I’m sorry I don’t have a citation handy for this but I recently attended a neurogenetics symposium where the keynote speaker was speaking about some of the results of some large population genetics studies.

There were some interesting correlations with professions.

There are genetic variants which are known to be linked to psychosis. They don’t make it certain that you’ll ever suffer from psychosis but they can make it more likely. When looking at the population they found that if you looked at people who had psychosis risk genes but didn’t suffer from psychosis they were significantly more likely to work in creative professions: artists, writers, painters, designers etc.

Speaking as someone who is not formally affiliated with psychiatry in any way… I have no problem with describing the person with auditory hallucinations as “severely mentally ill”. As I see it, although the consequences of her mental illness are not (yet?) significant, the difference between that person and a normally-functioning person is very large, and that by itself justifies the emphatic word “severely”. Similarly, I’d be happy describing someone who’d lost both his legs as “severely handicapped” regardless of whether he felt the absence of legs was an impediment to his lifestyle.

I’ve occasionally (maybe a handful of times a year?) thought I heard someone saying my name when nobody was, in fact, saying my name. For example, when I was a teenager and living with my parents, very occasionally when sitting at a computer doing computer-things I would think I heard my mother calling for me from the other end of the house, go out to see what she wanted, and she wouldn’t have called for me.

I was under the impression that that was a fairly common experience and also not indicative of significant mental health concern, and thought that kind of thing was what Scott was getting at. Maybe I’m wrong?

I tend to agree that that is a common experience and not indicative of significant mental health concern. I didn’t think that’s what Scott was referring to.

I think your reaction to learning that your mother hadn’t in fact called for you was probably something like “oh, I must have made a mistake; I heard something different while I wasn’t paying attention, or there was no such call at all and I merely imagined it” rather than “well, I definitely heard her call; supernatural forces must be at work”. I think hallucinations, if you ask the experiencer about them, provoke the response of “no, the stimulus is, according to my senses as they normally function, really there” rather than “oh, my senses momentarily misfired”.

But I’d be happy to be corrected.

I’ve had aural hallucinations a few times — in the sense of hearing human voices speaking about me, phenomenologically indistinguishable from what I experience when people are actually talking about me, as far as I can tell — and my reaction was basically, hmm, it’s extremely unlikely my parents and friends have gathered together in my neighbour’s flat to badmouth me at the wee hours, it appears I’m hallucinating. These episodes were brought on by stress, sleep deprivation, a rather sudden onset of more severe depression than usual, that sort of thing, and the hallucinations faded away once I got a couple good nights of sleep. I’m pretty sure that if I hadn’t been aware of the phenomenon of “hallucinations in the sane”, I might well have panicked, which in turn could have, for all I know, triggered an actual psychotic episode. As it was, the experience was actually rather interesting — if also somewhat irritating — and to whatever extent I could be said to have been “severely mentally ill” at the time, it has pretty much nothing to do with hearing voices.

When you say “…what Scott is referring to” – I’m referring to a survey that asked prisoners if they ever heard voices.

It sounds like if James had been a prisoner, he would have ticked “yes” to that checkbox and so gotten classified as “severely mentally ill”.

So it’s not really about what I’m referring to, so much as what the survey-taking prisoners thought was being referred to. I’m willing to guess a few of them interpreted the question the same way as James.

Michael, I think you’re conflating hallucinations with delusions.

People do hear voices calling them. I don’t know if that qualifies as “severely mentally ill”.

I often thought I heard my mother or a family member calling my name as a child and teenager, to the point where I’d come into the house/go into the room where they were and ask why they wanted me, to be told “No, I didn’t call you.”

Am I severely mentally ill? I really can’t make a decision on that one at this stage 🙂

Getting Samuel-and-Eli deja vu…

Are amputees who experience phantom limbs “hallucinating”?

Scott’s quest against Vox is starting to feel a bit Quixotic.

Re: poorly performed psychological surveys:

I’m strongly reminded of Richard Feynman’s story, recounted in “Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman,” of how he was originally exempted from the WW2 draft not out of scientific need but for failing the psych exam (http://psychwatch.blogspot.com/2007/09/richard-feynman-gets-psychiatric-exam.html):

““Do you think people talk about you?” he asks, in a low, serious tone.

I light up and say, “Sure! When I go home, my mother often tells me how she was telling her friends about me.” He isn’t listening to the explanation; instead, he’s writing something down on my paper.

Then again, in a low, serious tone, he says, “Do you think people stare at you?”

I’m all ready to say no, when he says, “For instance, do you think any of the boys waiting on the benches are staring at you now?”

While I had been waiting to talk to the psychiatrist, I had noticed there were about twelve guys on the benches waiting for the three psychiatrists, and they’ve got nothing else to look at, so I divide twelve by three–that makes four each–but I’m conservative, so I say, “Yeah, maybe two of them are looking at us.”

He says, “Well just turn around and look”–and he’s not even bothering to look himself!

So I turn around, and sure enough, two guys are looking. So I point to them and I say, “Yeah–there’s that guy, and that guy over there looking at us.” Of course, when I’m turned around and pointing like that, other guys start to look at us, so I say, “Now him, and those two over there‑and now the whole bunch.” He still doesn’t look up to check. He’s busy writing more things on my paper.”

Damn you, you got this one in before I did.

This is exactly the way I’d have answered psych surveys if I hadn’t already read Feynman and other examples of poor superficial evaluations. Almost invariably I asked myself what any psych test or evaluation really meant by any given question before giving an answer.

It makes me wonder what the value is in some tests like the MMPI, where it’s fairly obvious what the question might mean to a psychologists, and that they’re trying to trip you up with some extreme absolutes against innocently moderate questions. At least, it seemed extremely obvious to me at the time–I might not have been the standard from which they were calibrated. I never tried to expressly manipulate the results, mind you, but what they ‘really’ intended by each question was always on my mind.

A lot of things on the MMPI are there to trip you up. They have questions like “I sometimes feel sad” just so that if you say “no”, they know you’re answering the questions in a non-literal way and can adjust for it elsewhere.

Insanity is carrying more about honest answers to arbitrary questions than appearing insane to psychiatrists.

Keep in mind, this was when he was called up to possibly serve in the army.

I’m pretty sure it’s illegal to lie to try to avoid it but answering utterly honestly rather than giving the “right” answers is perfectly legal.

From the rest of the anecdote I didn’t post, it also makes clear that Feynman was (1) really skeptical of psychiatrists, for good reason, and (2) inclined to have fun at their expense. Because, well, it was Feynman. This was the same guy who, at the same age, was giving everyone at Los Alamos heart attacks by cracking open their (poorly made) safes for fun. He was almost certainly giving honest rather than “right” answers to screw with the incompetent army psychs.

Also, it ends with him realizing that he may have gone too far if that psych evaluation affected him at Los Alamos, and wrote back a letter explaining that he believed the psychiatrist was wrong, but was crazy enough to not try to take advantage of it to avoid the draft.

If everyone thought like that there would be a hell of a lot of dishonesty in the world.

Oh wait there is, so people with higher principles are actually considered insane, on a low level.

If there wasn’t people like Feynman in this respect, people like that psychiatrist would ruin everything, but people like that are considered crazy, or failing that, often weird or difficult, for defending a standard we all rely on.

We are so lucky that the appeal of honesty outweighs these considerations in some people.

Being pedantically honest during a psych evaluation is not being more principled than considering what the question is really asking and answering that.

Doc: “Do you ever think people are spying on you?”

Patient thinks: Hmm, maybe this is a good time to make a political point about the NSA… or maybe I can tell that he is trying to discern if I am suffering from some sort of paranoia, and just say nah.

If you can infer the motive for asking a question like, ‘Do you ever think people are spying on you?’, couldn’t a schizophrenic do the same and give the answer that reflects the impression that they want to make rather than their actual thoughts?

Is that rhetorical?

Schizophrenics* who don’t want treatment will do that already. But my impression is that people with strong cases of, say, paranoia will try to convince the doctor that there really are the shadowy conspiracies out to get them. Schizophrenics will likely either want treatment to stop the voices that aren’t real, and answer honestly, or not believe that they hear voices that aren’t “real” and say no, or, possibly, give a self justifying answer about that time everybody else couldn’t hear it but it was real, etc.

Or maybe one is trying to get out of military service by passing as a borderline case by being pedantic. Or trying to get a laugh by pointing out to the administrator that you are smarter than the people who made the test. Not sure those are examples of higher principles.

Feynman’s story was funny, sure, but as a strategy it’s not recommended anymore than this: https://xkcd.com/651/

*May not be clinically accurate descriptions of schizophrenia, but I think the example still stands.

Randy M, I agree. I was just pointing out that that if the person answering the question is competent at inferring the motives of the examiner, the question detects the impression that the person answering the question wants to give instead of detecting whether or not the subject is delusional. Perhaps this is obvious.

That’s why those kind of questionnaires have always seemed useless to me. If you assume that people are answering them in a literal and straightforward way then you get a ton of false positives. But if you assume that people are just inferring whatever answer they’re “supposed” to give and giving that, then the information you’re getting isn’t remotely accurate.

I tend to be skeptical of questionnaires in general for that reason.

First off, of course someone like Feynman could choose to lie, but he’s disinclined to because he’s keeping track of what’s being said, and responding as if we should speak English to each other, rather than go-along-to-get-along -ese. That’s the kind of person he is. Without people who see the importance of truth, or are otherwise against the degradation of “consensus reality”, there’s no force against self indulgence, self interest, narrow mindedness, or any of a million things constantly chipping away at the sanity of, and constricting, “the consensus”.

-It’s not a case of being pedantically honest. It’s a case of being dedicated to the principle of honesty. If that causes you to fail a psych test, the problem is with the psych test, not with a person choosing to simplify their lives by always being literally and directly honest, or choosing not to pander to bullshit of the highest order.

You can consider this a quixotic and ridiculous position on the benefits of literal communication if you’re particulary short sighted, but what it absolutely fucking isn’t, is a mental illness.