I spend so much time arguing with people about the graphics they post on Facebook that I figured I should at least make a blog post out of it so I can pretend it’s productive.

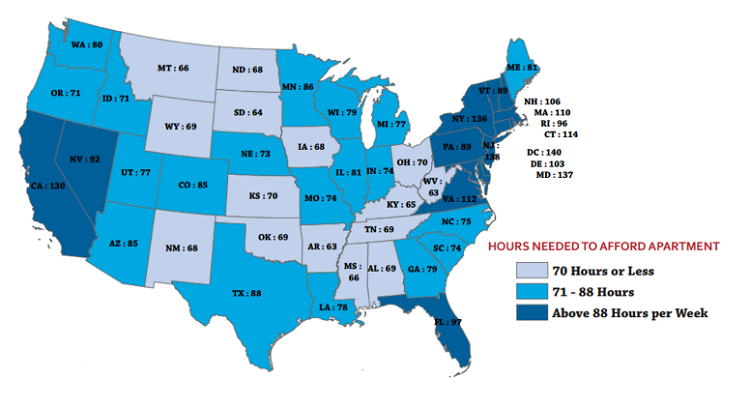

Here’s an image I got from a few places earlier this week. The title was something like “Hours Working Per Week At Minimum Wage Needed To Afford A Two-Bedroom Apartment In Different States”, and it was usually associated with some text about how it was outrageous that the minimum wage isn’t nearly enough to live on:

California might be an unfair example because it’s particularly high. The state I’m visiting right now, Utah, is a bit more representative, at 77 hours/week. But even this requires eleven hours a day, seven days a week. So people’s outrage seems justified.

What’s the catch?

The first catch is that this has nothing to do with the minimum wage. The federal minimum wage sets an effective floor for state minimum wage; many states exceed the federal number but none are allowed to go below it. The states that have the best minimum wage apartment affordability – Arkansas, South Dakota, and West Virginia – all have this minimum permissible minimum wage. On the other hand, the states with the highest minimum wage in the country – Vermont, Washington, and Nevada – have exceptionally poor apartment affordability. I don’t have numbers to put into SPSS, but a very quick eyeballing suggests apartment affordability as measured by this map and minimum wage are actually anti-correlated, probably because high minimum wage implies leftist politics implies dense urban population implies costly housing.

The second catch is related to the first catch: there is no way raising minimum wage could solve this problem. For example, suppose we decided that it was unfair to make people work more than the standard forty hour workweek. What level could we set minimum wage in order to achieve this noble-sounding goal? In California, we would have to multiply the minimum wage by 3.25x, making it $26/hour. I think even most leftists would start to worry that might cause certain problems down the line.

The third and most important catch is that these numbers don’t mean what you think they mean and probably don’t mean anything at all

I first noticed this when I tried to calculate the price of an apartment in California from this data. California minimum wage is $8/hour, so a quick $8/hour * 130 hour weeks needed * 4 weeks/month = average apartment in California costs $4160/month. Renting apartments in California is horrible, but not that horrible.

So I Googled this until I finally found an article in the New York Times where this image had previously appeared, which unlike every instantiation of the image I have seen on Facebook explains the methodology. The numbers are not about how many hours are needed to pay for rent, they’re about how many hours are needed to afford rent, where afford is arbitrarily defined as “be able to pay for rent using no more than 30% of your income”. This brings the cost of a California apartment in the sense everyone is naturally interpreting the picture as meaning back to a slightly-less-unreasonable $1250/month and brings the number of hours per week our hypothetical minimum wage laborer needs to work to pay for rent down to 39 – still worrying, but markedly less so (her Utah counterpart only needs 23.1, which actually sounds doable and liveable).

But we’re still not done here. The graphic specifies that we’re affording a two-bedroom apartment. The best reason to demand a two bedroom apartment is that you are, in fact, two people. Suppose we’re talking about a couple, both of whom earn minimum wage. Now each partner in California only has to work 19.5 hours per week. Each partner in Utah only needs 11.5. This is starting to sound pretty good.

Can we bring these numbers down further? We might note that even if the average California apartment requires 19.5 hours/week, a minimum wage earner might not be going for the average apartment. They might be after something more modest. How much does a modest apartment cost?

I briefly wondered whether the Internet would be able to tell me which Californian county had the exact median land value for California. Then I remembered this is the 21st century and went straight to Wikipedia’s list of California locations by per capita income, which ought to track land value well enough. The exact median is Amador, but since I don’t know where that is I chose Sacramento, which is just next to the median, as my experiment. I asked http://sacramento.apartmenthomeliving.com/ to tell me the rent of two bedroom apartments in Sacramento. Its “sort by price” feature is hopelessly buggy, so I wasn’t able to find an exact median, but I am prepared to believe it is about the $1040 the graphic suggests. And yet it is easy enough to find decent 2 bedroom apartments for as little as $650. If we pretend this case is typical, we can declare that a cheap (but liveable) apartment costs about 62.5% of an average apartment. That means each partner in the Californian couple only has to work 12.2 hours/week, and each partner in Utah only has to work 7.2 hours/week.

In fact, these are still overestimates for a bunch of reasons. Minimum wage earners are probably concentrated disproportionately in poorer areas of a state, so taking the exact median area of a state overestimates the affordability challenges minimum wage earners face. Most couples share a bed, so they’re probably not after a two bedroom apartment and can look for a cheaper one bedroom apartment. And if they really need to, they can do what my roommates do, which is move into a larger house with more rooms and split up the rent even more. In my own living arrangement (two bedroom house where one bedroom is occupied by a couple and the other is occupied by a single person), each partner of the couple only has to work half as hard as the partners in the couple above.

But let’s ignore these additional factors and conclude with our 12.2 number for California. Note that this is less than a tenth of the number on the original graphic, and is probably a heck of a lot closer to what people think when they read what the graphic is trying to do.

I don’t mean to trivialize the problems that minimum wage earners go through trying to pay rent, and certainly not the problems they would go through if they don’t work full-time, or are supporting a non-working family member. It’s just that this image has nothing to do with these problems and its numbers might as well be generated with random dice rolls for all the good they do anyone.

Pingback: Lies, Damned Lies, And Facebook (Part 2 of ∞) | Slate Star Codex

Pingback: Lies, Damned Lies, And Facebook (Part 2 of ∞) « Random Ramblings of Rude Reality

Also, coloured maps like that are always Bad and Wrong, because they arbitrarily give greater emphasis to states which have greater land area. Since states differ hugely in land area and land area is *totally irrelevant* to what we care about here, this is an enormous flaw. A population cartogram is nearly always more appropriate.

Hoo yup. Election result maps mess me up every time, for just this reason. Even when I’ve reminded myself of this problem, there’s a constant creeping unease.

OTOH that error makes the problem seem less than it really is, since it’s mostly low-population cheap states that are inflated.

Great (couple of) posts!

Bunch of flaws with your takedown.

“The best reason to demand a two bedroom apartment is that you are, in fact, two people.”

Or a single parent with a post-toddler child.

“This brings the cost of a California apartment in the sense everyone is naturally interpreting the picture as meaning back to a slightly-less-unreasonable $1250/month and brings the number of hours per week our hypothetical minimum wage laborer needs to work to pay for rent down to 39”

This is missing the point of the 30%, which is that one needs to spend on food and power and (often) car as well as rent. One will need more than those 39 hours to live.

“And yet it is easy enough to find decent 2 bedroom apartments for as little as $650”

Sacramento also has an 11.6% unemployment rate, vs. 6.5% in San Francisco. “Affordable” housing goes in hand with a shortage of even minimum wage jobs.

“In California, we would have to multiply the minimum wage by 3.25x, making it $26/hour. I think even most leftists would start to worry that might cause certain problems down the line.”

OTOH, apparently if the minimum wage had kept up with productivity, it would be about $22/hour. If it had kept up with inflation it would be $10/hour. Australia recently boosted their minimum wage to AUS$16/hour.

On the other hand, part of the reason life on minimum wage sounds nearly impossible (as opposed to merely very difficult) is the hard time achieving 40 hours from just one minimum wage job, which raising the minimum wage would not address.

“Or a single parent with a post-toddler child”

Because it is the role of the government to force all employers to provide people with wages enough to cover their unwise personal choices without consideration of the value the employees provide.

Notice this sentence: “I don’t mean to trivialize the problems that minimum wage earners go through trying to pay rent, and certainly not the problems they would go through if they don’t work full-time, or are supporting a non-working family member.”

My point wasn’t that there aren’t huge problems for poor people, just that this graph doesn’t mean what people think it means. This is also my justification for ignoring the 30% affordability thing – it may be true, but it’s not how the people I saw using this graph interpreted it.

In addition, although a single parent trying to support a child on a single minimum wage job without any overtime is going to have a very hard time, it doesn’t seem obvious to me that this is an argument for raising the minimum wage across the board for everyone, as opposed to some program like government support for struggling single parents.

Speaking as someone who isn’t two people, one-bedroom apartments are only slightly cheaper than two-bedroom apartments, so I think it’s not at all fair to cut the price in half.

This is true, although is there justification for a legal right to be free from the need for rooommates? (ie, get a two bedroom and split it) Because if so college dorms have a lot to answer for.

(No, I don’t think this is optimal, either.)

College dorms have a lot to answer for for a lot of reasons.

Pingback: Linkblogging For 17/04/13 | Sci-Ence! Justice Leak!

Any one who knows anything about housing knows that the standard for measuring affordability is 30 % of income. It has been since the 1970s. Prior to that it was 25%. But even if you didn’t know anything about housing, I would think that one could intuit that your wages are going for more that rent. Seems pretty obvious to ne. I don’t really get the criticism here. (Not to say that every thing that City Lab posts Is gospel.)