San Francisco in the middle sixties was a very special time and place to be a part of. Maybe it meant something. Maybe not, in the long run – but no explanation, no mix of words or music or memories can touch that sense of knowing that you were there and alive in that corner of time and the world….There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning. And that, I think, was the handle—that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil.

— Hunter S. Thompson

Effective altruism is the movement devoted to finding the highest-impact ways to help other people and the world. Philosopher William MacAskill described it as “doing for the pursuit of good what the Scientific Revolution did for the pursuit of truth”. They have an annual global conference to touch base and discuss strategy. This year it was in the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco, and I got a chance to check it out.

.

The lake-fringed monumental neoclassical architecture represents ‘utilitiarian distribution of limited resources’

The official conference theme was “Doing Good Together”. The official conference interaction style was “earnest”. The official conference effectiveness level was “very”. And it was impossible to walk away from some of the talks without being impressed.

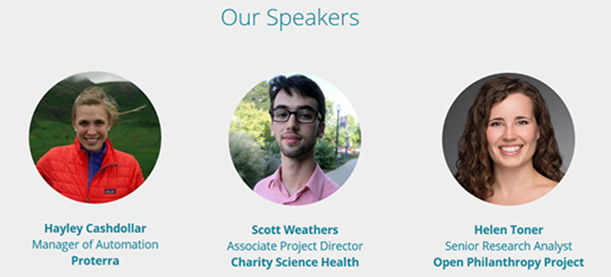

Saturday afternoon there was a talk by some senior research analysts at GiveWell, which researches global development charities. They’ve evaluated dozens of organizations and moved $260 million to the most effective, mostly ones fighting malaria and parasitic infections. Next were other senior research analysts from the Open Philanthropy Project, who have done their own detailed effectiveness investigations and moved about $200 million.

The parade went on. More senior research analysts. More nine-digit sums of money. More organizations, all with names that kind of blended together. The Center for Effective Altruism. The Center For Effective Global Action. Raising For Effective Giving. Effecting Effective Effectiveness. Or maybe not, I think I was hallucinating pretty hard by the end.

.

I figured the speaker named “Cashdollar” was a hallucination, but she’s right there on the website

One of the breakout rooms had all-day career coaching sessions with 80,000 Hours (motto: “You have 80,000 hours in your career. Make the right career choices, and you can help solve the world’s most pressing problems”). A steady stream of confused altruistic college students went in, chatted with a group of coaches, and came out knowing that the latest analyses show that management consulting is a useful path to build charity-leading-relevant skills, but practicing law and donating the money to charity is probably less useful than previously believed. In their inevitable effectiveness self-report, they record having convinced 188 people to change their career plans as of April 2015.

(I had been avoiding the 80,000 Hours people out of embarassment after their career analyses discovered that being a doctor was low-impact, but by bad luck I ended up sharing a ride home with one of them. I sheepishly introduced myself as a doctor, and he said “Oh, so am I!” I felt relieved until he added that he had stopped practicing medicine after he learned how low-impact it was, and gone to work for 80,000 Hours instead.)

The theater hosted a “fireside chat” with Bruce Friedrich, director of the pro-vegetarian Good Food Institute. I’d heard he was a former vice-president of PETA, so I went in with some stereotypes. They were wrong. Friedrich started by admitting that realistically most people are going to keep eating meat, and that yelling at them isn’t a very effective way to help animals. His tactic was to advance research into plant-based and vat-grown meat alternatives, which he predicted would taste identical to regular meat at a fraction of the cost, and which would put all existing factory farms out of business. Afterwards a bunch of us walked to a restaurant a few blocks down the street to taste an Impossible Burger, the vanguard of this brave new meatless future.

.

The people behind this ad are all PETA card-carrying vegetarians. And the future belongs to them, and they know it.

The whole conference was flawlessly managed, from laser-fast registration to polished-sounding speakers to friendly unobtrusive reminders to use the seventeen different apps that would keep track of your conference-related affairs for you. And the of course the venue, which really was amazing.

.

The full-size model of the Apollo 11 lander represents ‘utilitiarian distribution of limited resources’

But walk a little bit outside of the perfectly-scheduled talks, or linger in the common areas a little bit after the colorfully-arranged vegetarian lunches, and you run into the shadow side of all of this, the hidden underbelly of the movement.

William MacAskill wanted a “scientific revolution in doing good”. But the Scientific Revolution progressed from “I wonder why apples fall down” to “huh, every particle is in an infinite number of places simultaneously, and also cats can be dead and alive at the same time”. The effective altruists’ revolution started with “I wonder if some charities work better than others”. But even at this early stage, it’s gotten to some pretty weird places.

I got to talk to some people from Wild Animal Suffering Research. They start with the standard EA animal rights argument – if you think animals have moral relevance, you can save zillions of them for almost no cost. A campaign for cage-free eggs, minimal in the grand scheme of things, got most major corporations to change their policies and gave two hundred million chickens an improved quality of life. But WASR points out that even this isn’t the most neglected cause. There are up to a trillion reptiles, ten quintillion insects, and maybe a sextillion zooplankton. And as nasty as factory farms are, life in the state of nature is nasty, brutish, short, and prone to having parasitic wasps paralyze you so that their larvae can eat your organs from the inside out while you are still alive. WASR researches ways we can alleviate wild animal suffering, from euthanizing elderly elephants (probably not high-impact) to using more humane insecticides (recommended as an ‘interim solution’) to neutralizing predator species in order to relieve the suffering of prey (still has some thorny issues that need to be resolved).

Wild Animal Suffering Research was nowhere near the weirdest people at Effective Altruism Global.

I got to talk to people from the Qualia Research Institute, who point out that everyone else is missing something big: the hedonic treadmill. People have a certain baseline amount of happiness. Fix their problems, and they’ll be happy for a while, then go back to baseline. The only solution is to hack consciousness directly, to figure out what exactly happiness is – unpack what we’re looking for when we describe some mental states as having higher positive valence than others – and then add that on to every other mental state directly. This isn’t quite the dreaded wireheading, the widely-feared technology that will make everyone so doped up on techno-super-heroin (or direct electrical stimulation of the brain’s pleasure centers) that they never do anything else. It’s a rewiring of the brain that creates a “perpetual but varied bliss” that “reengineers the network of transition probabilities between emotions” while retaining the capability to do economically useful work. Partly this last criteria is to prevent society from collapsing, but the ultimate goal is:

…the possibility of a full-fledged qualia economy: when people have spare resources and are interested in new states of consciousness, anyone good at mining the state-space for precious gems will have an economic advantage. In principle the whole economy may eventually be entirely based on exploring the state-space of consciousness and trading information about the most valuable contents discovered doing so.

If you’re wondering whether these people’s research involves taking huge amounts of drugs – well, read their blog. My particular favorites are this essay on psychedelic cryptography ie creating messages that only people on certain drugs can read, and this essay on hyperbolic geometry in DMT experiences.

.

The guy on the right also works for MealSquares, a likely beneficiary of technology that hacks directly into people’s brains and adds artificial positive valence to unpleasant experiences.

The Qualia Research Institute was nowhere near the weirdest people at Effective Altruism Global.

I got to talk to some people researching suffering in fundamental physics. The idea goes like this: the universe is really really big. So if suffering made up an important part of the structure of the universe, this would be so tremendously outrageously unconscionably bad that we can’t even conceive of how bad it could be. So the most important cause might be to worry about whether fundamental physical particles are capable of suffering – and, if so, how to destroy physics. From their writeup:

Speculative scenarios to change the long-run future of physics may dominate any concrete work to affect the welfare of intelligent computations — at least within the fraction of our brain’s moral parliament that cares about fundamental physics. The main value (or disvalue) of intelligence would be to explore physics further and seek out tricks by which its long-term character could be transformed. For instance, if false-vacuum decay did look beneficial with respect to reducing suffering in physics, civilization could wait until its lifetime was almost over anyway (letting those who want to create lots of happy and meaningful intelligent beings run their eudaimonic computations) and then try to ignite a false-vacuum decay for the benefit of the remainder of the universe (assuming this wouldn’t impinge on distant aliens whose time wasn’t yet up). Triggering such a decay might require extremely high-energy collisions — presumably more than a million times those found in current particle accelerators — but it might be possible. On the other hand, such decay may happen on its own within billions of years, suggesting little benefit to starting early relative to the cosmic scales at stake. In any case, I’m not suggesting vacuum decay as the solution — just that there may be many opportunities like it waiting to be found, and that these possibilities may dwarf anything else that happens with intelligent life.

.

This talk was called ‘Christians In Effective Altruism’. It recommended reaching out to churches, because deep down the EA movement and people of faith share the same core charitable values and beliefs.

The thing is, Lovecraft was right. He wrote:

We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

Morality wasn’t supposed to be like this. Most of the effective altruists I met were nonrealist utilitarians. They don’t believe in some objective moral law imposed by an outside Power. They just think that we should pursue our own human-parochial moral values effectively. If there was ever a recipe for a safe and milquetoast ethical system, that should be it. And yet once you start thinking about what morality is – really thinking, the kind where you try to use mathematical models and formal logic – it opens up into these dark eldritch vistas of infinities and contradictions. The effective altruists started out wanting to do good. And they did: whole nine-digit-sums worth of good, spreadsheets full of lives saved and diseases cured and disasters averted. But if you really want to understand what you’re doing – get past the point where you can catch falling apples, to the point where you have a complete theory of gravitation – you end up with something as remote from normal human tenderheartedness as the conference lunches were from normal human food.

.

Born too late to eat meat guilt-free, born too early to get the technology that hacks directly into my brain and adds artificial positive valence to unpleasant experiences.

But I worry I’m painting a misleading picture here. It isn’t that effective altruism is divided into two types of people: the boring effective suits, and the wacky explorers of bizarre ethical theories. I mean, there’s always going to be some division. But by and large these were the same people, or at least you couldn’t predict who was who. They would go up and give a talk about curing river blindness in Nigeria, and then you’d catch them later and learn that they were worried that maybe the most effective thing was preventing synthetic biology from taking over the ecosystem. Or you would hear someone give their screed, think “what a weirdo”, and then learn they were a Harvard professor who served on a bunch of Fortune 500 company boards. Maybe the right analogy would be physics. A lot of physicists work on practical things like solar panels and rechargeable batteries. A tiny minority work on stranger things like wormholes and alternate universes. But it’s not like these are two different factions in physics that hate each other. And every so often a solar panel engineer might look into the math behind alternate universes, or a wormhole theorist might have opinions on battery design. They’re doing really different stuff, but it’s within the same tradition.

The movement’s unofficial leader is William MacAskill. He’s a pretty typical overachiever – became an Oxford philosophy professor at age 28 (!), founded three successful non-profits, and goes around hobnobbing with rich people trying to get them to donate money (he himself has pledged to give away everything he earns above $36,000). I had always assumed he was just a random dignified suit-wearing person who was slightly exasperated at having to put up with the rest of the movement. But I got a chance to talk to him – just for a few minutes, before he had to run off and achieve something – and I was shocked at how much he knew about all the weirdest aspects of the community, and how protective he felt of them. And in his closing speech, he urged the attendees to “keep EA weird”, giving examples of times when seemingly bizarre ideas won out and became accepted by the mainstream.

.

His PowerPoint slide for this topic was this picture of Eliezer Yudkowsky. Really. I’m not joking about this part.

If it were just the senior research analysts at their spreadsheets, we could dismiss them as the usual Ivy League lizard people and move on. If it were just the fringes ranting about cyber-neuro-metaphilosophy, we could dismiss them as loonies and forget about it. And if it were just the two groups, separate and doing their own thing, we could end National Geographic-style, intoning in our best David Attenborough voice that “Effective Altruism truly is a land of contrasts”. But it’s more than that. Some animating spirit gives rise to the whole thing, some unifying aesthetic that can switch to either pole and back again on a whim. After a lot of thought, I have only one guess about what it might be.

I think the effective altruists are genuinely good people.

Over lunch, a friend told me about his meeting with an EA philosopher who hadn’t been able to make it to the conference. This friend had met the philosopher, and as they were walking, the philosopher had stopped to pick up worms writhing on the sidewalk and put them back in the moist dirt.

And this story struck me, because I had taken a walk with one of the speakers earlier, and seen her do the same thing. She had been apologetic, said she knew it was a waste of her time and mine. She’d wondered if it was pathological, whether maybe she needed to be checked for obsessive compulsive disorder. But when I asked her whether she wanted to stop doing it, she’d thought about it a little, and then – finally – saved the worm.

And there was a story about the late great moral philosopher Derek Parfit, himself a member of the effective altruist movement. This is from Larissa MacFarquhar:

As for his various eccentricities, I don’t think they add anything to an understanding of his philosophy, but I find him very moving as a person. When I was interviewing him for the first time, for instance, we were in the middle of a conversation and suddenly he burst into tears. It was completely unexpected, because we were not talking about anything emotional or personal, as I would define those things. I was quite startled, and as he cried I sat there rewinding our conversation in my head, trying to figure out what had upset him. Later, I asked him about it. It turned out that what had made him cry was the idea of suffering. We had been talking about suffering in the abstract. I found that very striking.

Now, I don’t think any professional philosopher is going to make this mistake, but nonprofessionals might think that utilitarianism, for instance (Parfit is a utilitarian), or certain other philosophical ways of think about morality, are quite unemotional, quite calculating, quite cold; and so because as I am writing mostly for nonphilosophers, it seemed like a good corrective to know that for someone like Parfit these issues are extremely emotional, even in the abstract.

The weird thing was that the same thing happened again with a philosophy graduate student whom I was interviewing some months later. Now you’re going to start thinking it’s me, but I was interviewing a philosophy graduate student who, like Parfit, had a very unemotional demeanor; we started talking about suffering in the abstract, and he burst into tears. I don’t quite know what to make of all this but I do think that insofar as one is interested in the relationship of ideas to people who think about them, and not just in the ideas themselves, those small events are moving and important.

I imagine some of those effective altruists, picking up worms, and I can see them here too. I can see them sitting down and crying at the idea of suffering, at allowing it to exist.

Larissa MacFarquhar says she doesn’t know what to make of this. I think I sort of do. I’m not much of an effective altruist – at least, I’ve managed to evade the 80,000 Hours coaches long enough to stay in medicine. But every so often, I can see the world as they have to. Where the very existence of suffering, any suffering at all, is an immense cosmic wrongness, an intolerable gash in the world, distressing and enraging. Where a single human lifetime seems frighteningly inadequate compared to the magnitude of the problem. Where all the normal interpersonal squabbles look trivial in the face of a colossal war against suffering itself, one that requires a soldier’s discipline and a general’s eye for strategy.

All of these Effecting Effective Effectiveness people don’t obsess over efficiency out of bloodlessness. They obsess because the struggle is so desperate, and the resources so few. Their efficiency is military efficiency. Their cooperation is military discipline. Their unity is the unity of people facing a common enemy. And they are winning. Very slowly, WWI trench-warfare-style. But they really are.

.

And I write this partly because…well, it hasn’t been a great couple of weeks. The culture wars are reaching a fever pitch, protesters are getting run over by neo-Nazis, North Korea is threatening nuclear catastrophe. The world is a shitshow, nobody’s going to argue with that – and the people who are supposed to be leading us and telling us what to do are just about the shittiest of all.

And this is usually a pretty cynical blog. I’m cynical about academia and I’m cynical about medicine and goodness knows I’m cynical about politics. But Byron wrote:

I have not loved the world, nor the world me

But let us part fair foes; I do believe,

Though I have found them not, that there may be

Words which are things,—hopes which will not deceive,

And virtues which are merciful, nor weave

Snares for the failing: I would also deem

O’er others’ griefs that some sincerely grieve;

That two, or one, are almost what they seem,

That goodness is no name, and happiness no dream.

This seems like a good time to remember that there are some really good people. And who knows? Maybe they’ll win.

And one more story.

I got in a chat with one of the volunteers running the conference, and told him pretty much what I’ve said here: the effective altruists seemed like great people, and I felt kind of guilty for not doing more.

He responded with the official party line, the one I’ve so egregiously failed to push in this blog post. That effective altruism is a movement of ordinary people. That its yoke is mild and it accepts everyone. That not everyone has to be a vegan or a career researcher. That a commitment could be something more like just giving a couple of dollars to an effective-seeming charity, or taking the Giving What We Can pledge, or signing up for the online newsletter, or just going to an local effective altruism meetup group and contributing to discussions.

And I said yeah, but still, everyone here seems so committed to being a good person – and then here’s me, constantly looking over my shoulder to stay one step ahead of the 80,000 Hours coaching team, so I can stay in my low-impact career that I happen to like.

And he said – no, absolutely, stay in your career right now. In fact, his philosophy was that you should do exactly what you feel like all the time, and not worry about altruism at all, because eventually you’ll work through your own problems, and figure yourself out, and then you’ll just naturally become an effective altruist.

And I tried to convince him that no, people weren’t actually like that, practically nobody was like that, maybe he was like that but if so he might be the only person like that in the entire world. That there were billions of humans who just started selfish, and stayed selfish, and never declared total war against suffering itself at all.

And he didn’t believe me, and we argued about it for ten minutes, and then we had to stop because we were missing the “Developing Intuition For The Importance Of Causes” workshop.

Rationality means believing what is true, not what makes you feel good. But the world has been really shitty this week, so I am going to give myself a one-time exemption. I am going to believe that convention volunteer’s theory of humanity. Credo quia absurdum; certum est, quia impossibile. Everyone everywhere is just working through their problems. Once we figure ourselves out, we’ll all become bodhisattvas and/or senior research analysts.